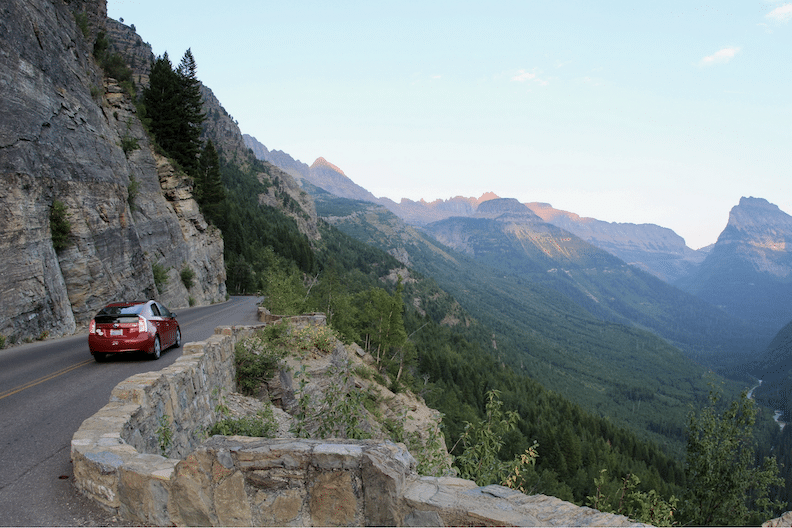

An open road through the mountains evokes the beauty, promise and freedom America offers to all its citizens.

By Mark Orwoll

The summer of 2021 is full of hope and promise. If vaccinations proceed apace, it will be the season to celebrate our first breath of freedom in more than a year. Freedom from our homebound lives. Freedom from kitchen-table schoolrooms. Freedom from cultural incarceration. And, yes, freedom from Zoom.

As Americans begin to crawl out of their wintry caves they want to do one thing more than any other. They want to go. Go visit relatives who have been little more than disembodied voices for the past 12 months. Go camping at a national park. Go visit former colleagues who now work remotely from exotic locales. Go anywhere. Just…go!

Travel experts are predicting a surge in driving vacations this summer because of that overused, but still accurate phrase, “pent-up demand for travel.” Americans are thinking about road trips of the past and dreaming about the vastness of America still waiting to be explored. The magnificent deserts of the Southwest filled with saguaro and sage. The stirring mountain ranges further north, where chichi ski villages peacefully coexist alongside beer-drinking cattle towns. And rural Main Streets lined with Victorian storefronts, where banners in front of town hall remind passersby of the upcoming Lion’s Club picnic.

Yes, everyone is ready to go. I’m ready to go. Which got me thinking about not just where I want to go next, but where I went in years gone by and what America is like now. In the past year, perhaps more than at any other time in recent memory, our neighborhoods, our towns, even our families have been divided. Red and blue. Rich and poor. Rural and urban. Liberal and conservative. That division may be a large part of what makes us want to hit the road so desperately—just to get away from all that.

America is fractionalized in so many ways. But it always has been. When I made my first cross-country road trip, one of the great divides was the generation gap. The term now sounds quaint. But the gulf between the old and the young was all too real for those of us who lived through it.

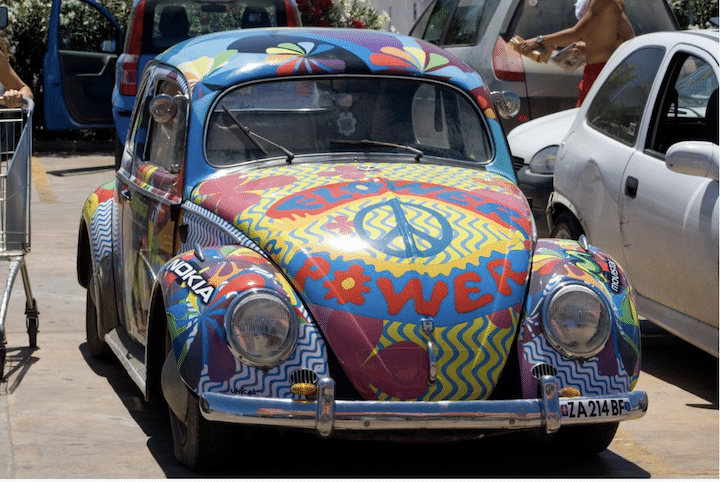

A marvelous example of German engineering, the Volkswagen Beetle may not be the best vehicle to take on a cross country trip. Photo by Mathias Degen

The Interstate

The year was 1972. I was 18, and so was Gary Jaycox, my high school buddy and soon-to-be road-trip sidekick. We had concocted the idea of an ocean-to-ocean trek in the waning months of our senior year. It would be so cool. A couple of Southern California kids on the highway to adventure! We’d meet girls! We’d visit states that allowed 18-year-olds to drink legally! We’d make it all the way to New York City and maybe meet John Lennon strolling with Yoko in Central Park!

