Cheesecake and an Egg Cream. Ah, pure bliss. Cheesecakes from Juniors and S&S Cheesecake are shipped around the world. Photo by Mark Orwoll

By Mark Orwoll

The intersection of culture and desserts reveals much about America.

Scene: an overcast Tuesday morning at the corner of Flatbush and DeKalb, downtown Brooklyn. As a location, it doesn’t get any more New York than this. I have driven more than two hours and 80 miles round-trip to sit here, in this cultural-culinary landmark in the heart of the borough, for a simple reason.

To eat cheesecake.

But not just any cheesecake: a slice of Junior’s No. 1 cheesecake, New York-style, washed down with a tall glass of Fox’s U-Bet egg cream.

Yeah, you got your New York pizza. And yeah, sure, you got your New York bagels. But there is no more New York food than the unadorned, creamy slice of sweet heaven on earth that’s beckoning to me at this very moment. Especially when paired with an egg cream.

I am sitting on the sunny, wide-windowed terrace of Junior’s Cheesecake restaurant, with its pressed-tin ceilings, tiled floors, and eye-level views of the Brooklyn street life: bike messengers impervious to traffic, pairs of young Orthodox Jewish moms pushing strollers, a South Asian man in a kaftan and a painted forehead. In this inimitable milieu, my slice of New York cheesecake is the culinary equivalent of Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.”

The (eggless) egg cream consists of a 16-ounce glass holding a couple ounces of Fox’s U-Bet chocolate syrup, four ounces (or so) of milk, and topped off with plain seltzer. The cheesecake is authentic, the real deal—no fancy-pants fruit topping, no Graham-cracker crust, just loaded with eggs, cream cheese, heavy cream, sugar, and assorted other health foods. The pairing isn’t a cheap snack. At $8.75 for a slice of cheesecake and $4.50 for the egg cream, my wallet is considerably lighter (just as I am considerably heavier) than when I entered. One gets the feeling that customers are paying a premium for the nostalgia value. But each visit here is worth more than a handful of wadded dollar bills.

As I finish my dessert, two twenty-something Japanese women take seats at a nearby table and begin talking in their native tongue. Take one guess what they order when the waitress stops by.

When my own server, Karina, comes to my table with the check, I ask her opinion.

“You’re an expert,” I say. “Which style of cheesecake is your favorite?”

She doesn’t even hesitate.

“I like the strawberry,” she answers. “That, or the red velvet.”

I stare at her, open-mouthed, horrified. “Fraud!” I say, melodramatically (but sweetly, sweetly). It’s as if a man named O’Malley went into a pub called Keegan’s on St. Paddy’s Day and ordered a Stella Artois. “But what about your customers? What do they prefer?” I’m afraid I sound desperate.

Her answer (which may have been more to quiet down the madman in front of her than based on actual fact): “Oh, definitely the original! Definitely.”

Desserts Require A Secret Ingredient To Make It ‘Ours’

Junior’s, which has sat on this corner since election day, 1950, didn’t invent the cheesecake, of course. Nor is there universal agreement that it’s the best in New York. Less-publicized but equally revered, is S&S Cheesecake, a 60-year-old institution in the Kingsbridge neighborhood of the Bronx. Yair Ben-Zaken, the owner, is fully aware that there is more to cheesecake than its ingredients.

More treat than dessert, pralines are popular throughout the South and along the TexMex border. A candy made of brown sugar, pecans,cream, corn syrup, butter, and vanilla extract is sold at Mexican restaurants.

“Our founder, Fred Schuster, god bless, he’s still alive, Fred would say, ‘Baked with love, served with pride,’” says Ben-Zaken. “We have people coming here after church, after synagogue, for birthdays, whole families, you name it.”

The recipe is secret, but talk to Ben-Zaken a few minutes and he’ll begin to spill. “The formula is very special, the way we bake it,” he says. “The idea is to make small batches and make it consistent. People come in and see me baking myself. I use a 550-degree oven! What!? What!?” Ben-Zaken cups his hand over the phone as someone nearby shouts at him. “Wait. My people are yelling at me that I’m giving away our secrets.”

But despite the passion that goes into S&S cheesecake, the actual ingredients are hugely important, says Ben-Zaken. “I always use the same providers, but I still always check the quality. I always test the cream cheese. First thing I do, I wash my hands, then I stick a finger in one corner. Don’t tell nobody, but that’s how I know.”

