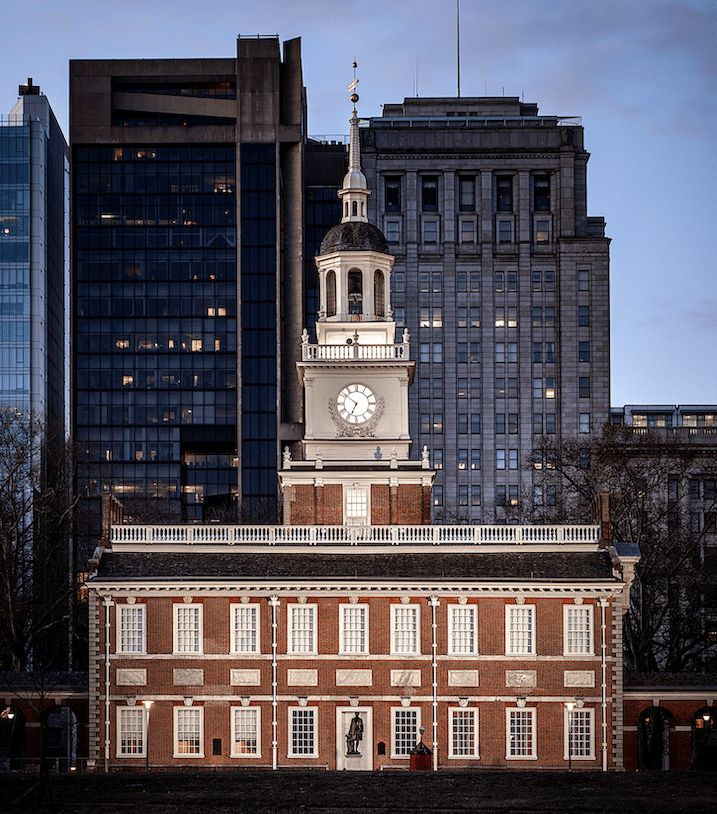

Old and New Philadelphia. Built in 1747, Independence Hall has been the focal point of Philadelphia for 275 years. Oblivious to the surrounding high rise office buildings, people from all over the world line up to walk through the diminutive chambers were history was made.

By Rich Grant

It’s become fashionable of late to denigrate America’s founding fathers. Old white guys. Plantation owners. Colonialists who only started the country to keep slavery legal. Viewing America’s history through today’s woke prism, however, ignores the genius of George Washington who, though buried in Virginia, maintains a lasting, living presence in the city of Brotherly Love.

Almost all of the important moments in our nation’s early history involve George Washington and, surprisingly, they all occurred in and around Philadelphia. In 1776, Philadelphia was, after London, the second largest city in the British Empire with a population of 40,000 people and 6,000 impressive brick buildings. Miraculously, 2,000 of those 18th century structures still survive.

That means today’s downtown Philadelphia is America’s most European-looking city. If you can’t go to Europe any time soon, come here to enjoy a city of cobblestone streets, beautiful squares with wood benches, old churches with quiet graveyards, cozy taverns lit by candles, flickering gas lamps and an overwhelming sense of history.

Philadelphia was George Washington’s favorite city. He lived here for years and practically everything important in his life took place in or around this town. So who better to be our guide? Let’s follow George around to visit some Philadelphia historical sites.

Independence Hall

Where better to start than the most important building in early American history? It was here in May 1775, after the battles of Lexington and Concord, in the midst of a violent revolution, that the Continental Congress appointed George Washington as commander in chief of America’s first army. He began this military career with a self-effacing speech that you rarely hear in the 21st century, telling Congress, “I, this day, declare with the utmost sincerity, I do not think myself equal to the command.”

Master Carpenter Edmund Woolley had built the hall in 1747 for Pennsylvania’s colonial government. Because it was the largest building in the largest city in the colonies, it became the site for the Second Continental Congress. The Declaration of Independence was approved here in July 1776 and Washington presided over the Constitutional Convention held here in 1787.

