Every community has at least one charcutería selling Jamón Ibérico, sausages and fresh pork cuts. Photo by Teresa Bitler

By Teresa Bitler

By the time we break for lunch at a reservoir in the Extremadura region of Spain, I’m craving the local specialty. Ibérico ham, also known as Jamón Ibérico, has been a staple on my plate for breakfast, lunch and dinner since I arrived a few days ago.

I don’t have to wait long to get my fix. Pepe Alba, a master Ibérico ham cutter and owner of El Jamón Hecho Arte and his wife pull two folding tables out of their cars, and as she sets them with wine, olives and bread, he hoists a ham leg—hoof still attached—to one of the tables. In a matter of minutes, he has filled two plates with bright red, paper-thin slices.

As I pop a slice in my mouth, the cured meat hits with a salty punch that turns into a lingering sweetness, similar to bacon. It’s nutty, too, and I detect another flavor I can’t identify. I ask Alba what I’m tasting.

“The primary flavor is,” he says, adding that while umami permeates the entire leg, different muscles have slightly different flavors. Experts describe the meat I’m eating from the maza, or main part of the ham, as having an almond aftertaste.

After several days in Extremadura, I’m beginning to understand why Ibérico ham is such a prized delicacy—not only in Spain but the world—and it starts with the Black Iberian pig.

Pepe Alba, a master Ibérico ham cutter, demonstrates how to get the perfect slice of jamón. Photo by Teresa Bitler

A Spanish delicacy

Today’s Black Iberian pig is a descendant of native wild boars and pigs brought by the Phoenicians to the Iberian Peninsula. Hairless with long snouts and long legs, they stand out thanks to their dark skin and black trotters (hooves). Earlier that morning, I easily spotted herd after herd roaming grassy meadows on the drive to a local farm with Alba. On the other side of stone walls, the pigs foraged for acorns under holm oak and cork oak trees.

Through a translator, Alba now explains that the highest quality Ibérico ham comes from purebred Black Iberian pigs that eat acorns (bellota) exclusively during the Montanera season when the acorns fall (October to March). The nuts give the meat its rich flavor while free-ranging allows the pigs to develop a Wagyu-like marbling. These pigs—less than 12 percent of all Ibérico pigs—earn a black label, and a single ham from one can cost close to $1,000. In Spain, consumers pay on average 150 to 200 Euros per kilogram, depending on how long it is cured and its denomination. In North America, an ounce costs $15 to $20.

The label is the key to determining quality. Like black label Ibérico ham, red label hams come from free-ranging pigs that feast solely on acorns. However, these pigs are only 75 percent Ibérico and cost roughly 80 to 120 Euros per kilogram. Hams with white or green labels are more affordable. While both are at least 50 percent Ibérico, green label hams eat cereal (cebo) or grains such as corn before switching to an acorn diet.

The highest quality Jamón Ibérico comes from Black Iberian pigs that eat acorns like these exclusively during their last few months. Photo by Teresa Bitler

Farm Life

From Badajoz, Spain, where Alba is based, we drive south through a green sea of grass. Golden boulders and waist-high shrubs break up the landscape, and in the distance, an occasional farmhouse overlooks the scene from a hilltop. As Alba’s truck begins to climb, oak trees replace the openness, and stone walls contain the red cows common in the area.

Turning on the private road that leads to the farm, we slow to 20 miles per hour, and Alba points out a distant arena where the neighboring farmer raises bulls for fighting. It’s common to see the two industries side-by-side like this in the Badajoz province of Spain, near the Portugal border, he explains.

Manuel Albarran greets us wearing worn work boots, jeans and a black North Face jacket as we pull in front of his white-plastered house. The farm he tells us has been in his family for more than 100 years and can produce between 100 and 150 pigs annually, depending on the year’s acorn crop. That’s because each pig requires at least 10 kilograms (22 pounds) per day to reach the proper weight.

Once our group is ready, Albarran leads us across the yard, through a gate in a stone wall and into a grassy field dotted with mushrooms. Half of the trees here have the deep reddish-brown trunks of freshly stripped cork oak trees, and acorns litter the ground at their base.

Behind another stone wall, half a dozen Ibérico pigs amble into view, heading towards a muddy puddle created by recent rains. When they see it, several break into a trot. Albarran tells our group that the pigs here were born in May or June and ate cereal until they became adults at 18 months when he released them into the fields to eat acorns. While eating acorn is essential to the meat’s flavor, the animals’ constant movement as they forage helps develop the perfect balance of muscle and intramuscular fat for a melt-in-your-mouth feel.

The black-hoofed pigs used to make the highest quality Jamón Ibérico feed exclusively on acorns the last few months of their lives. Photo by Teresa Bitler

Farmers like Albarran monitor the acorns in their fields, and when the pigs have cleared one field, they move the animals to the next. This continues until the pigs either roughly double their weight or the acorns run out. The slaughter usually takes place a few weeks into the new year.

“The work is really, really hard, but I love nature, and I love being my own boss,” Albarran says. “I’m proud to grow these animals.”

Processing the meat

Nearby, the processing factory of Señorío Porrino is quiet now, but that will change when the pigs arrive in a few months. Alba escorts us to a small room where workers will place the carcasses on a table and divide them into parts. The hams then move to the storage room next door, which is kept at 98 percent humidity and 2 degrees Celsius (35.6 degrees Fahrenheit). Larger hams go on the floor with progressively smaller hams on top, each layer separated by sea salt. During this curing process, the salt draws moisture out of the ham and creates an inhospitable environment for bacteria to grow. It also lends the sweet meat its saltiness.