We decided to drive my 12-year-old Volkswagen Beetle, which had a fair-to-middling chance of making it there and back. When I told my father about our plans, he looked horrified. I’m sure he was visualizing that VW Bug. The bumper sticker with a picture of the Zig-Zag man and a Grateful Dead concert handbill in the window. The missing back seat transformed into a woo grotto with avocado-green shag carpeting and colorful lounging cushions. Irrespective of the telltale stems and seeds on the floor, the funk-mobile gave every appearance of being a rolling opium den.

Within 24 hours of telling him our big travel news, my dad somberly informed me that we could take his new Datsun pick-up truck instead. He would use my Vee-dub to commute to his job at the Lynwood Unified School District. He’s gone now, my generous, conservative dad, but I still think of him pulling into the district headquarters every morning that summer, looking as if he’d just returned from a Griffith Park love-in.

The trip went smoothly as we traveled east on Route 66 through the red-rock country of Arizona. New Mexico struck us as a Carlos Castaneda fever-scape come to life. In the eastern half of the country, we usually stayed on the interstates, our desire to make better time leading us to take roads like I-44 to St. Louis, where we marveled at the Gateway Arch. Most nights we pitched a tent in the nearest KOA campground. Once, somewhere between Cincinnati and Columbus, Ohio, off I-75, we coasted into the facility after dark with headlights off so we didn’t have to pay the camping fee. But in between east and west was Texas…

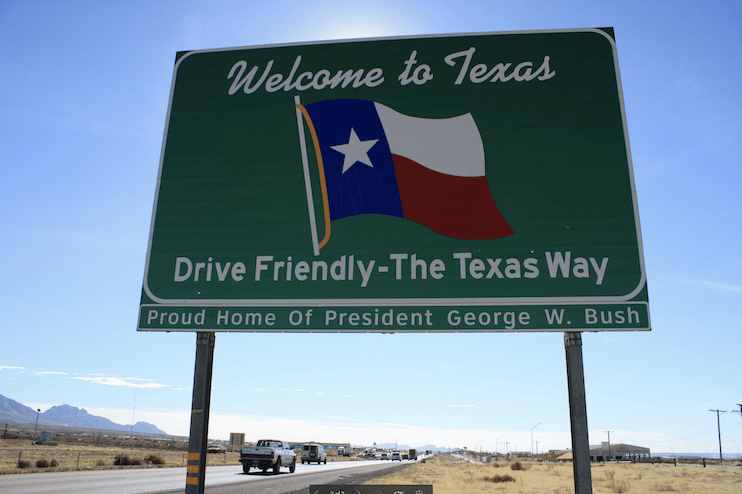

Texas is a welcoming, hospitable state full of friendly people. Just ask the thousands of Californians presently moving there, along with many of Silicon Valley’s leading tech companies.

Texas was our big fear. Texas, where, we were certain, F-150 cowboys with rear-window rifle racks would as soon shoot you as look at you. So we devised a route following I-40 that would take us through just a smidge of the state’s northwestern corner. We filled the gas tank in Tucumcari, New Mexico, then sped through the arid landscape, our ponytails tucked under our shirt collars.

The landscape along I-40 seemed as bleak and hopeless as America itself at the time. Besides the generation gap, the ongoing Vietnam War was fragmenting the nation. I had just received number 56 in the draft lottery. Considering that the previous year’s draft conscripted young men through number 95, it looked like this stoner was going to Nam. The Attica Prison riot, the Knapp Commission on police corruption in New York City and the untimely death of singer Jim Morrison were fresh in everyone’s mind. The President of the United States was at that very moment attempting to stop the FBI from investigating the White House-approved Watergate break-in.

Four hours and 256 miles later, we coasted on fumes into Elk City, Oklahoma, and let out a sigh of relief.