Today, the room is laid out as it was when the Constitution was created, with the chairs of the 55 delegates in a semi-circle facing the actual chair in which Washington sat. We tend to focus on 1776 as the birth of America, but the country’s real future began in 1787 when 55 delegates filed into this room. You can go in the same door and stand on the same floorboards. Seldom in history has such a small room held such men.

America’s Declaration of Independence was signed in this room in 1776. Eleven years later, the modest chamber witnessed the signing of the U.S. Constitution. Fifty-five delegates lead by George Washington, who became the country’s first president two years later, created a democratic government that has lasted more than 230 years.

Beside Washington, there was Alexander Hamilton, Ben Franklin and James Madison. These 55 delegates would supply America with 2 presidents, 3 cabinet members, 16 U.S. senators, 11 House members, and four Supreme Court justices. All of them had been involved in the revolution; 23 fought as soldiers. No matter what your political beliefs today, to stand in this room is an historic moment everyone should experience. I was so moved, I came back later in the evening at twilight to walk around the building.

The delegates met here from May 25 to September 17, 1787, with the daunting task of creating a new form of government “of the people, by the people and for the people.” Democracy. In the world of 1787 the concept didn’t even exist.

To prevent “leaks,” the shutters were drawn and the room was swelteringly hot. They argued, debated, yelled, fought, made compromises followed by long speeches and then argued some more. A dozen of them owned slaves, and slavery was a huge issue. Those from smaller states wanted to preserve their influence; those from larger states wanted more power. They feared traitors and, if truth be told, they actually feared true democracy. In a land where few were educated, majority rule might easily become mob rule. But as it got hotter in August, the speeches grew shorter and the compromises more frequent.

We can’t know what these delegates might think of America today; we do know what they thought of the Constitution they eventually signed. They were mostly disappointed. To them, the document was a series of compromises. Each delegate may have won a few battles, but lost many others. The public greeted it with the same lack of enthusiasm, even when the Bill of Rights was added.

The delegates could not possibly imagine they were creating what would become the oldest written government constitution in the world, a document that would inspire more than 700 other constitutions in 200 other nations.

As the delegates left the hall for the final time, a lady in the crowd shouted out to Ben Franklin, “Doctor, what have we got? A republic or a monarchy?” to which Franklin supposedly responded, “A republic, if you can keep it.” And then they all went to City Tavern.

City Tavern

It’s a pleasant 5-minute walk from Independence Hall to my favorite colonial tavern. John Adams called it “the most genteel tavern in America.” We can only assume he meant “refined, respectable, polished, proper and polite.”

City Tavern has a front door, but I prefer to approach it from the rear, getting off Chestnut Street and walking through Liberty Square, past Independence Hall and Carpenter Hall, strolling through a quiet park, while slowly leaving the modern world behind. Continue past the First Bank of the United States to Dock Street where you’ll come upon your first view of the tavern sign and the pub’s backyard. Entering through the backdoor takes you immediately to City Tavern’s bar, where history comes with cold beer.

After signing the Constitution, all of the to the Constitutional Convention headed to City Tavern to celebrate. At lunch or dinner you can select from the same bill of fare they enjoyed back in the 18th century.

Colonial taverns were municipal nerve centers. A “subscription room” in City Tavern had all the newspapers of the day and men gathered here in a room filled with tobacco smoke and politics to read and discuss the latest events. It was the Facebook of 1776.

Paul Revere rode to City Tavern from Boston in 1775 to bring the news of fighting at Lexington and Concord. While drafting the Constitution in 1789, George Washington dined here often. So did most of the other delegates. On the day they finally finished writing the Constitution, Sept. 14, 1787, Washington and 54 other gentlemen gathered here and consumed seven bowls of rum punch, eight bottles of cider, 34 bottles of beer, 54 bottles of Madeira and 60 bottles of French Bordeaux. Today, their bar tab would be $15,400.

In the 21st century when people argue about the Constitution and what the Founders meant, there is one point no one can argue: The intent of the Founding Fathers on Sept. 14, 1787, was to get blitzed.