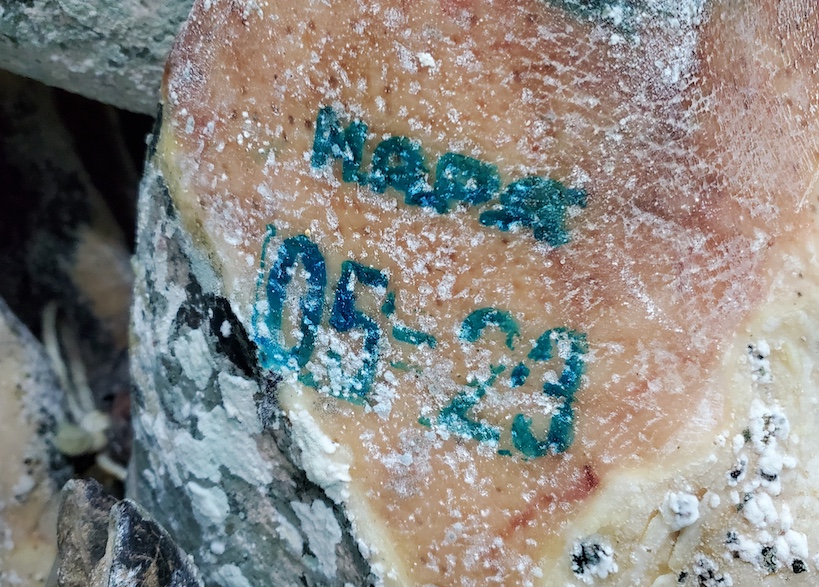

After two weeks, workers rinse the hams and hang them to dry for 90 days. Prepping the ham for aging involves two steps. First, workers stamp the week and year (for example, 05 23) on the ham to keep track of the meat and how long it has aged. Next, they rub the meat with oil to keep insects and pests from the ham.

The numbers stamped on an Ibérico ham indicate the week and year the ham was produced. Photo by Teresa Bitler

Aging can last anywhere from two to four years, but most Ibérico hams spend three years hanging. Weight is the best indicator of when the aging process is complete. When ready, a ham will weigh roughly half of what it did when it arrived.

Elina Sanchez, a guide at the Museo Jamon in Montesterio, Spain, says factories use the same process to turn the meat into Ibérico ham that families have used for generations on their farms. The only difference is factories use machines while at-home processing is a social event with friends and neighbors being invited to help.

“Some people still do it, but it’s dying out,” she says of home processing.

Serving and storing

At the reservoir, Alba gives a demonstration of how to properly slice Ibérico ham. Held at roughly a 45-degree angle in a ham stand, it sports a deep red groove where Alba has already made cuts.

Ibérico ham ages from 18 months to four years, depending on the label it will be sold under. Photo by Teresa Bitler

“You must cut softly,” he says, making a gentle sweep from front to back with the sharp carving knife. He holds the slice up to demonstrate how it should be paper-thin.

When he has cut the last piece, he covers the exposed flesh with a flap of ham fat. Properly stored in a cool, dry space, the ham can last six to eight weeks until the meat has been carved off. Then, you can ask your butcher to cut the bone into smaller pieces to flavor soups.

Going international

Jamón Ibérico is made from Black Iberian pigs, the descendants of wild boars and pigs brought to the area by Phoenicians. Photo by Teresa Bitler.

Getting an authentic ham in the United States may be easier today thanks to Amazon, but it still is complicated, Alba says. Specialty stores in the U.S. carry black label Ibérico ham, but these American outlets face stiff competition from other European countries and China for the meat. Plus, China is willing to pay $200 to $300 more per ham than American consumers and to purchase the whole pig, including innards, making them an attractive market. And don’t even think about trying to bring one back from Spain. The USDA prohibits bringing Ibérico ham into the U.S. from Spain.

However, a few farmers—Iberian Pastures, Acornseekers and Encina Farms—now raise Ibérico pigs in the U.S., although they mostly sell fresh pork, not cured meats, at this time. (Hams take time to age.) Likely, the American version will be different. For example, Iberian Pastures feeds its pigs pecans, peanuts and sunflower, giving its meat a nutty taste.

Regardless of the finishing nut, these Ibérico hams are a far cry from American country hams, which are made from larger, leaner pig breeds and are typically smoked. The American ham may even taste sweet if brown sugar is added during the curing process. Additionally, American country hams lack the health benefits of their purebred, acorn-fed Ibérico counterparts, which boast high amounts of monounsaturated fatty acids. In other words, like olive oil, Ibérico ham is a “good cholesterol” and can help prevent cardiovascular disease.

Jamón Ibérico features the savoriness of umami, the fifth taste alongside sweet, sour, salty and bitter as the primary taste. Photo by Teresa Bitler.

Alba says there’s no substitute for Ibérico ham raised in Extremadura. Sitting near the reservoir, sipping wine with fresh slices of meat, I agree.![]()

Teresa Bitler is a travel journalist based in Arizona. Previously for EWNS she followed Kentucky’s Bourbon Trail.