Bears with tourists: At Alaska’s National Parks, visitors interact with brown bears without any barriers between them. In the past 20 years, as coverage of bears in the wild on TV shows and social media has increased, “bear tourism” to Alaska has increased. Photo by RC Staab

By R.C. Staab

Having ventured to the edge of the Arctic to swim alongside wild orcas in Norway, tracked lions across the sunbaked savannas of the Serengeti and been startled by kangaroos bounding past in the Australian bush, I’ll admit I wasn’t overly hyped about seeing brown bears in Alaska. That is, until one afternoon at the Alaska Bear Camp in Lake Clark National Park, when I found myself just 20 feet from a massive brown bear— his eyes locked onto my camera, his hulking body framed by a few spindly trees. In that moment, intimidation came easy.

Brown bears can weigh up to 1,200 pounds and still outrun a human, covering ground like a freight train with fur. Yet, what struck me most wasn’t his size or speed — it was his indifference. I was surprised to find this bear only slightly annoyed by my presence, despite the centuries that humans have hunted, caged, gawked at, and exploited bears — as evidenced from Neolithic cave paintings to Roman arenas, from 16th-century German paintings to the ridiculous recent movie, Cocaine Bear.

Koalas Don’t Count

For wildlife enthusiasts and travelers keen to explore the globe, there are incredible, well-organized bear-viewing destinations on every continent except Australia — sorry, koalas are marsupials, not bears–– and Africa, where Atlas bears were hunted to extinction by the late 18th century. Whether it’s watching sloth bears snuffle through termite mounds in India or spotting the rare spectacled bear in the Andes, the world offers no shortage of unforgettable bear encounters.

With eight large national parks, Alaska may be the gold standard for seeing bears in the wild—with its salmon-choked rivers, sprawling wilderness with plenty of sedge for munching and a population of more than 130,000 brown and black bears. Tourism, in fact, is the second-largest private sector employer in Alaska, with bear watching as a significant draw.

Alaska bears are as fond of salmon as people are. This coastal brown bear has just snagged a large sockeye near Redoubt Bay Lodge, a wilderness resort reached by floatplane from Anchorage’s Lake Hood seaplane base, the busiest in the world. Salmon are the reason coastal browns reach such great size, with males surpassing 10 feet and approaching 1,000 pounds. Photo by Juno Kim, Anchorage Convention & Visitors Bureau

Where There’s Salmon, There’s Bears

In late summer as the salmon return to their spawning grounds, tourists stand in long queues to see brown bears – the coastal cousin of the inland grizzly bears – snatch salmon jumping up Brooks Falls at Katmai National Park. Outside Katmai, places such as Denali and Lake Clark offer quieter, more relaxed views, either with daytrips on seaplanes from Anchorage or in bear camps such as Natural Habitat’s private Alaska Bear Camp, surrounded by Lake Clark National Park.

At the Alaska Bear Camp, the first thing we learned was to get up with the sun, which rises before 5 am each morning in June. Because the bear camp was originally private land and only later surrounded by a national park, the bears are accustomed to strolling by at all hours. We “slept in” only to discover that we missed our first sighting. Two bears had wandered within a few yards of the lightly electrified, 3-foot fence that seemed more suited to reminding us not to leave the camp than keeping the bears out.

After digging up clams, a female brown bear with two first-year bear cubs emerges from Chinita Bay at Lake Clark National Park. Photo by RC Staab

For three days, we were immersed in bears and their world, spending mornings, afternoons and evenings on walks or jeep jaunts to unfenced viewing spots. We watched mamas play with their bear cubs, lumbering males have sex with or be spurned by females or held our breath as mildly curious bears walked within 20 yards of our group. Back at the camp we were disconnected from the world (what, no Wi-Fi in the wilderness?) so we spent our few non-bear-viewing hours learning about bears and taking a daily guided (aka guarded) group stroll on the beach. We seemingly ate like bears with sumptuous meals that featured salmon and more salmon, halibut, locally sourced vegetables and desserts made with salmon berries, rhubarb and cookies made with freshly picked spruce tree tips.

Bear viewing is serious business. Upon arrival, campers are required to empty their bags of every personal item with a scent. Snacks, deodorant and shampoo are locked in secure boxes and kept in a single tent. As Alaska bear guide Jordan Jones explains, “They can smell things from miles away.” Although there’s more than enough clams and grasses around the camp, maybe the bears would be overwhelmed by the smell of my mint toothpaste!