After all that drinking, what did they eat? Beef, chicken, hams, baked oysters, lamb, game and all varieties of fish were available. Banquets could offer up to 140 different selections. Liquor, coffee, tea and ice cream were popular. Everyone drank beer and hard cider because they were much safer to consume than water.

City Tavern still serves historic ales that include General Washington’s Tavern Porter, brewed from a genuine recipe of the General’s on file in the Rare Manuscripts Room of the New York Public Library; Thomas Jefferson’s 1774 Tavern Ale, a beer he served at Monticello; and Poor Richard’s Tavern Spruce, based on a recipe Benjamin Franklin concocted before becoming ambassador to France.

They all taste terrible and are overpriced, but how often can you drink history? You may forget a thousand beers you drink in your life, but you will never forget these, served in this setting.

The first City Tavern fell into disrepair and was torn down in 1854. Working from the original plans, the National Park Service built an exact replica in 1975. Is it touristy? Yes. Expensive? A bit. But the tavern serves a colonial inspired menu, waiters and waitresses dress in 18th century attire and the dining rooms are lit by candlelight.

Museum of the American Revolution

A block from the tavern is a museum that tells a different story about the Revolution than you learned in school. 1776 was a nasty year that makes today’s political divisiveness look rather tame.

At the start of the revolution, there were two million colonialists living in North America – a third were rebels, another third were loyal to the king. The final third just wished the whole thing would go away. Also here were another million souls caught up in the war without any choice. They were enslaved Africans. who made up one out of five people on the continent.

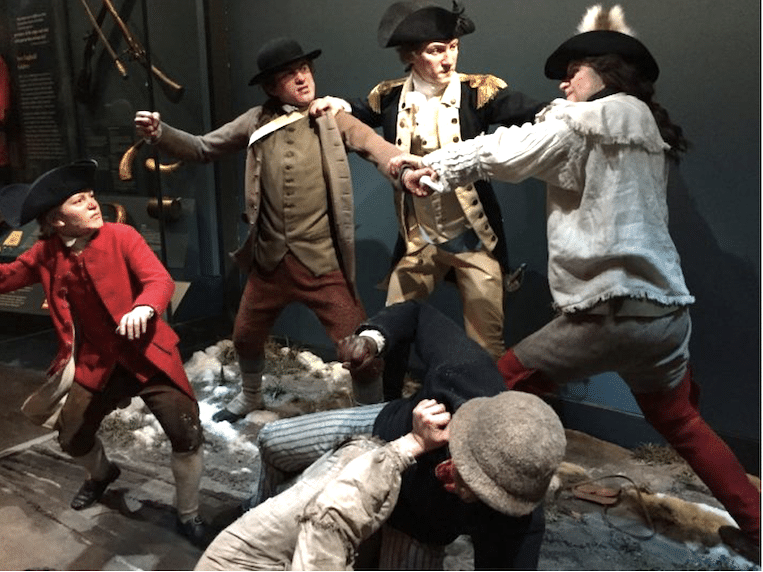

One of the more intriguing exhibits in Philadelphia’s Museum of the American Revolution shows George Washington breaking up a snowball fight between some of his soldiers. The winter frolic occurred at Harvard in 1775. The revolution Washington would lead was still one year away. Harvard University at that time was already 139 years old.

It was a brutal civil war. England sent the largest armada of ships and professional fighting men the world had ever seen. Washington had a rag tag army that spent more time retreating than fighting. But colonial soldiers stopped running away long enough to counterattack at Trenton and Princeton on Christmas 1776; both these battlefields are just 40 minutes from Philadelphia and are given major attention at the museum.

The museum has some unusual exhibits. One is a life-size diorama of a 1775 snowball fight at Harvard in Boston. Apparently, Washington was outraged his soldiers were fighting each other with snowballs and jumped into the fray to tear them apart. There’s George in the middle of the fray, life-size and in full-rig uniform with gold epaulets, swinging fists with the best of them.

