Stephen Reustle uses a “wine thief” to extract wine from a barrel in the cellar of his Prayer Rock Winery.

By Marisa D’Vari

Tempranillo’s tale begins during the Middle Ages, a turbulent yet transformational period for Spanish viticulture. As the Moors retreated south, the Christian reconquest brought a resurgence of wine production across the Iberian Peninsula. In the wake of Islam’s retreat, people could enjoy drinking again. Historians speculate that the Tempranillo grape was cultivated by monastic orders, who played a crucial role in vine propagation and production during this time.

Tempranillo’s name translates as “early one.” The fact it ripened so quickly made the grape a favorite of vineyard planters. Tempranillo soon spread across 60 regions of northern and central Spain with each area giving the grape a local name. The two areas where its roots went deepest were Rioja and Ribera del Duero.

Rioja Leads the Way

Rioja established the “traditional” style of a Tempranillo-based wine, which usually is blended with Garnacha, Mazuelo, and Graciano grapes before spending years aging in American oak.

Rioja was also the first Spanish region to obtain Denominación de Origen Calificada (DOCa) status in 1988. Its classification system consists of four categories: Rioja, Crianza, Reserva, and Gran Reserva. The categories represent the amount of time the wine spends in oak.

Ribera del Duero: Spain’s Rising Star

A few hundred miles west of the Rioja region\ lies the dynamic and rapidly emerging wine region of Ribera del Duero. This region, which obtained Denominación de Origen (DO) status in 1982, has quickly risen to prominence, with its Tempranillo wines (locally known as Tinto Fino) rivaling those of its more established neighbor Rioja.

Like Rioja, Ribera del Duero also has a wine classification system based on years spent in oak, albeit a simpler one. Here, Tempranillo is often vinified alone, showcasing the grape’s full potential. However, small amounts of other grapes like Garnacha and Cabernet Sauvignon can be used for blending.

Despite both producing excellent Tempranillo wine, the wines of Rioja and Ribera del Duero present distinct expressions of this versatile variety.

Influenced by the region’s diverse terroir and the use of American oak, Rioja wines present a balance of fruit and spice, with notes of vanilla and sweet cherries. The wines of Ribera del Duero, grown at higher altitudes and in a harsher climate, tend to be more powerful and concentrated. These wines, often aged in French oak, present robust tannins with darker fruit flavors and a minerality that reflects the region’s limestone-rich soils.

Tempranillo in America

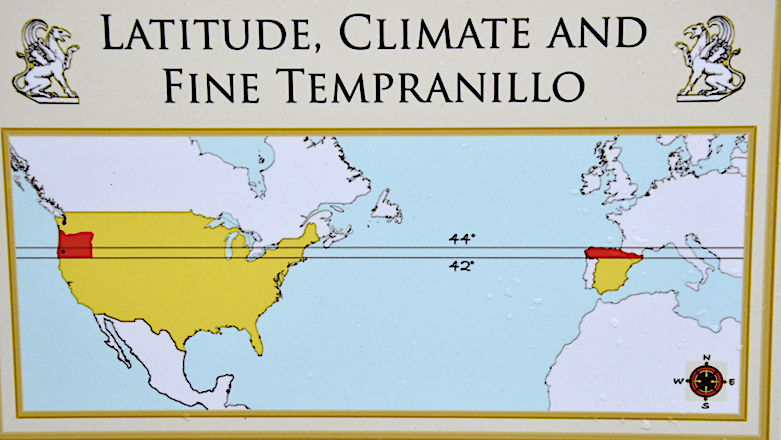

This graphic on the wall of Abacela’s Tasting Room pays homage to Spain and the Northern Hemisphere latitude where Tempranillo grapes grow best. Photo by David DeVoss

Until recently, American producers focused their energies on more easily recognizable international grape varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon or Merlot Grapes that were easy to market. But over the last decades, some passionate producers in Oregon and Texas have developed a fascination for Tempranillo, going to extraordinary lengths to give it a good home.

Oregon: Where It All (Mostly) Began

Physician Earl Jones pioneered the cultivation of the Tempranillo grape in America. Why? Because the wine made from Tempranillo grapes was delicious and affordable. But first, he had to find the perfect terroir and temperature to suit the grape.

Jones needed climate data, so he began studying weather records from as early as 1931. He compiled a list of promising locales and then, like Goldilocks testing porridge, began the process of elimination: too hot, too wet, too expensive.

This intensive research took him years, but ultimately led him to the Umpqua Valley is Southern Oregon where he purchased 500 acres of barren land, that seemed perfect for his early ripening varietal. Yet when Jones’ elderly father saw the land, all the older man could say was: “Son, you lost you’ve mind.”

“The reason for my grandfather’s reaction is that he farmed vegetables in western Kentucky so, from his experience, relatively flat land was ideal for farming,” explains Earl’s son Greg. “He simply did not have the perspective of how beneficial being on sloped land was to grape growing.”

Earl Jones likes to stop by a mileage post by the side of his vineyard and ponder Temprenillo’s migration from Spain to Oregon. Photo by David DeVoss

Jones, his wife Hilda and their son Greg persevered. In 1995 they founded Abacela winery and planted 76 acres of Tempranillo. They raised hay on another parcel which they traded to a local Wildlife Safari park for elephant dung they used to fertilize the vineyard.

A Tempranillo Pioneer

Two years after his first commercial planting Jones took his Tempranillo to the Oregon State Fair and earned several medals. Within weeks Abacela Tempranillo became a cult sensation at restaurants in Portland, the state capital.

