Argentine gauchos work the northern Gran Chaco as well as the Pampas to the south and embody the proud history of Salta.

By Nancy Wigston

Argentines know it as Salta la Linda “the beautiful one.” Situated 3,400-ft above sea level in the De Lerma Valley of Northern Argentina, the city of Salta (pop 620,000) reigns in splendid isolation. Chile lies to the west, Bolivia to the north, and Paraguay to the east. But between Salta and Paraguay lies the Gran Chaco, an undulating, semi-arid expanse of savannah more than twice the size of California that is covered by a massive forest second in size only to Brazil’s Amazon rainforest.

In 1582, Philip II ruled Spain and conquistador Hernando de Lerma founded Salta to link Lima and Buenos Aires. De Lerma hailed from Seville in Andalusia, and Spaniards today claim to recognize the Andalusian style in the old metropolis.

Andalusian or not, a singularly pleasant mood pervades the air in Salta, a kind of easy timelessness. Strangers are friendly, foreign tourists few. “I love your hat! It’s beautiful!” said a woman in Spanish, switching to English when she saw the puzzled look on my face. Overhearing a snatch of English conversation, a man stopped two tourists. What was meant by “mental image?” They explained and later asked if he was happy? “A little happy, not very happy, but a little happy,” came the cheerful response. People here seem a little happy most of the time.

Perhaps the best place to start your Salta adventure is the spectacular 16th century plaza, The 9th of July, named for Argentina’s Independence Day. With its palms, red flowering ceibos (the national tree), purple jacaranda and fruit-bearing orange trees, this oasis in the heart of town is both elegant and lively. Under a sliver of the new moon, folks were hanging out on benches near the grand 1908 fountain, as bands played folk music, magicians did card tricks, old-style dancers performed their timeless steps. Moving smoothly through the crowd, vendors offered glasses of fresh fruit juice from trays. Anchoring the square, fifteen feminine statues—one for each Argentinian province plus one for Lady Liberty—encircle revolutionary fighter and Salta governor Juan Antonio Alavarez de Arenales, who sits regally astride his horse.

Church of San Francisco at night in downtown Salta is typical of the Baroque style employed in Northern Argentina. Originally constructed in 1625, the church was rebuilt in 1759 following a fire.

Across from the square is the 18th century Italian Baroque-style rose-and-cream Cathedral with its Corinthian columns. Close by is El Cabildo, an 18th century town hall turned history museum, rich with furniture and paintings that evoke the wealth of colonial days. In the same row you’ll find the Archeological Museum of the High Andes, a small, very popular museum dedicated to the startling 1999 discovery of mummified Incan children by archeologist Johan Reinhard. At the 22,000-ft summit of volcanic Mt. Llullaillaco, Reinhard unearthed three graves more than 500 years old.

The Children of Llullaillaco are dressed in Incan finery, their funerary goods of silver, gold and obsidian displayed nearby. These specially chosen children were ceremonially drugged, buried, and left to freeze. As a result, their skin, hair, clothes and internal organs are largely intact, and, as clichéd as it sounds, they appear to be peacefully sleeping. Child sacrifices were important rituals during the centuries that the Incans ruled much of Central and South America, an empire that collapsed when Spaniards subdued Peru in the early 1500s.

Important battles for independence from Spain were fought and won in the north. Salta-born caudillo Martin Miguel de Güemes, famed for guerilla warfare, was admired by anti-royalist Generals José de San Martin and Manuel Belgrano and remains a local hero. Güemes’ exploits are celebrated in a museum, at 730 Español, a few blocks from the plaza. His statue adorns a park below the hill of San Bernardo, on the spot where he received a fatal wound. The summit of the 935-ft high hill can be reached by road or by Swiss-made cable car, and makes an ideal spot for picnics, craft market shopping, or drinking in views of the chessboard-like city below.

