Most bourbons age for four years in new, charred oak barrels like these in a Louisville rickhouse. Photo courtesy of Louisville Tourism

By Teresa Bitler

A flight of five bourbons sits on the thickly varnished wooden bar inside a Louisville, KY tavern. Nearby, office workers and tourists escaping the heat of the day enjoy the tavern’s justifiably famous fried chicken and pork ribs.

The food is tempting, but I’m going with samples of middle-of-the-road Kentucky whiskey simply because these are the brands favored by most Americans. Yes, bottles of artisanal and small batch bourbon look down from the upper shelves behind the bar, but the affordable brands before me represent what’s popular today.

Produced in a massive, factory in Bardstown, Kentucky, Evan Williams is my usual choice, but I’m surprised how one-dimensional it is in a taste test comparison. There’s no spice or wood, just notes of honey. Wild Turkey 101 is made near the Kentucky River in the tiny town of Lawrenceburg, but it tastes like a Werther’s Original candy until it finishes with the sweet heat of Red Hots cinnamon.

From there, the bourbons get more complex. Willet Pot Still Reserve Bourbon, aged in rickhouses in the rolling hills near Bardstown, smells of cherry pie on a Kentucky summer afternoon but tastes of caramel, buttered popcorn, and black pepper. Meanwhile, Very Old Barton 100 Proof isn’t as sweet as the others but tastes almost like a snickerdoodle with hints of butter, vanilla and baking spices.

Knob Creek Small Batch 9 Year, a blended bourbon made within earshot of the railroad in Clermont, Kentucky, is the final selection. When combined with a few drops of water, flavors resembling brown sugar, vanilla and charred oak slowly yield to a mix of cayenne pepper and rye spice. American whiskey can be complicated, especially after five shots of bourbon.

America Baptized in Bourbon

Bourbon’s story starts with the arrival of Europeans, who replaced the barley they used to make whiskey in the Old World with the corn and rye that thrived in their new American home. As colonists moved West, so did whiskey production. Distillers especially loved Kentucky because of the purity natural limestone filtration gave the territory’s water.

Farmers used their new whiskey to preserve excess crops and barter for goods and services. But it had even more important purposes. Bourbon was a distilled beverage at a time when it was dangerous to drink bacteria-infested water from a lake or creek. It served as palliative medicine to treat everything from fever to sexually transmitted diseases.

“Americans had to drink alcohol to survive,” says Peter Newberry, co-owner of The Prohibition Bourbon Bar, which is deceptively located inside the Newberry Bros. Coffee shop in Newport, KY. “Back then you drank water, you died.”

Bourbon emerged as its own style when people started asking for whiskey sold from barrels marked “Bourbon” after its Kentucky starting point. From there, wholesalers transported it down the Ohio River to New Orleans. Although the recipes varied, “Bourbon whiskey” shipped in charred barrels had a sweetness locals preferred over other variations.

American Whiskey Evolves

Despite its good reputation, bourbon whiskey—and whiskey in general—was loosely regulated. Wholesalers added water to stretch the product and then covered up the dilution with prune juice, tobacco spit and other unsavory ingredients. Attempting to minimize this, Congress passed the Bottled in Bond Act of 1897.

To be bottled in bond, a whiskey had to be made at a single distillery by one distiller in one season, aged at least four years and bottled at 100 proof. This proof guarantees that the spirit contains 50 percent alcohol by volume and hasn’t been watered down. The bottled in bond designation still often appears on labels today.

The Kentucky Bourbon Trail features 43 distilleries throughout the state, including Jeptha Creed Distillery in Shelbyville. Photo by Teresa Bitler