The Original Party Animal

Long before wildlife tours and conservation centers, bears already were embedded in our collective imagination. They’ve been showing up in myths, art and everyday life for thousands of years. Take ancient Egypt, for example. There’s evidence from carvings of bears, likely Syrian brown bears, brought in from the north. In ancient Rome, bears were often dragged into the Colosseum to fight for entertainment or kept on display for the crowds. In medieval and Renaissance Europe, they turned up in royal courts and served as the symbol of the city of Madrid, which kept seven in pits for entertainment—like the famous bear pit in Bern, Switzerland, which dates to the 1500s.

With humans interacting with bears for centuries, bears have become part of the iconography of many places. Since the 13th century in Madrid, a bear climbing a strawberry tree is the main symbol of the city’s Coat of Arms and even part of the badge of the local soccer club, Atletico Madrid. This statue is located in Puerta del Sol, Madrid’s most famous square. Photo by RC Staab

Centuries later, Leonardo da Vinci would have seen a bear near his home in Italy in order to draw the lifelike study in his notebooks which is often on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Bears weren’t just animals—they were power symbols and status statements.

Bears Are Rarely on the Menu

Maybe one reason humans and bears have managed to (mostly) coexist over the centuries is because, unlike elephants with their ivory or whales with their oil-rich blubber, bears just don’t have anything we’ve historically craved to devour or harvest to fuel our homes. Sure, some cultures have hunted them for meat, hides, or even bile in modern times—but there’s never been a global obsession with bear parts. In North America, where bear meat could be more readily harvested, it’s not allowed, and no country seems to consider bear meat a delicacy. Plus, bears vanish for months at a time in mountains or harsh climates where humans are less likely to live. When a bear hibernates deep in a den through the winter, it’s not exactly an easy target. Out of sight, out of mind. It’s almost as if their biology gave them a seasonal invisibility cloak that’s helped them dodge the worst of human greed.

That’s all changed this century. Guides at the Alaska Bear Camp say they have noticed a dramatic increase in business due to the Discovery Channel, particularly the show Deadliest Catch, and by social media where bear encounters and positive bear interaction have made people aware of the possibility and affordability of taking wildlife excursions to views bears close in the wild.