Agriculture has always been important to Salta’s economic health. The province produces tobacco, grapes, lumber, sugar, and corn. Wines are produced southeast of the city. Tourism, too, is on the rise. One cautionary note: visitors from more stable economies than Argentina’s may find money exchanges in Salta somewhat bizarre. Cash is used a lot, mainly by locals, and you see unusually large stacks of paper money, even in electronics stores. Street market vendors take cash, but shops selling fine silver, woollens, and leather goods accept credit, as do the better restaurants. You’ll be charged about 3% for using credit cards. Naturally, everyone takes cash—but best not to carry too much on your person.

The rose and cream-colored cathedral in Salta looks out on the city’s 16th Century plaza.

Salteños tend to be traditionalists, proud of their history. Gaucho-outfitted waiters at Doña Salta Restaurant on Cordoba 46 serve the best cheese empanadas in town as well as goat and rabbit stews and fresh corn tamales. The dishes reflect a culture with close ties to the original colonizers. Twenty per cent claim criollos descent, from the Spanish conquerors. Indigenous peoples and mestizos–offspring of Spanish and Amerindians–form the largest population group, trailed by immigrants from Turkey and the Middle East, with fewer Italians than in the south.

Still, pizza is everywhere. Salteños aren’t stodgy. At family-owned Fili Helados, in a chic Art Deco building at 299 Avenida Sarmiento, you’ll not only find the best Dulce de leche ice cream in town, but innovations like wine-infused gelatos. Malbec gelato? An acquired taste.

As for nightlife, tango is not unknown in the north, but the entertainment called peña scores much higher on Salta’s must-see list. For a real taste of northern traditions, head to Calle Balcarce, the city’s nightlife hub, alive with bars, restaurants and peña supper clubs. One of the best is Pena el Vieja Estacion, housed in a former train station. Mains include empanadas, llama stew, steak, and house reds and whites. More dazzling than the food, however, is the folkloric stage show: booted gauchos leap about the stage, sing old songs, perform rope tricks, and share the floor with equally energetic ladies dressed like Miss Kitty from Gunsmoke. Guitars and drums accompany the engaging–and very loud–performance. Audience members—especially men and boys—vigorously join in with the region’s greatest hits. A peña evening is all about tradition and exuberance. Not to be missed.

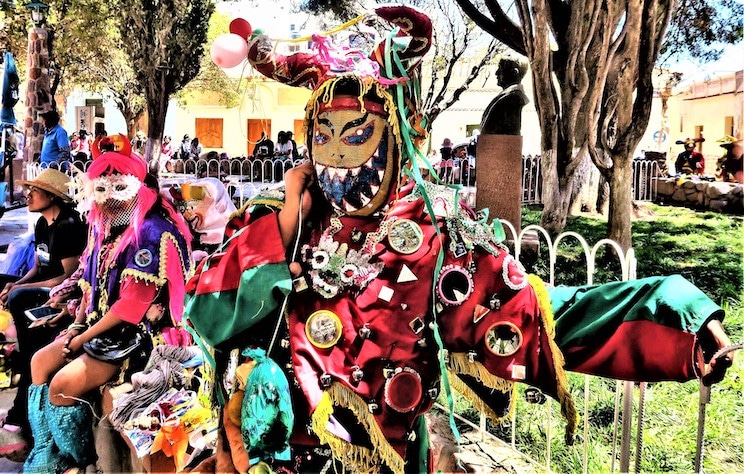

Even little devils dressed for carnival are happy most of the time

Most visitors to Argentina’s Andean regions rest a while in “the beautiful one,” easing into the altitude, before tackling higher and more remote geography. Accordingly, after three days, we depart Salta early one morning to continue the adventure in an all-terrain vehicle driven by English speaking guide Javier Lopez. He’s taking us on “the circle route” that goes west toward Chile before heading north and looping back to Salta. Javier’s English is excellent, thanks to college courses, and he’s good at sharing lore about the pre-Incan tribes who once lived hereabouts. He stops frequently so we can examine giant flowering cacti that can live a hundred years.