No Texas Rangers threatened us. No right-wing roughnecks flipped off our California plates. In fact, it wasn’t until we arrived a week later in sophisticated, liberal Manhattan that a dude named Troy invited us to a party with lots of girls and beer, then robbed us in the stairwell of an abandoned East Village tenement.

The episode wasn’t a disaster. No one got hurt. We left our traveler’s checks back at the 23rd Street YMCA. And we could now say we had street smarts.

The interstate highway system was created to transport military equipment quickly and efficiently, but it’s the antithesis of human communication or meaningful learning. More than anything, the trip taught me two things: to make good time, take the interstate; to get good insights, take the back roads. It was on these narrower roads and byways that I fully realized the eye-meltingly gorgeous and productive landscape of America. Deserts in the Southwest. Rolling hills and cornfields in the Midwest. Lush hardwood forests in the East and Upper Midwest. And the Rocky Mountains…

The Lonely Mountain Road

I maintained a fascination for the Rocky Mountains that eventually resulted in an intriguing magazine assignment. I concocted a route that would lead from Canada to Mexico along a series of roads that would parallel, as closely as possible, the Continental Divide. I say “a series of roads,” but I still think of that trip as being on a single road, a tarmacadam Frankenstein stitched together and come to life. From Glacier (National Park) to Gila. From Labatt’s to Dos Equis. From “eh, you know” to quién sabe?

How to explain the appeal of certain set distances–distances whose mileage is less important than their very concept, whose allure (whose myth!) is so powerful that their names have entered our daily vocabulary. Cross-country. Transatlantic. Cape-to-Cairo. Even around-the-world. How to explain it, except to say their common thread is what matters is not the arrival, but the journey.

Of them all, the one that has tugged strongest at something fundamental in me is the Continental Divide. The Divide, of course, is that imaginary line through the peaks that separates water flowing to the Pacific from water flowing to the Gulf. It also is a cultural divide separating the rough-and-ready West from the staid Midwest and the effete East—or, at least, many people like to think so.

The glacier-lined Going-to-the-Sun-Road begins on the Canadian border and heads south to warmer climes.

The journey began on the glacier-lined Going-to-the-Sun Road at the Canadian border. From there I made my way south, keeping as close as possible to the Divide. An eagle flew past my windshield on the Pintler Scenic Highway southeast of Missoula. I stood alone at the isolated grave of Sacagawea in Wyoming’s mountainous Wind River Reservation at dusk during a thunderstorm. Driving south on Route 24 from Buena Vista, Colorado, I admired the wall of Fourteeners to the west–some of the greatest mountains in America, named for the nation’s greatest universities: Mount Harvard (14,420 feet), Mount Yale (14,196 feet), Mount Princeton (14,197 feet). Despite being a Californian, I took pride in these Colorado mountains–as an American.

Not to minimize the natural attractions of such a road trip, but it’s the human side of the drive that lives even stronger in memory. Boiled down, what that mountain road drove home to me was the willingness, the eagerness even, of Americans to share experiences with strangers.

Wyoming Highway 28 passes mainly through brown and dreary high desert, at one point relieved by a handsome granite monument erected in 1956 and commemorating the Parting of the Ways–a split in the old Oregon Trail where groups of pioneers bound for California went one way and those headed for Oregon went another. But 30 years after erecting the memorial, some researchers discovered that the Parting of the Ways was actually situated some 10 miles west. Historians had been misled by a wagon trail, its ruts still visible, that had been used by miners going south to the Union Pacific rail line, long after the heyday of the Oregon Trail. To correct the mistake, a second (and appropriately contrite) historical marker was erected next to the first to acknowledge the error. There I met an elderly woman who had turned off the highway to read the markers. She was on her way to a gemology show in Riverton.

In Wyoming the old Oregon Trail splits with one fork heading straight while the other veers south to California. Photo by Bob Wick: Bureau of Land Management

“I always stop at these monuments,” she said.

“You’re a history buff?” I asked.

“No, but I’m old,” she said. “I get stiff, and there’s always room on the highway to park your car at these markers so I can stop and stretch.”

Then she laughed so hard I had to laugh with her.

The Divide is like the Four Corners–everyone wants to say they were in four places at once, or, in this case, two–one foot in the east and one in the west. US-20 south of Yellowstone crosses the Divide at an elevation of 8,262 feet, with a pull-off for picture-takers. A man and woman from Texas (from Texas!) happily took my photo standing astride the Divide, and I reciprocated.