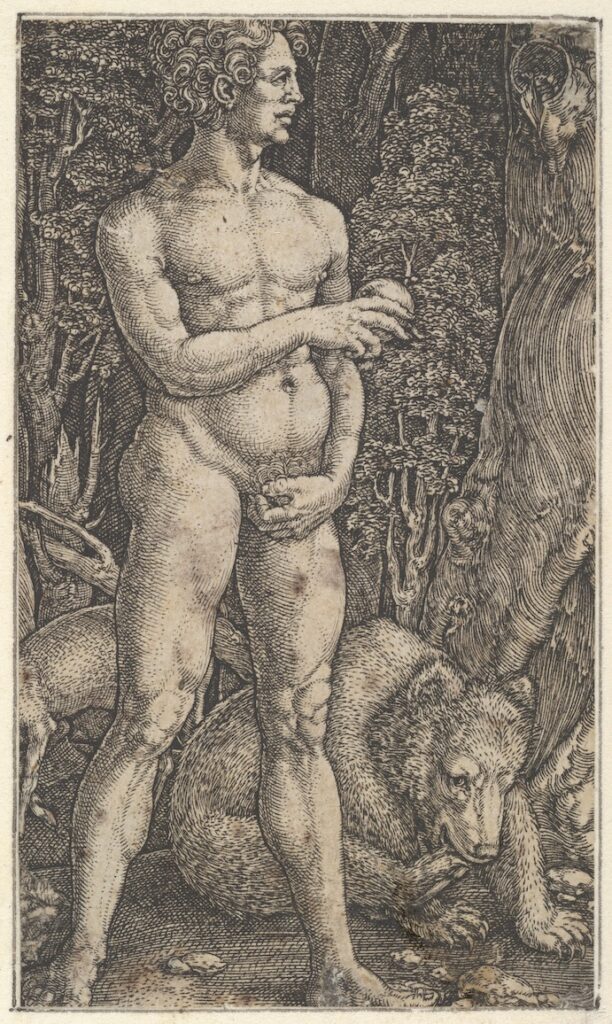

1529 German drawing of Adam in the Garden of Eden with a bear on display at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As our America’s most populous states has grown and become the center of media hype, bear encounters are tweeted, posted and blasted throughout the world. With their citizenry being both uber liberal and wildly conservative, bears are a topic of controversy. At Pine Mountain Club in the mountains north of Los Angeles, the patrol chief proclaims that bears are a major problem causing thousands of dollars of property damage with home and car break-ins. While some residents arm themselves with pots and pans to scare away the bears, other residents and vacationers happily feed the bears or inadvertently tempt them with bird feeders, scraps of food on the outdoor grill or bags of snacks in cars whose doors they can peel off in a minute.

Excluding trips to see the polar bear and panda which are subjects all to themselves, there are opportunities around the world to closely view the six other bear species: Brown Bear (including grizzlies) in Asia, Europe and North America, Asiatic Black Bear, Sloth Bear, Sun Bear, Andean Bear and American Black Bear. Because bears hibernate and then come out of the den famished, they are more predictably seen in the wild, stocking up with large quantities of food often nears rivers, bays and grassy meadows.

American black bear at the Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center. Photo by RC Staab

Beyond Alaska, here are your best opportunities for seeing bears in the wild:

Meet the Bears

The Sloth Bear: The Shaggy Sniffer Move over, tigers, for India has another star: the sloth bear. These guys are impossible to mistake with their long, shaggy coats and those ridiculously long, curved claws. They’ve got a unique way of slurping up insects, thanks to their flexible lips and missing front teeth. Unlike other bears who might bolt, a sloth bear is more likely to stand its ground if it feels threatened. Spotting them is best in Daroji Bear Sanctuary or in India’s national parks such as Satpura or Tadoba, where it often means watching them dig into termite mounds. National parks in Sri Lanka and Nepal offer opportunities in see sloth bears. Be forewarned: slot bears are mostly nocturnal so best seen at dusk or dawn.

The Asiatic Black Bear: The Moon Bear’s Mystery Often called “moon bears” due to the cream-colored crescent on their chests, the Asiatic black bear can be seen across in Japan, Russia, Turkey and the Caucasus Mountain areas of Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan. They’re similar in size to their American cousins but have longer, shaggier fur. They’re incredible climbers, spending a lot of time in trees, munching on plants. The best chance to see them in the wild is in Japan in the mountainous forests of Honshu, particularly around Mount Asama and Karuizawa. Guided summer hikes offer the greatest likelihood of sightings.

The Sun Bear: The Little Honey Lover Meet the smallest bear on the planet, smaller than humans. The sleek, black sun bears have a beautiful, crescent-shaped patch on their chest, like a tiny sunrise. They’ve got super long tongues, perfect for licking up honey and grubs. These tree-dwelling bears live in the rainforests of Southeast Asia, in places like Borneo, but their elusive and solitary nature—as well as habitat loss—makes it a challenge to spot in the wild. Bornean Sun Bear Conservation Center and Free the Bears sanctuaries in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam are the best places to see rescued sun bears and Asiatic black bears up close and learn about their care.

The Spectacled Bear: The only bear species native to South America, the spectacled bears are named for the unique light markings around their eyes, resembling spectacles. They have the most varied diet of all bears, eating dozens of plant species, including bromeliads and cactus. Spectacled bears spend even more time in trees than American black bears. The best place in the world to see is the Maquipucuna Cloud Forest Reserve in Ecuador, near Quito the capital. The forest is a favorite of these in September to December when they can feast on aguacatillo fruit. During these months, bears descend from the highlands to feast on the fruit, and sightings are not only possible—they’re often daily.

For travelers wanting a more rounded experience, Chakana Reserve—also near Quito—offers seasonal bear-viewing tours along with the chance to see Andean condors soaring overhead. In Colombia, Chingaza National Park east of Bogotá is another stronghold for these shy bears, with organized wildlife treks through the páramo ecosystem. In Peru, sightings are even possible along the famous Inca Trail or in the Chaparri Reserve in the north.