Mostly this is arid desert, broken only by cacti, the odd roadside shrine to the Virgin Mary, or the occasional rock mound (apacheta) indicating the road’s highest point. Then Javier pulls up under a gigantic black train trestle above the Toro Gorge. Hills hundreds of feet high glow golden in the morning sun. The road climbs steadily upward and despite this being summer, a light sweater or jacket often is necessary. Remote Andean towns average 60 degrees on February afternoons; temperatures plunging dramatically in winter.

A continental breakfast of coffee and the rolls called mesalunas awaits at El Alfarcito, a clutch of pretty white adobe buildings–church, school, café and gift shop—the legacy of beloved “Padre Chifri” a Jesuit priest from Buenos Aires with movie-star good looks. He devoted his life to educating mountain children and everything the padre created here speaks of quality, including the goods for sale in the shop. A cut above the usual tourist tchotchkes, these woollen ponchos, handmade toys, and leather goods deserve a second look. Outside, a lofty but adorable llama poses for photos. I mentally cross llama stew off the menu.

After stocking up on empanadas at a bakery in San Antonio de los Cobres, we head for the train station, where Javier lets us off among the souvenir hawkers and day-trippers. The mountain air bursts with anticipation and excitement, as we board the hour-long Train to the Clouds, a narrow-gauge train line launched in 1948 that ranks fifth highest in the world.

The Train to the Clouds rumbles across Al Polvorilla Viaduct at an elevation of 13,850-ft. Onygen is available if needed but most passengers get by with coca tea and chewing dried coca leaves.

Before boarding I spot a sad-looking girl with her meagre offerings, so I impulsively give her 15 pesos, wanting to cheer her up. But her train attendant friend pipes up, in English. “She’s not sad, she just wants love!” “Oh,” I reply, “Don’t we all?” At which all three of us laugh and I take her picture, looking happy and smiling. Such is the mood in the mountains.

Onboard, in the “English car,” we look west toward the Andes, the natural border with Chile. Many of the formidable looking mountain peaks are topped with snow. Above us are skies the bluest of blues, dotted with white cottony clouds. The “clouds” in the train’s name refer to white vapour trails streaming behind the old steam locomotive, filmed by students in the early 1960s on a travel adventure they named “Train to the Clouds.” The moniker stuck. Today’s tourists can thank recurring rock falls on the lower tracks from Salta for this one-hour “heritage” route.

Painted mountains in the Quebrada de Humahuaca

Towering peaks outside the windows give way to vast empty-seeming valleys, the high desert called la puna, a kind of pumpkin-color. Since our train reaches breathtaking (in a literal sense) heights of 13,850 feet, many passengers dutifully chew handfuls of dried coca leaves—like bay leaves, but smaller. They taste much as you’d expect: bitter. More palatable are free cups of coca tea in the snack bar (lavishly sweetened with sugar) and coca candies, which are delicious despite their lurid green color. Walking through the train to fetch cups of tea, I notice several large oxygen tanks and nod to the friendly onboard medic. (No one needed oxygen that day, no one seemed ill.)

Our cheerful English-speaking guide introduces the train’s history to a gaggle of Russians, Germans, Norwegians and North Americans. We chat, bonds form. When the guide dramatically announces that we’ve reached “a miracle of Argentinian engineering,” the climactic La Polvorilla Viaduct, everyone pays attention. Constructed during 1930-32, it rests on six pillars at 2.60 miles above sea level. Cameras appear, passengers snap away. As the man from Russia leans out an open window, braving heights and thin air for the best shot, his neighbors exchange nervous glances.

Euphoric from the heights, we arrive at the next and final station, where Javier meets us with the car. Most excursions from Salta include our next stop, at the dazzling “white desert” of Salinas Grandes, shimmering salt flats a short but bumpy ride away. The sun flashes over endless blue waters, mounds of white salt, and some curious mud-coloured structures (Including a giant-sized llama). The salt and the blinding sun produce an odd effect: people become playful, giddy, take staged photos.