“We drove clean past it,” the woman said. “We had to drive five miles to find a place to turn around so we could come back here!”

Continental Divide in Yellowstone. Photo by Malcolm Manners, Flickr

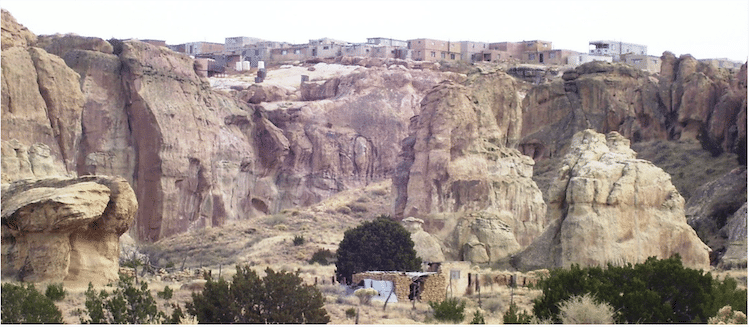

Acoma Pueblo, called Sky City, is an ancient and hauntingly beautiful Native American village on top of a mesa on Indian Service Route 38 west of Albuquerque. A middle-aged man named Randy caught my attention and pointed to a flat 40-foot-long rock slanted at a 45-degree angle.

“We used to slide down that thing when we were kids,” he recalled. “This was our playground. I wore out quite a few pairs of pants on it.”

He had since moved with his wife and three children to one of the towns in the valley. The sky was a heavy gray, dampening the sound so that the entire valley surrounding the mesa was quiet. I asked Randy if he’d prefer to live up on the mesa again.

“The people in Sky City don’t have electricity,” he said, “and they still use cisterns. I’m kind of used to my running water and cable TV.”

As I continued through New Mexico, crossing the Continental Divide at 6,559 feet in the Gila Mountains, I glanced at the sky, where a strange meteorological occurrence was underway. The clouds were a mix of cumulus and stratus, and at one celestial juncture, there was a gap into the pale-blue sky beyond. The clouds that formed the opening to the sky were multicolored–pale yellow, pink, light orange, almost like a sunset, but it wasn’t yet quite noon. I nearly drove off the road twice trying to get a look at it so I stopped at a broken-down trading post and pointed out the phenomenon to two old-timers sitting out front.

“What the hell is it?” said one, squinting curiously above us.

“I imagine it’s a reflection of water vapor,” said the other. “Looks kind of like a rainbow…but that’s a damn strange rainbow.” Then turning to me, he said, “There’s coffee inside.”

New Mexico’s Acoma Pueblo often is called “Sky City.” Photo by Beyond My Ken

The Shunpike

And that’s the thing about road trips in America: Everyone wants to talk! This delightful and curious fact was driven home while I spent a couple of weeks prowling the backroads of Northern California.

An express-mail deliveryman was having lunch at Joselina’s Mexican Restaurant in Susanville when I took the table across from him. I was driving across the remote Trinity Alps and the state’s little-known northeastern corner.

In the friendly custom of these rural parts, the man asked me where I was from. On learning that I had just driven into town from the airport in Reno and that I was on my way north to the ranching community of Alturas, he proceeded to orient me from across the vastness of a drippy cheese enchilada.

“See that desert?”

He looked out the window onto Main Street. All I could see was a convenience store and some passing cars, but I knew what he meant. On my drive up from Reno, the desert had been alongside the road most of the way, giving ground to farms and ranches only as I neared Susanville.

“Straight out that way’s Reno,” he went on. “Keep on going and there’s Salt Lake City. Go about two hundred miles or so northeast of here and you hit Idaho. It’s all desert. Go south and that desert runs all the way down through Arizona to Mexico. Desert’s probably killed more people than snow in the passes. All’s I’m saying is watch out for the desert, ’cause it’ll kill ya.”

What is it about Americans, especially in out-of-the-way cafés, isolated roadhouses, and remote retreats, that makes them want to warn others? Kindness? A sense of superiority (as in, I know something you don’t)? Liability concerns?

