Tinsmith Jason Younis y Delgado demonstrates his craft to curious shoppers at the Traditional Spanish Market in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Photo courtesy of Tourism Santa Fe

Jason Younis y Delgado, fifth-generation tinsmith, sits at a table off the sunbaked plazuela of Casa San Ysidro in Corrales, New Mexico. The Casa is part of an historic adobe complex affiliated with the Albuquerque Museum. Surrounded by pieces of tin and rows of tools, he’s fabricating traditional tin works to sell at the casa’s annual harvest festival. Hammer, stamp, hammer, stamp. His hands move with precision around the curved edges of a piece of tin toward its heart-shaped center, which will hold a mirror. Unremarkable tin is being transformed into a work of intricate beauty.

The fine scallops he’s stamped around its edges, Jason notes, were once deemed too frilly for everyday items, but were a favorite of his grandmother, Angelina Delgado. In fact, every element of Jason’s creative process is tied to previous generations of his family. He holds a tool that looks like something a blacksmith rather than an artist might use. “This belonged to my great grandfather, Ildeberto Delgado.”

Exactly how tin art arrived in New Mexico is debated. Jason, 54, tells a story woven through his family history. It starts, he says, in the 1500s when Spanish silversmiths in Mexico traveled North on the Camino Real, a trail connecting Mexico City and Santa Fe. They hoped to make religious items for the new missions but found no sustainable supply of silver. So, they adapted their tools to work on leather, stamping intricate designs into saddles and other goods. Then in the 1800s, the U.S. army moved West with provisions packed in tin containers. Ever creative, the artisans adapted their tools again to snip and stamp tin, a metal that could be fashioned into practical items for churches and homes.

Andrew Connors, director of Albuquerque Museum, says there are other versions of the story, but most link the origin of New Mexico tinwork to the army’s arrival and creative entrepreneurs who repurposed its discarded tin. Connors says, family stories like Jason’s are important threads in the rich cultural fabric of the region. “His story is a perfect example of people in a remote community without many resources making decorative artifacts out of what might be considered trash by others.” An item in the museum’s collection even depicts part of the story. “We have a painting of old Albuquerque by a French artist who traveled here in 1885,” Connors says. “In the foreground is a large pile of dumped tin.”

Tools used by modern tinsmiths have changed little over the generations. Photo by Christine Loomis

Jason’s version may not be the only origin story of New Mexico tinwork, but it resonates because it speaks to what lies at the heart of this artform—creativity, adaptability, patience and an enduring passion to keep traditional skills alive.

Even in more recent times, tin artists have continued to adapt. Until the 20th century, the predominant metal used by tinsmiths was terne plate, tin-and-lead coated steel used primarily for roofing. “It was delicious, beautiful metal to use,” Jason says. “The minute you finished a piece it looked 200 years old. But it was banned because of the lead.”

Today, most tin artists use tin plate, a thin sheet of steel or iron coated with a bright layer of tin that resists rust and is very slow to tarnish.

For decades the knowledge and skill to create traditional tin art resided with just a handful of families of Spanish lineage—five, according to Jason. No one could learn or practice tin art unless accepted as an apprentice by a master tinsmith—nearly impossible for anyone outside of those families. Tools and techniques were as closely guarded as any family treasure.

At 13, Jason began apprenticing with his grandmother, who pursued her passion despite her father and grandfather’s initial refusal to let her apprentice, suggesting she learn “women’s work,” such as weaving, instead. Today, her tinwork is widely acclaimed.

For Angelina Delgado and the generations before her, tinwork was about strictly preserving family heritage and techniques. Not surprising, teenage Jason didn’t always see things her way. She once rejected over half of the candleholders he made to sell at a market; he demanded to know why his work had to be perfect.

Francisco Delgado working at his Canyon Road studio in Santa Fe sometime during the 1930s. Historic photo courtesy of New Mexico’s Palace of the Governors.

“I don’t expect you to be perfect,” she replied. “I expect what we sell to have the lineage of your great-great grandfather. There’s no Jason work. There’s no apprentice work. There’s only Delgado work.”

It was a high bar. Jason’s great-great grandfather, Francisco Delgado, was a preeminent tin artist whose work today is in the Nuevo Mexico Heritage Arts Museum and International Museum of Folk Art, both in Santa Fe. He was also one of the pioneering artists with a home and studio on Canyon Road in the early 1900s. He helped launch the road’s enduring identity as Santa Fe’s epicenter for art and artists.

Traditional New Mexico tinwork evolved in the northern cities of Santa Fe, the state’s capital, Albuquerque, the largest city and Taos, a small town 50 miles South of the Colorado border cradled by the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Much of the state’s tin art is still created, exhibited and collected in and around these northern cities.

The Nuevo Mexicano Heritage Arts Museum, formerly Museum of Spanish Colonial Arts, holds hundreds of traditional tin pieces. Jana Gottshalk, director and curator, says the name change was partly to move away from the word colonial and its negative connotations, but mostly because the museum now holds a much broader collection of pieces, ranging from 1825 to today. The word heritage is deliberate. “We call tinwork and other types of art here heritage arts because they’re living traditions,” she says.