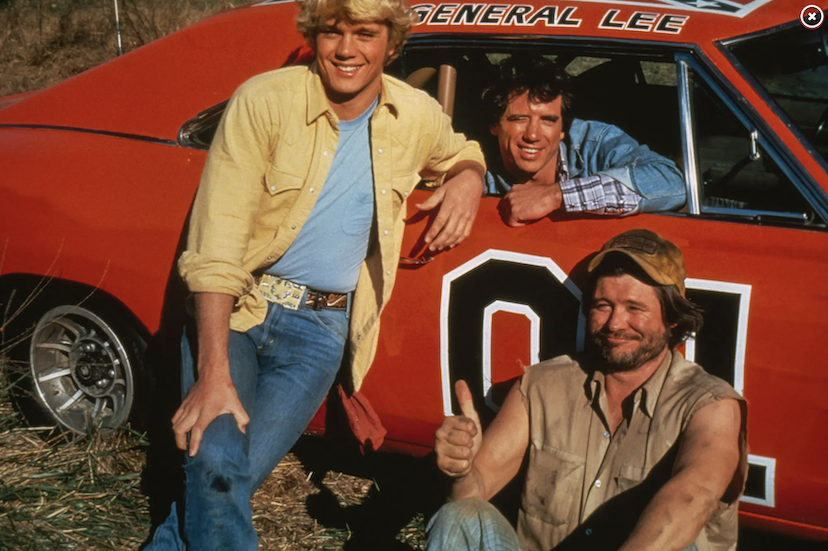

Even after the Bottled in Bond Act, bourbon didn’t have a legal definition. Two events changed that. First, Prohibition created a shortage when it took effect in January 1920. Bootleggers rose to the challenge, transporting moonshine and whiskey made overseas across stateliness. Their fast cars and fancy driving led to the birth of NASCAR and gave whiskey its outlaw reputation, which lives on in “Dukes of Hazzard” reruns.

When Prohibition ended in 1933, the industry barely had enough time to recover before it was shut down again, this time to produce industrial alcohol for use in World War II. Lewis Rosenstiel, head of Schenley Distillers Corporation, took note. Fearing another shutdown and shortage during the looming Korean War, he created a surplus of his brands, most notably I.W. Harper.

Only this time, the federal government didn’t halt production, and Rosenstiel had more whiskey than he could sell before the tax on it became due. His predicament forced him to ask Congress to extend the amount of time whiskey could age before being taxed from eight to 20 years.

From 1979 to 1985 “The Dukes of Hazzard” was one of the most popular shows on television. It featured the Duke Boys, who often transported illegal moonshine whiskey while pursued by amusingly incompetent police. “Meet the Duke clan,” the program beckoned. “They’ll do anything for a good time, a good cause or a bad woman. You’re in Hazzard County where the lawmen are crooks, the good guys are outlaws and ever’body’s inlaws.”

A Distinct American whiskey

This gave him more time to sell his surplus whiskey, but he also needed a larger market. With his eyes set on international drinkers, he sent a case of bourbon to every American embassy in the world, making it synonymous with the U.S. He also petitioned Congress to define bourbon and make it a distinctly American product. A joint resolution passed in 1964 did just that.

To qualify as a bourbon, a whiskey must adhere to six rules. It must be made in the U.S. (although not necessarily in Kentucky) use at least 51 percent corn and be aged in new, charred oak barrels. Finally, bourbon cannot have any artificial coloring or flavor.

Not all distillers label their whiskeys as bourbon. For example, Jack Daniel’s refers to itself as Tennessee whiskey (perhaps because it’s located in Lynchburg, Tennessee) to call attention to its practice of filtering its bourbon through 10 feet of hard sugar maple charcoal, according to brand historian Nelson Eddy. The process mellows Jack Daniels’ products, which otherwise meet the definition of bourbon.

Colleen Thomas, vice president of operations for the Kentucky Distillers’ Association explains: “Tennessee whiskey can legally be bourbon. However, Tennessee whiskey doesn’t want to be bourbon.”

Despite bourbon’s designation as a uniquely American product, domestic drinkers in the late 1960s and 1970s began shunning their father’s drink of choice in favor of vodka and other spirits. Yet, while bourbon struggled in the U.S., it gained a toehold internationally. Rosenstiel’s I.W. Harper entered 110 markets in the 1960s. Jim Beam followed suit, opening bottling plants in Germany and entrenching itself on U.S. military bases around the world.

Bourbon’s fortunes changed in 1984 with the introduction of the first single barrel bourbon, the first bourbon labeled small batch in 1992, and the very limited Pappy Van Winkle 20 Year in 1994. Increased marketing publicized the new products. The Kentucky Bourbon Festival debuted in 1991 and the Kentucky Bourbon Trail welcomed its first guests in 1999.

Kentucky’s Bourbon Trail

Over the years, the Kentucky Bourbon Trail has expanded to include 43 distilleries, stretching from where Cincinnati, Ohio’s suburbs spill into Kentucky to the state’s southern border with Tennessee. Most distilleries are found around three cities: Louisville, Lexington, and Bardstown. Combined, these distilleries attracted more than 2.5 million visitors in the last five years.

A boat tour on the Kentucky River is an excellent place to begin developing an appreciation for America’s whiskey. From there drive along the trail to see the outcroppings of limestone that filter iron and other minerals out of the area’s water, making it ideal for producing bourbon. Mammoth rickhouses packed with barrels of aging bourbon are everywhere, and most are covered with a black fungus produced by ethanol gas given off during the distillation process.