Despite being less famous than larger bakeries, like Junior’s, S&S Cheesecake has found its way onto the menus of such national restaurant chains as Bobby Van’s and Mortons The Steakhouse. “But they don’t say it’s S&S Cheesecake,” says Ben-Zaken, “because they want everyone to think they made it! But people can tell. They ask if it’s ours. It’s because of the way we bake it. It’s our signature.”

Maybe that’s the key to regional desserts, whether it’s cheesecake in New York, aqutaq in Alaska, or shoofly pie in Pennsylvania: they make you think of home.

The Intersection of Culture and Dessert

This is the point in the story where a writer feels almost obligated to quote Proust. Instead, I’m going to quote the late (and thoroughly American) cookbook author Jeff Smith from The Frugal Gourmet Keeps the Feast (William Morrow & Co.): “Feasting is closely related to memory. We eat certain things in a particular way in order to remember who we are. Why else would you eat grits in Madison, New Jersey?”

Blue Bell Creameries in Brenham, TX makes 52 ice cream flavors.

The more I looked into the intersection of dessert and culture, the more I realized that the food itself—that is, the ingredients, the preparation, even the taste—sometimes has less to do with a sense of place than the manner in which the food is consumed. For example, any New Yorker worth his 212 or 718 area code will tell you there is only one way to eat a pizza slice: folded in half lengthwise, held in the air nose high with two hands, then gently lowered into the mouth. You think this is silly? Mayor Bill de Blasio didn’t think so when he was ripped apart in the New York media for eating a slice of pizza with (shudder) a knife and fork! He was a laughingstock for weeks. I wouldn’t have been surprised to read about a recall vote. There are some foods, desserts and otherwise, that are intended to be eaten a certain way or not at all.

I have an example. When my editor assigned me to write this story, he seemed to have been under the influence of a dessert coma, rhapsodizing about Blue Bell ice cream from Texas, Indian “candy” (actually cured salmon with maple syrup) from British Columbia, and, especially sopaipillas.

“New Mexico, for example, has the sopaipilla,” he wrote in his assignment email, “a piece of fried pastry that is dusted with cinnamon and confectioner’s sugar, then topped with honey.” And then came his own Proustian-madeleine moment. “I usually gnaw off one of the corners and squirt the honey inside.”

Sopaipillas are popular throughout the American southwest, especially in Hispanic areas. Photo by Miia Hebert

His New Mexico comment made me think of my 87-year-old step-mother, a native Minnesotan who now lives in the Land of Enchantment. So I called her and asked about her favorite treats growing up in the North Star State. She didn’t even hesitate.

“My favorite candy bar is the Nut Goodie,” she said, “made by the Pearson Candy Company of St. Paul. They don’t even make them all year round! It used to be my mother’s favorite candy bar, and it’s still mine. They were much bigger when I was young. Anybody from the Midwest knows a Nut Goodie.”

Now, Nut Goodies are tasty, no doubt, but that doesn’t stop companies elsewhere in the country from marketing their own versions—like the nearly identical Goo Goo Clusters made by the Standard Candy Company in Nashville, Tennessee. Yes, they’re both chocolatey and nutty, but I wouldn’t want to stand between a Minnesotan and a Tennessean arguing over which of their tasty treats was best.

My step-mom’s memories were a perfect distillation of the ties between culture, identity, and desserts: a high degree of specificity (“…made by the Pearson Candy Company”); limited availability (“They don’t even make them all year round”); family ties (“It used to be my mother’s favorite”); a longing for the good old days (“They were much bigger when I was young”); and the regional association (“Anybody from the Midwest knows a Nut Goodie”). Which proves what I have said many times: if you want to know something about culture, or life in general, talk to an octogenarian.

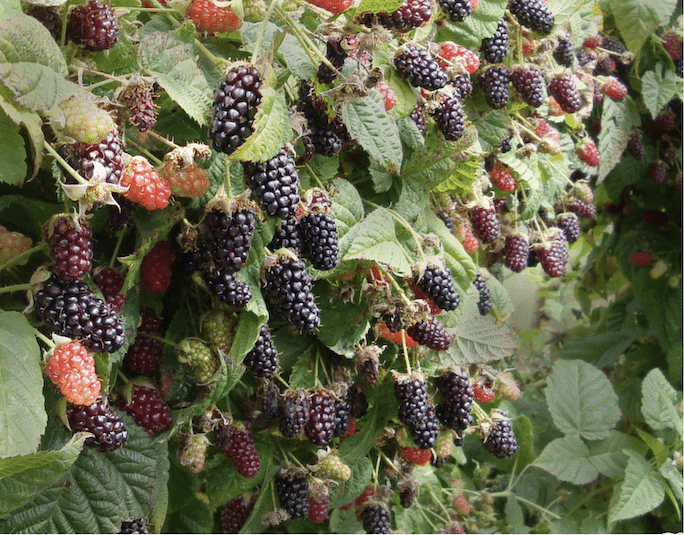

Marionberry Mania

Perhaps nowhere is a treat more identifiable with a specific place than Oregon, where science created the one and only marionberry in 1956 (the exact date is debatable, but sometime in the decade after World War II is generally agreed on).