Downtown Susanville, the county seat of Lassen County, California Photo by Shakata Ga Naijpg

Fifty miles up Highway 395 from Susanville is Spanish Springs Ranch, a former cattle spread and dude ranch that recently closed. When I visited it was a going concern, with trail rides, trap shooting and dozens of activities spread across 3,500 acres filled with sagebrush and juniper. I’d just entered the ranch’s cookhouse on my first day of my visit when the restaurant manager offered me a vague warning.

“This is a dude ranch,” he began, “but it’s not Disney World. We’ve lost guests before,” he scowled. “Doctors and lawyers come up here to get away from the city. They jump on a horse and get carried away. I tell ’em, not to get lost. We’ve got bears and bobcats. This is real life out here. We’ve had to get up search parties and track down a few guests. This place is still wild.”

The next morning, I decided to go in search of a ghost town called Hayden Hill. On the way, I stopped at a second-hand shop in a barn on Main Street in Adin. The owner wore a baseball cap and a long beard, with a belly that hung down over the front of his trousers. He was very friendly—most Americans are friendly–and wanted to talk.

“They’re thinking of reopening the mines up at Hayden Hill,” he told me when I mentioned my destination. “Say there’s still gold there. I know a lot of people around here’ll be glad of it. They could use the work since the lumber mill closed up. ’Course, they got the environmentalists up there poking around the old buildings, so who knows? They might find some endangered species of rock and stop the mines from opening.”

I heard the warning coming a mile away.

“I’d be careful up there,” he cautioned. “People go up there, poke around the mines, and don’t come back.”

The “environmentalists” at Hayden Hill, which today is closed to the public, turned out to be a group of archaeologists from Reno who were collecting relics for display in a museum. Two young women on the research team saw my car pull up and walked over.

They were young, pretty and suspicious. I told them I was just passing through and had an interest in history. From where we stood, I could see two miner’s cabins, a dilapidated sluice box and huge piles of rubble that must at one time have been buildings. Not much to collect or exhibit, I thought.

As the women turned back to rejoin their research, one of them looked over her shoulder and warned me to watch where I walked. “There are a lot of mine shafts around here,” she said, “and they’re not all marked. Don’t stand on any piles of rocks, ’cause that’s how some of them are closed up, and you might fall through.”

Founded in 1850, Weaverville, is a California Gold Rush town that today is the county seat of Trinity County. The population of 3,600 loves to gether in the town’s historic dictrict for parades or other community events. Photo by Almonroth.

East-West Highway 299 across California’s northern edge passes through some of the state’s most arresting mountainous countryside and charming small towns, especially Weaverville, in the heart of the Trinity Alps. But it was in Weaverville that I received some of my most unnerving warnings—and not about abandoned mine shafts.

“Do not go to Denny,” said a waitress when I mentioned the small mountain outpost. “Nuh-uh. The pot-growers are liable to shoot you.”

A resort owner spoke to me like a veteran chief petty officer advising a fresh-faced sailor ready for his first shore leave: “Steer clear of Hayfork. I’m serious. Not even the IRS goes there without a convoy of sheriffs.”

“There are some crazy, mean people living back in these mountains,” a man named Bob, from nearby Lewiston, told me within two minutes of meeting me. He spoke as if he made a living from warning people. “If they shot you and threw you down a mine shaft, nobody’d ever find you.”

When you follow the shunpike, you can’t say nobody warned you.

Main Street

Warnings have their place, especially if they’re well meant. But more useful are kindnesses rendered when you’re in distress. And there’s often no better place to find such generosity than Main Street. It could be Main Street in Hailey, Idaho, or Enterprise, Mississippi, or anywhere in between. It doesn’t even need to be called Main Street. In my case, it was North Walnut Street, Avoca, Iowa, population 1,413.

My nascent journalism career in Manhattan had stalled, and I’d just been accepted to grad school in San Francisco. So while my wife remained briefly in New York to tie up loose ends I decided to drive across the country to get us settled.

My car at the time was a brown Ford Granada, perhaps the least snazzy automobile ever to roll off a Detroit assembly line. I packed only a few suitcases and a birdcage holding our pet parakeet, Critter. Things started off smoothly. But going up those steep grades in central Pennsylvania strained my transmission so that it continually slipped out of gear and made strange noises from somewhere below my feet. For the next thousand miles, my stomach was as tight as the transmission bands were loose.

“I may be able to drive across the Midwest like this,” I thought, “but I’ll never make it over the Rockies.”