Pre-Lenten Carnival in the mountain village of Humahuaca’s central plaza gives devils-may-care celebrants a chance to have fun

After leaving Salinas Grandes, half-blinded, our road trip resumes. “Now the show starts,” announces Javier. What show? He means nature, miles of nothing but deep valleys, herds of domesticated llamas, cows, goats, and flocks of wild vicunas. In the village of Purmamarca (pop: 2008), we happen on the annual pre-Lenten Carnival (mid Feb-March). Celebrants are laughing madly while splashing one another with tortilla flour. Local bands rock the dance hall, tourists in their summer clothes join in, dancing with locals wearing horns and devils’ masks. Clearly the devils are having a blast before they return to hell, whereas the flour-splattered tourists seem a tad nervous.

Street vendor in Purmamarca enjoys the carnival while waiting for customers

Next day, after a night at an environmentally friendly hotel, a power outage, a nine-o’clock supper (Spanish tradition) and an immense, starry night, Javier arrives to tour us through the narrow valley of Quebradade de Humahuaca, a UNESCO Heritage site since 2003, and a trade route for ten thousand years before that. This is nature’s show: painted mountains, accordion-pleated mountains, Seven Color mountains, Bolivian Skirt mountains in colors of ochre, crimson, and green.

Nearly as colorful as those mountains are the people of Humahuaca (pop: 11,269). At midday, costumed crowds gather in a leafy plaza under a white-towered church. Exactly at noon, two doors open halfway up the tower, under the bell. A mechanical figure representing San Francisco Solanos (German-made, 1840) slowly emerges. Raising his right hand in blessing, with his left he raises a cross. Having blessed the crowd, the saint retreats inside his tower while a tinny version of Ave Maria blasts from the church across the way. As the doors close behind him there’s a round of applause. On this last day of Carnival, many of the faithful are costumed as devils, which is not a contradiction in the mountains, where the old earth-centered religion coexists with Catholicism, especially during Carnival.

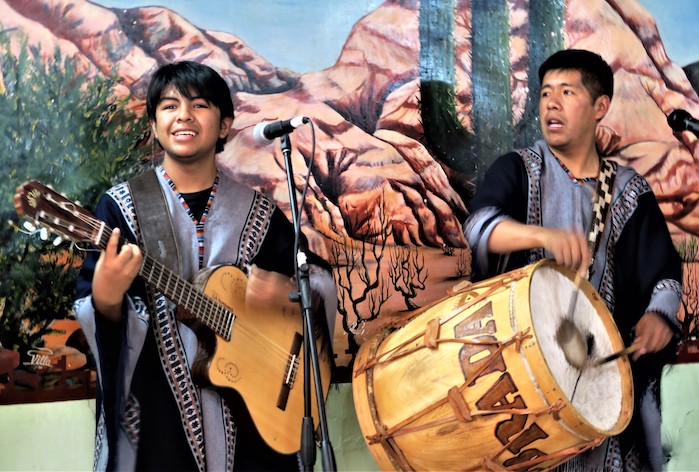

Humahuaca is quirky, splendid with life: a mechanical saint, charming devils, strong coffee in clay cups, presented on purple cloth. And the topper, lunch at La Cacharpaya, a restaurant at 293 Humahuaca, that features enormous portions of hot roast chicken, delicious papas fritas and homemade flan plus a band that appears just as soporific indulgence sets in. A man plays a ukulele-like guitar; another strums a regular guitar; a third beats a giant drum, and most beautifully, a fourth plays the Andean flute. In no time the place is rocking, diners clapping along with the beat, a real party. Entranced by the music, two young trekkers, in shorts and t-shirts, seat themselves in the window, warmed by the blazing sun. A young devil wanders inside.

Andean band at La Cacharpaya restaurant in Humahuaca spreads the carnival spirit

If You Go: Many travel agents in Salta offer day or overnight trips that include the train ride, the salt flats, and stops in a variety of towns. Prone to altitude sickness? Consult your doctor before travel. No one on our train needed emergency oxygen, but some travelers came armed in advance with physician-prescribed medicines.

Nancy Wigston is an award-winning travel writer whose work has appeared in England, South East Asia and her native Canada