Marionberries look like blackberries, but instead of growing on a bush they grow on a vine. Their glossy dark shine turns a deep purple when picked.

“The reason the marionberry is beloved here is, first, that it was developed here, and that it thrives and grows only in the Salem area and along the Willamette Valley,” says Darcy Kochis, the marketing director of the Oregon Raspberry and Blackberry Commission, a trade group. “You’re never going to get it fresh outside Oregon.”

Most Americans have never even heard of the marionberry—unless they watch the cult TV show Portlandia. The second season of that offbeat series featured an episode titled “Brunch Village,” in which a new brunch-focused restaurant becomes a trending topic because of its marionberry pancakes. The front page of the newspaper features the eatery’s marionberry pancakes. Lines stretch around the block to order the marionberry pancakes. Would-be diners confront street thugs and surly hostesses to consume marionberry pancakes. All of which left TV viewers wondering: “Wait! Is there really such a thing as marionberries?”

Marionberry pie

“Marionberry pie is our state pie,” says Kochis. “You can get marionberries in jams or muffins or pies. Go to any classic diner in Oregon and marionberry pie is on the menu. There’s nothing that beats the flavor of marionberry, the rich tart-sweet taste, the reddish-purple coloring, the berry we all grew up with and made into pies with our mothers and grandmothers.

“Growing up in Oregon, berries are part of our culture,” she continued. “I’m in my early forties, and I grew up picking berries in the forest for fun. A lot of us my age picked berries as a summer job. There are a lot of people here who grew up like that. It’s rooted in us.”

Official Desserts

You wouldn’t think that tasty desserts, made from recipes passed down through the generations, like marionberry pie, would have to be formalized in any way. Yet dozens of states have sought to legislate and celebrate their tax-payers’ tastebuds. In some cases, such proclamations were passed to placate a certain agricultural industry, say, dairy farmers or corn growers. In other cases—well, it’s just possible the solons were high on sugar. Take, for example, the Vermont legislation that named the official state pie:

“When serving apple pie in Vermont, a ‘good faith’ effort shall be made to meet one or more of the following conditions: (a) with a glass of cold milk, (b) with a slice of cheddar cheese weighing a minimum of ½ ounce, (c) with a large scoop of vanilla ice cream.”

Forget education, homelessness, under-employment, and the over-population of Subaru Foresters! What needs to be done in Vermont now, and I mean right away, is to decide how much cheddar cheese should be served with a slice of apple pie!

Apple pie is the All-American dessert. Popular throughout the entire US, it can be served with American cheese or ice cream but most people prefer it unadorned. Photo by JeffreyW.

I don’t mean to isolate Vermont, which, after all, grows tons of apples and whose cows produce abundant milk, cheese and ice cream. Let’s celebrate our resources, traditions, history, and the like. That sort of pride is why we have such official state desserts as the whisky-soaked Lane cake (Alabama), peach pie (Delaware), Key lime pie (Florida), pumpkin pie (Illinois), sugar cream pie (Indiana), blueberry pie (Maine), Smith Island cake (Maryland), Boston cream pie (Massachusetts), the ice cream cone (Missouri), and kuchen (South Dakota). That’s not to mention official state snacks (popcorn in Illinois, yogurt in New York, boiled peanuts in South Carolina, tortilla chips and salsa in Texas, Jell-O in Utah), official state treats (whoopie pie in Maine), official state doughnuts (Boston cream doughnut in Massachusetts), official state cookies (biscochito in New Mexico), official state beverages (coffee milk in Rhode Island), and official state pastries (kringle in Wisconsin).

Sense of Place

All of those culinary proclamations, accolades, and honorifics speak to one thing: these foods are part of our respective regional identities, as much as our slang, our manner of dress, and our world view. I’ve been fortunate to taste regional foods around the country and the world, and I never fail to be impressed by the eager, expectant look on a local’s face when he or she serves you a dish that only they know about.