Gottshalk credits the WPA for championing heritage arts in the 1930s. “The history of the WPA in New Mexico was incredibly art-driven in presenting traditional practices. Works created for WPA projects furnished federal buildings and schools; however, many were unsigned, so we don’t know who made them.” Records show that Delgados were among the WPA artisans.

To walk through the museum, housed in a historic home, is to walk through decades of tin art. A chandelier by Jason’s great-great grandfather hangs in one room, a mirror by his grandmother in another. The collection also includes whimsical pieces by contemporary artists of varying backgrounds.

Jason Delgado draws on generations of family heritage when he begins to craft a tin adornment. Photo by Christine Loomis

Jason chooses to work only in traditional forms and designs, but other artists have used tin in a variety of creative ways, which some traditionalists deem disrespectful. Gottshalk disagrees. “The fact that someone does something in a contemporary way isn’t by default disrespectful. Many of these artists know traditional ways but choose to expand.”

Jason calls expansion of the art critical to its survival. He teaches, once had a YouTube channel, sells punches to help novice artists get started and sells his art on Etsy. “Up until the 1980s, traditional tinwork was tightly controlled; no one outside the families was doing it. My generation realized expansion was important to keep the skills alive, but that it was also important to share our heritage and history. Anyone taking my classes leaves with an understanding of and respect for the history, families and culture.”

Jacob Gutierrez, 28, embraces the history and traditions of tinwork but his art is a contemporary expansion of those traditions. A New Mexico native, he began his art career as a printmaker, becoming interested in traditional tin art to frame his prints. With few “how-to” resources available, he cobbled together information by reading books and studying collections in the International Museum of Folk Art. Eventually, he simply bought metal and nails at Home Depot and began experimenting. He also bought several punches from Jason.

“The knowledge of tinwork is well-guarded; I respect that,” Jacob says. “The artform wasn’t gifted to me through family so I want to respect it as much as possible. I also want to adapt it.”

Jacob’s art is an amalgam of his heritage. His work at Lapis Room, a gallery in Old Town Albuquerque, is a visual intersecting of elements in his life. His prints might include traditional religious images and designs, but also ranch animals, especially cows, a nod to his family’s ranching heritage. Then there’s low-rider culture, the celebration of Mexican American culture centered around highly customized cars sporting vivid colors and elaborate detail work created in “candy paint.” His experiments with candy paint over tin are represented by a vibrantly red triptych mirror at Lapis Room priced at $1,200.

“Everything I do,” he says, “is about how much I love New Mexico.”

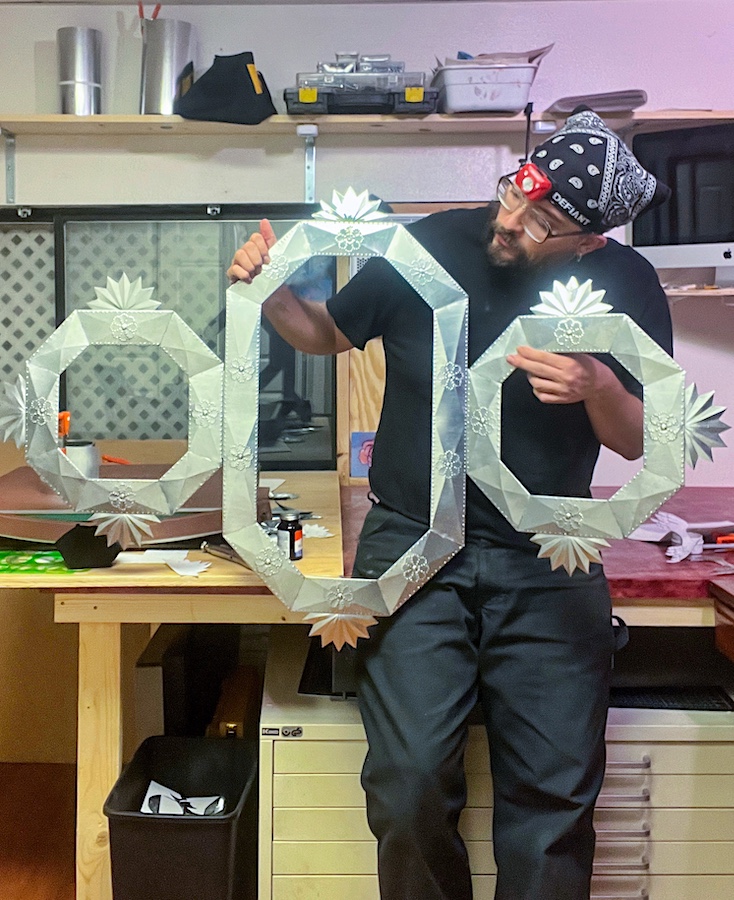

Jacob Gutierrez, 28, displays tin mirror frames destined for sale in Albuquerque. Photo courtesy of the Lapis Room Gallery