The Brown Bear on the European Continent: For travelers longing to witness Europe’s largest wild predator, the Eurasian brown bear can still be seen roaming the continent’s remote forests and mountains. Yet, observing these iconic animals in the wild is most rewarding (and accessible) through the region’s well-established bear-watching tours.

A female brown bear and two second-year bears dig for clams near Natural Habitat’s Alaska Bear Camp.

Europe’s top destination for close, frequent brown bear sightings is the wild borderlands of eastern Finland, famous for organized overnight bear-watching experiences. Here, comfortable hikes and seasoned naturalist guides allow guests to safely watch multiple brown bears—sometimes a dozen or more—gathering at twilight and through the night. Romania’s Carpathian Mountains offer another spectacular setting, home to the largest brown bear population in the European Union. Travelers can join guided dusk excursions into the ancient Transylvanian forests, venturing with experienced forest rangers to hidden observation cabins. In southern Slovenia, over 700 brown bears thrive in some of the continent’s best-preserved forests. You’ll also find remarkable, though less-publicized, brown bear tours in Bulgaria’s Rhodope Mountains and northern Greece, where local guides blend wildlife observation with hikes through rugged terrain and cultural encounters in small traditional villages

The relationship between bears and humans is continually evolving. As human populations expand and activity increases in former bear habitats, the potential for interactions rises, leading to both positive outcomes such as bear viewing and negative ones such as conflicts. Bears can become habituated to human presence, especially if food sources are involved.

Throughout North America, black bears are often found near people’s homes. Jordan says, “If you’re someone who doesn’t prefer to spend time around bears or doesn’t want to have a bad interaction, be smart with your food. That means investing a little bit of money and having bear proof containers, keeping your trash and all that sort of stuff in your garage.”

California Bears like Cookies

In Monrovia, California, the townspeople honor Samson the Hot Tub Bear, a 500-pound California black bear that came down from the foothills to eat from their fruit trees and trash cans, then jumped into residents’ hot tubs to relax. Eventually, Samson was captured and lived the rest of his life in a zoo. His fame became so widespread, that the town erected a statue in his honor and celebrates with bear statues all over town. Following in the footsteps of Samson, other bears must have recognized the likeness of their kin, because they still wander into town, break into homes to walk away with food and an occasional package of Oreos.

Alaska’s most popular tourist attraction, the Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center near Anchorage, is where people get up close to see grizzly bears and black bears.

Seeing bears up close is breath taking but know what to do if they get a little too close. It’s not about panicking; it’s about being smart. Visitors at the Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center near Anchorage – the most popular tourist attraction in the state – are giving lessons in what to do if you’re hiking or camping and unexpectedly cross paths with a brown or black bear.

Lily Grbavach, the Center’s Director of Education, says the main message for hikers and other wilderness voyagers is to carry bear spray, a very intense pepper spray and make sure it’s handy. “I can’t tell you the number of times I have seen people hunt for bear spray that they put in the bottom of their backpack. You see a bear, it sees you, it charges at you and you’re like, hold on, it’s in here somewhere. I know it’s here. Or did I leave it on the hook by the door?”

Protect Winnie & Smokey

And about those scary stories: while bear attacks get a lot of headlines, they’re rare. Globally, there are about 40 bear attacks on humans each year. In North America, between 2000 and 2017, there were 48 fatal attacks, with black bears causing a few more than grizzlies. Your chance of being attacked by a bear is roughly 1 in 2.1 million, which puts things in perspective. Most attacks happen because a bear feels threatened, not because they’re looking for trouble.

Two first-year cubs play in a meadow at Lake Clark National Park. A female bear can mate with more than one male during a single estrous cycle, so these cubs may have different fathers.

Sadly, humans are responsible for far more bear deaths. In December 2025, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission will allow the state’s population of 4,000 black bears to be thinned. Recently, 163,459 hunters applied for one of the 172 permits. Don’t despair if your name wasn’t selected. Florida also sells permits to cull alligators and pythons.

From the grizzlies of Alaska to the moon bears of Asia and the spectacled bears of the Andes, these animals are not just statistics or curiosities. They are integral to their wild homes, and their continued survival depends on our respecting their space, understanding their needs and appreciating the wild beauty they bring to our world.![]()

New York City based R.C. Staab is a book author, award-winning photographer, playwright, adventure traveler and wildlife enthusiast.This is his first story for the East-West News Service.