I didn’t even get a chance to try. Ninety miles west of Des Moines, as I was puttering along in the slow lane of I-80 the transmission cut out again. And suddenly I found myself on the outskirts of Avoca.

North Elm Street runs through the heart of Avoca Iowa Photo by Jared Winkler

I managed to pull over to the side of the street and retrieved Critter from the backseat. Together we walked down the road past a cemetery toward what looked like a diner. I wasn’t my best as I entered the diner, unshaven for three days, wearing the same clothes in which I had left New York and holding a cage with a parakeet squawking, “I love you. I love you. I love you.” I took a seat at the counter before anyone could block my entrance or call the police, placing Critter at my feet.

A waitress came right over to me like she had been waiting for me to arrive. “I heard your bird,” she said. “I had a parakeet. Never could teach it to talk.”

As she spoke, she placed a coffee cup in front of me without asking and poured it full. “Now, I have to say, though, that most people don’t take their parakeets for walks. That must be something new because I never heard of it.”

I explained that my car broke down, how I was supposed to be in San Francisco in time for classes in a week, how I wasn’t exactly sure what was wrong with my car or how expensive it would be to fix or where I would sleep that night and by the way where the heck am I? Oh, I was at my best that day. Stellar.

She dropped her smile and said, “Okay, well, let’s get some food in you first. What do you want? An omelet? Soup? Sandwich?”

I placed my order, and after she called it out to the kitchen, she picked up a telephone by the register.

“Hi, Ginny?” she said into the phone. “It’s me. You got a room? I got a young fella, his car broke down on the highway and he’s here now. He’ll probably be here overnight. Can you pick him up? He’s got a parakeet with him, so you’ll have to suspend your no-pets rule.” Here she laughed. “I’ll call down to George, see if he can help him.”

She cradled the phone and immediately made another call.

“George, I know it’s late, but I got a young fella with a…” She placed her hand over the mouthpiece and called to me. “What’d you say was wrong with the car?” And then, back to George, “He says his transmission is slipping. Well, he’s here right now. You can come on up and he’ll tell you where the car is. And George, he has to be in San Francisco in four days.” She smiled at me and winked. “And I don’t think he’s got a lotta money to spend.” This time she didn’t smile or wink.

George arrived ten minutes later, said he might have to drive clear to Des Moines for a new transmission, but to let him think about what he could do. Shortly after that, Ginny from the motel showed up and gave Critter and me a ride to the humble roadside lodgings—which turned out to be a hundred yards away from my car.

“I appreciate the ride and all,” I said, “but you didn’t need to pick me up. It’s very kind, and I’m grateful, but it wasn’t even half a mile.”

“I figured it was getting a little chilly this evening,” she said.

“It’s not too cold for me,” I replied.

She looked at me, then at Critter, then back at me.

“I wasn’t worried about you.”

The next morning George called the motel and informed me that he had managed to find a used transmission 20 minutes away. “I can have it ready for you tomorrow before noon. It’ll cost $300, though.”

Only later did I learn that a new transmission would have been easier for him to find and would have cost me three times as much.

I had dinner at the diner again that night, and my benefactress told me about the local sports bar.

“It’s where a lot of the men like to go at night and watch the baseball and tell lies and drink their beer,” she said.

At the bar, everyone agreed that George was a good mechanic and his price was fair. Everyone argued about how long it would take me to drive to San Francisco, with estimates ranging from two days (driving 12 hours a day) to a more modest four days. A bottle of Bud landed before me and I never found out who paid for it.

Cowboy Motel, Amarillo, TX. “Ya’ll come back now.” Photo by John Margolies

I have no idea what George the mechanic’s political leanings were, nor what Ginny the motel-keeper thought about feminism. I couldn’t tell you how the old lady at the Parting of the Ways regarded the growing national debt, or what Bob from Lewiston felt about immigration policies.

Our new president, Joe Biden, was perhaps being a little Pollyanna-ish when he said, shortly after taking office, “The nation is not divided. You go out there and take a look. You talk to people. You have fringes at both ends, but it’s not nearly as divided as we make it out to be.”

America is fractionalized. In so many ways. And it always has been. But I get what Biden was driving at. Even the most mundane road trip is likely to prove that far less divides us than unites us.![]()

Mark Orwoll formerly was International Editor of Travel + Leisure. His articles have appeared in Town & Country, Condé Nast Traveler, The Travel Channel, Frommer’s Travel, and numerous other magazines and websites.