Heritage arts are highly valued in New Mexico. Tin evolved within Hispanic culture, but other cultures also produced heritage arts in the form of textiles, ceramics, straw applique, hide paintings and retablos (religious folk art). “There’s a complicated relationship between the Spanish, Mexican and Native cultures here,” says Meg Grgurich, deputy director of Lapis Room. “Many people from New Mexico share cultural heritage with both the ‘conquerors’ and the ‘conquered.’ Over the centuries, cultures have become intertwined; this is what makes heritage arts so special. They keep traditions alive and celebrate origin stories in a beautiful and meaningful way.”

Heritage arts also provide jobs. While there are no figures specific to tinwork, a recent study found that more than 5,000 people in the Albuquerque area are employed in artisan work, including tinwork. Markets also boost the economy. The 100-year-old Traditional Spanish Market in Santa Fe draws 20,000 people from the U.S. and beyond over one July weekend to see and buy Hispanic heritage arts, tin art prominent among them.

The Nuevo Mexico Heritage Arts Museum displays tin art created over the past 200 years. Photo by Christine Loomis

Artistically inclined visitors to New Mexico’s capital and largest city will see small tin ornaments, frames and mirrors in shops and markets. The items may look easy to manufacture and similar to the mass produced, machine-cut tin ornaments from Mexico. They are neither. Traditional New Mexico tin artists spend years learning the skills to create them. “It’s easy to walk by them and not understand the depth, authenticity and family these pieces represent,” Jason says. “In my case, my work represents hundreds of hours apprenticing with my grandmother. It represents my great grandfather and great-great grandfather.”

Every piece Jason creates is an expression of love for his art and this place where his family has lived for over a century. “My single greatest joy and the reason I’ve been able to do tin work for a lifetime and still enjoy it is that it’s a beautifully complex connection to my family. As I work, I’m touching tools that touched all the previous generations. Even the tinsnips my grandmother left me have her name engraved on them. I think of her every time I use them.”

He worries about the future of the art he loves. “If there were a federal endangered list for folk arts, we’d be on it.” He hopes one of his children will carry on the Delgado tradition but knows that may never be. “They fool around with it but don’t do the real work. I did it because I wanted to and it was a joy and is still a joy…We’ll see,” he says, stamping the final flourish onto the piece he’s been working. Fittingly, it’s a sacred heart.

Going to New Mexico? Here’s Where to stay, eat and see tinwork

ALBUQUERQUE

Opened in 1939 by New Mexico native Conrad Hilton, historic Hotel Andaluz Albuquerque has been meticulously restored with its beamed wood ceilings, brickwork and traditional Andalucian archways framing public spaces. Grab a coffee around the corner at friendly Moka Joe’s Coffee.

At family-owned Golden Crown Panaderia, the baked goods and ice cream are house-made, the coffee roasted onsite. Must-tries: pizza with green-chile crust, biscochito (New Mexico’s official state cookie) and a tasty coffee milkshake.

Mesa Provisions: A James Beard Foundation nominee serves upscale southwest-inspired fare such as a smoked beet tostada with pecan salsa macha and red-chile braised short ribs.

In 2029, New Mexico will celebrate 400 years of winemaking. Get a head start at Noisy Water Winery in Old Town Albuquerque. Wines are produced from regions across the state, and many have won medals in national and international competitions, including the 2021 Reserve Pinot Noir and 2023 Besito Caliente Chile Wine.

Lapis Room: Ninety percent of the artwork is by New Mexico artists. Look for Menagerie, a mobile by Kevin Pierce ($650), contemporary paintings by Beedallo ($1,800-$4,000), pendants by jeweler Kristin Diener ($95-$3,200) and the striking candy-paint-over-tin Guardian Angel Triptych by Jacob Gutierrez ($1,200).

Jason Younis y Delgado. Find him here at his Etsy shop or on Instagram at Metalsmytheshop.

SANTA FE

Nuevo Mexicano Heritage Arts Museum and International Museum of Folk Art on Museum Hill offer perspective on the state’s historic and contemporary arts, including religious artifacts, sculptures, New Mexico folk-art embroidery, jewelry, paintings, furniture and more. Book lunch at superb Museum Hill Café, where corn custard and fresh grilled salmon salad are highlights.

Traditional Spanish Market. Peruse the work of many Spanish heritage artists at the summer market, July 24-26, 2026.

Fred Ray Lopez Tin Works: Lopez, who studied with Angelina Delgado, sells traditional and contemporary tinwork, including tin combined with weaving or reverse-glass painting, as well as gold and silver jewelry, in his Santa Fe Village studio/shop.

Christine Loomis is a Colorado-based freelance journalist who covers travel, hospitality and lifestyle subjects for regional, national, print and digital publications. This is her first article for the East-West News Service.