George Harrison portrays Tom Bullock, the first Black American to write a cocktail recipe book, at Evan Williams’ The Ideal Bartender Experience. Photo courtesy of Louisville Tourism

If you stop by the Evan Williams distillery in Louisville you’ll meet Tom Bullock, or at least an actor portraying him. Bullock was a celebrated pre-Prohibition bartender, the first Black American to publish a cocktail book who today thrives as a raconteur of all things bourbon.

The Kentucky Bourbon Trail isn’t the only dedicated whiskey trail in the area. Louisville has the Urban Bourbon Trail, featuring local restaurants and bars like the Bourbons Bistro with its menu of roughly 200 bourbons. In Tennessee, the Tennessee Whiskey Trail showcases 25 distilleries, including Jack Daniel. This trail fans out through the state, with distilleries often tucked along tree lines and or on the outskirts of small towns.

Bourbon today

Today, Bourbon and whiskey tourism is booming thanks to the colorful bars and restaurants along the trails. Bourbon blogs and YouTube channels also introduce drinkers to new brands. The social media buzz is credited with energizing the craft cocktail movement.

Understanding what gives bourbon its flavor helps in tasting and enjoying it. Although the mash—the mix of grains used to make the bourbon—influences taste, Newberry says it’s the new, charred oak barrels that give the spirit most of its flavor and set it apart from scotches and whiskeys made elsewhere.

He explains that toasting the barrel caramelizes the sugars inside the wood. As temperatures change, the alcohol moves in and out of the wood, giving it the sweet, vanilla notes of a Kentucky Butter Cake. The climate also causes the alcohol to evaporate, resulting in bourbon needing to spend less time maturing.

Even if you don’t take a tour, most distilleries on the Kentucky Bourbon Trail offer flights, and short pours of three or more bourbons for comparison. Photo by Teresa Bitler

By comparison, Newberry says scotch and Irish whiskey age in a damper, milder climate that adds moisture. As a result, they mature more slowly, and because there’s no requirement to use a new barrel, scotch and Irish whiskey tend to be lighter in color. Both feature barley instead of corn, and the process of drying barley over burning peat gives scotch its smokey flavor.

Canadian whisky shares many of the characteristics of bourbon, but because the country has fewer regulations, it can have more diverse flavor profiles. For example, Canadian whisky can age in any type of barrel, new or used, charred or uncharred, for up to three years. It can contain 10 percent rye or 50 percent; there are no limits. As a result, depending on the Canadian whisky, it can taste as sweet as pancake syrup or as hot as black peppercorns.

“Bourbon is much more approachable than some of the other whiskeys and scotches,” says Jason Brauner, cofounder of Bourbons Bistro in Louisville and Buzzard’s Roost Sipping Whiskeys. Brauner, who introduced flights to the bourbon world after sampling wine flights in Napa, describes bourbon as being just as complex as scotch and finds most scotch drinkers have little trouble making the leap to bourbon.

Newberry, whose bar stocks roughly 6,000 bourbons as well as 250 scotches and 200 Japanese whiskeys, agrees. “I’ve had lots of people who drink bourbon and try scotch say, ‘I can’t drink this,’ but I’ve never had a person who drinks scotch say, ‘I don’t like bourbon.’”

In Louisville, the Urban Bourbon Trail highlights bourbon bars and restaurants like those on Whiskey Row. Photo courtesy of Louisville Tourism

How to Taste and Enjoy Bourbon

Bourbon shouldn’t be intimidating, according to mast taster Jackie Zykan, whose highly trained palette helps her identify flavors and create bourbon blends. She advises curious drinkers to tell the bartender what you like and ask for suggestions. Or order a flight of three to five short pours of different whiskeys that are served together in a specific order for comparison.

“The pressure and intimidation surrounding bourbon is so silly,” she says. “The whole point is simply to enjoy it.”

When tasting bourbon, Zykan, instructs people to forget what they know about wine tasting. Don’t swirl or stick your nose in the glass. Just breathe the aroma then, take a quick sip. Follow that with another quick sip.

“You’re going to get the sweetness of the corn and vanilla and generally some baking spices,” she says. “I like to think of bourbon as Christmas in a glass.”

Zykan adds that you don’t have to drink bourbon neat or even diluted with a few drops of water. It’s perfectly fine to enjoy it in a cocktail, like an Old Fashioned that combines bourbon and Angostura bitters and is garnished with an orange peel and cherry.

Ultimately, bourbon is meant to bring people together, not divide them based on how fine-tuned their palette is. It’s about coming together and sharing stories, according to Newberry.![]()

Teresa Bitler, the author of four guidebooks, loves exploring culture and history while on the road. Her work has appeared in National Geographic Traveler, Wine Enthusiast and Saturday Evening Post. This is her first story for the East-West News Service.