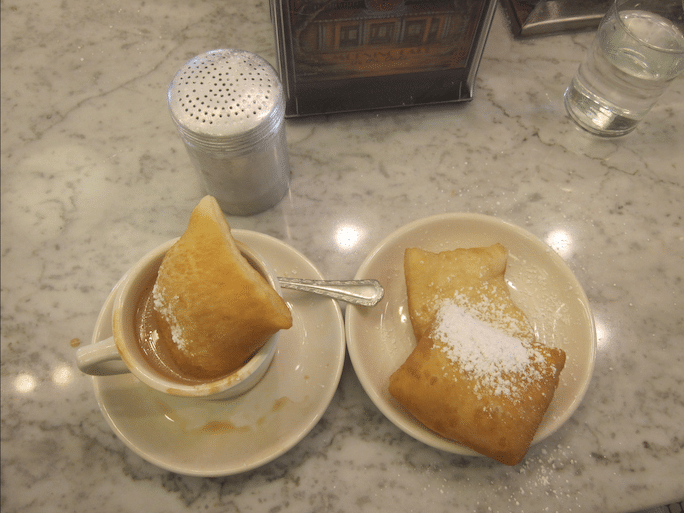

Long associated with New Orleans coffee shops Morning Call and Café Du Monde, the beignet is a donut that can be covered with powdered sugar and eaten or dipped in a hot cup of New Orleans coffee with chicory. Photo by Infrogmation of New Orleans

To me, a beignet is just a doughnut with a Cajun accent. But I would be taking my life in my hands if I were to say that in New Orleans. I remember sitting one day at a café called Morning Call, a NOLA institution that relocated to City Park after Hurricane Katrina. I ordered a coffee and a plate of three beignets. When the pastries arrived, I began to pour powdered sugar over them oh so delicately. My Cajun friend who was escorting me snorted and yanked the sugar container from my hand.

“You got to really knock it hard,” he said, spreading white powder all over my coffee, the napkin holder, my knife and fork, my lap, everywhere. “You don’t have enough until you can write your name on the table.”

The waiter who served us eyed me contemptuously, arms folded, and nodded his head slowly in agreement. I had just been schooled, New Orleans-style.

I generally prefer desserts without such harsh rules, though. Salt-water taffy (a treat more than a dessert, I admit) would not taste the same if it weren’t made on the Jersey Shore, preferably, but not necessarily, behind a display window on a boardwalk with the sounds of roller coasters and shooting galleries in the background. I’ve eaten the delicious, pie-like kuchen in both North Dakota and South Dakota; it’s the first thing I would order back in the Dakotas–and the last thing I would order anywhere else. At a dinner at the Governor’s Mansion in Frankfort, Kentucky, I wallowed in the chocolate-walnut goodness of Derby-Pie. I can’t imagine eating it (or even finding it) anywhere but Kentucky. (Although that night I developed a fondness for mint juleps that, somehow, defies state borders.)

Derby-Pie exemplifies the fierce regional pride people take in their desserts. In fact, in defending its recipe, the Kentucky Kern family, which developed the recipe in 1954, has sued to protect its trademarked name dozens of times. Derby-Pie has become the “most litigious confection in America,” according to the Electronic Frontier Foundation. Now that’s what you call a regional dessert.

Amish in Pennsylvania started making Shoofly Pie in the 1880s. It’s a molasses crumb cake that got its name from a brand of molasses popular in the late 19th century. Sixty years later it became a song: “Shoo Fly Pie and Apple Pan Dowdy, Makes your eyes light up, Your tummy say, ‘Howdy.’ Shoo Fly Pie and Apple Pan Dowdy, I can’t get enough of that wonderful stuff.” Photo by Syounjan Taji, Wikimedia

Some desserts belong to a specific place. Even if they travel well physically, they lose something ineffable in the transition across state lines. Coca-Cola cake would be disgusting outside the South, but drop me off in the Carolinas and yes, I’ll have two slices, please. The Amish-inspired shoofly pie (whose molasses, brown sugar, cinnamon, nutmeg, and salt give it a distinct coffee-cake taste and consistency) might taste good in Idaho, but it could never taste as delicious as in a roadside diner in the Pennsylvania Dutch town of Bird-in-Hand. Ex-GI’s, newly returned from World War II, were greeted in 1946 by a swinging number (“Shoo-fly Pie and Apple Pan Dowdy”) from Dinah Shore that sang the praises of that fabled dessert.

I have come to realize that desserts define us. They are where we are. In some respects, they are what we are. And it would be a shame ever to lose that.![]()

Mark Orwoll formerly was International Editor of Travel + Leisure. His articles have appeared in Town & Country, Condé Nast Traveler, The Travel Channel and Frommer’s Travel. His previous stories for EWNS discuss Driving America’s Highways and Rediscovering America through our shared history.