As demand for Jones’ Tempranillo grew so did its reputation. At the San Francisco International Wine Competition, judges awarded him their wine Double Gold Medal and first place. In 2009, Abacela Tempranillo became the first American wine to win Spain’s Medalla de Oro.

Today, the family’s once-barren land showcases several beautiful vineyards, an elegant hospitality center offering food and wine pairings and a wine cellar designed for private dinners. Greg Jones leads tours (limited to four people) of the property that include a wine tasting within the vines and a charcuterie plate back at the Vine & Wine Center.

And if that doesn’t fill your day you always can take a jeep tour of the nearby Wildlife Safari Park, which maintains its business relationship with Abacela, or drive south to Ashland (pop. 21,400), home of Oregon’s summer Shakespeare Festival.

Abacela Winery founder Earl Jones and his son Greg, Abacela’s current CEO, inspect their vineyard. Photo by Andrea Johnson

Prayer Rock Vineyard

While Earl Jones was building Abacela, another Tempranillo aficionado named Stephen Reustle was planning to launch a wine empire of his own. Reustle did not know Jones or his Umpqua-based winery. But he shared a love of Tempranillo’s taste, quality and low production costs.

After selling his East Coast marketing company, his search for land suited to grow Tempranillo took him to California’s Sonoma County and to the Temecula Valley further south.

But the price of land, California’s ever-increasing taxes and bureaucratic regulations forced him to look North. “In Oregon, there is no sales tax, real estate taxes are less, as well as incidental taxes such as auto registration,” he says. “The County governments were very welcoming in Oregon, whereas California was highly regulatory and not interested in additional vineyards. Access to water and a dependable labor force was much better in Oregon.”

Though not a winemaker, Reustle was a fast learner. He went to the University of California’s Davis campus and asked oenology professors what books to buy. Study and research brought him to Southern Oregon. Once he bought land, he walked into the Abacela wine cellar and offered Earl Jones “free help” in exchange for tips on grape growing and winemaking.

Jones accepted the offer, mentored Reustle, and helped him start Prayer Rock Vineyards. Today both vineyards are Tempranillo powerhouses. Recently, Prayer Rock won “Best of Show” for its white wine at the San Francisco International Wine Competition.

Disasters and Successes

If you visit Prayer Rock Winery you’ll see a gorgeous estate equal with the best in California’s Napa Valley. You might imagine Reustle’s journey from planting the vines to collecting the wine fair trophies was uneventful.

Stephen Reustle takes visitors on a tour of Prayer Rock Vineyard

But Reustle had many close calls that could have killed his dreams. In the early days, he didn’t know that in Oregon rain falls mainly in autumn, and when it rains, it rains hard. When the atmospheric pressure began Reustle’s vineyard was in danger of washing away. Fortunately, a neighbor loaned him a tractor along with a device for seeding grass, allowing Reustle to stabilize his slope before the heavy rains began to fall.

Reustle soon realized that in the Umpqua Valley, neighbors relied on one another. When asked if there was any jealousy or resentment about growing an “unusual” grape variety, he responded that all the wineries have a vested interest in seeing other Oregon wineries succeed.

Tempranillo in Texas

Southern Oregon and Texas’ Hill Country are diverse in topography and climate, yet Tempranillo grows successfully in both. Julie Kuhlken grew up in the Texas Hill Country, part if a family growing the popular international grapes of the time – Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Chardonnay. Like Earl Jones, she became obsessed with Tempranillo, believing that an “early ripening” grape could stand up to the challenging Texas climate.

To prove her theory, she started Pedernales Cellars in Stonewall, TX where today she is the chief executive officer. Located west of Texas’s state capital in Austin close to the Lyndon B. Johnson National Historical Park and the picturesque communities of Fredericksburg and Lukenbach, the vineyard has prospered despite sudden rainstorms and temperature swings.

Pedernales Cellars Tasting Room is famous for its Tempranillo.

What’s most curious about Kuhlken’s approach to her Tempranillo, which comprises 50% of her production, is that she follows the mandates of the classification system in Rioja, Spain. This means that while she does not have this classification on the label, she internally ranks her Tempranillo wines as “Joven” (meaning young and unoaked), Crianza (aged for two years in wood), and Riserva (more than three years of barrel age and one year in bottle).

“Adhering to the regulations of where the grape naturally grows is important to me,” she says, adding that she and her staff often taste test their wine against wines from Spain and other US Tempranillo producers. She explains that in San Antonio, her winery takes part in a fair called Texas Two Sip in which producers bring bottles of their Texas-produced wine to compete against traditional wines from their “Old World” counterparts.

“When people first started coming to the tasting room,” she says, “people couldn’t pronounce the grape name Tempranillo and had no idea what ‘joven’ meant. Now Tempranillo is one of the most popular grape varieties in Texas and people can’t get enough of it.

Saludos a Todos

With its ability to thrive in varying climates, the tale of Tempranillo is an intriguing saga of adaptation and survival that today is being told in the vineyards of Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Australia and Washington’s Yakima Valley. When Stephen Rustle went searching for a suitable location for his Tempranillo vineyard twenty years ago, he found Oregon’s Willamette Valley too cold. Perhaps today, Tempranillo the “early ripening grape” might be just right.![]()

Marisa D’Vari is a travel and wine writer who writes for several international and domestic magazines. You can discover more at her website TheLuxuryReport.com