Elfreth’s Alley

What did colonial Philadelphia really look like? If you walk a few blocks from the Revolutionary War Museum to Elfreth’s Alley, you can see. This is the oldest continuously inhabited street in America. The 16-foot-wide cobblestone alley is lined with 32 brick rowhouses built between 1728 and 1836. It is incredibly picturesque. Originally, these were the homes of grocers, shoemakers, tailors and other tradesmen who worked on the bottom floor and lived above. Today, they are private houses, but two built in 1755 operate as a small museum providing a glimpse of colonial city life. The alley probably didn’t look this pretty in the 19th century, but today, it can hold its own with any quaint backstreet in Europe.

To see what Philadelphia looked like during the American Revolution take a stroll down Elfreth’s Alley.

George Washington marched his army down this street in 1777 en route to the Battle of Brandywine (he lost that one). It is easy to tell which houses were here at that time. Homes from the revolutionary era had front doors that opened directly onto the street. Because the streets were filthy, the stoop was invented later in the 19th century with doors that opened a foot above street level onto a stone block.

Betsy Ross House

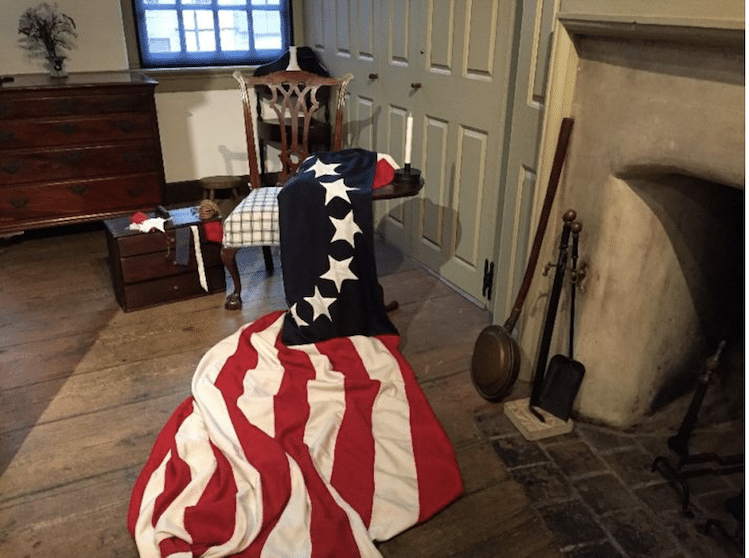

As the legend goes, George Washington once visited Betsy Ross’s house, and since it was only a block away, I did too. George allegedly asked her to make the nation’s first flag, the one with 13 white stars in a circle on a blue field with red and white stripes. Betsy suggested using five point stars instead of six, and she showed George how it was easier to cut them. That last part about cutting stars is true, and living historians at the house delight in showing you an easy way to cut perfect five point stars.

For the rest? Well, it could be true. George did know Betsy Ross and had hired her as a seamstress. She did sew flags for the U.S. Navy. She might have lived here, but probably she lived next door. It really doesn’t matter — the house was built in 1740, is authentic and was at one time a tavern! Altogether, it’s a great piece of Americana, even if the legend didn’t start until one hundred years later in 1876.

You get to wander around the house, climb narrow stairs and meet living historians. In the basement, I met Phillis, a free black woman who worked as a laundress. When you hear how hard it was to wash clothes back then you can see why most people didn’t mind dirty clothes.

Historical actors working at the Betsy Ross house will explain how the Philadelphia seamstress and George Washington designed the first U.S. flag.

George Washington’s House

George Washington’s house in Philadelphia was located almost on the front lawn of Independence Hall. It served as the first “White House” from 1790-1800, with President John Adams also living here Incredibly, the house was torn down in 1954 and a public toilet was built on the foundation.

Even that is now gone, replaced with an exhibit that shows the outline frame of the original house. But rather than celebrating the presidents who lived here, the exhibit tells the story of the eight enslaved Africans that Washington brought with him.

George was not perfect. He and Martha Washington owned 315 human beings, the sixth largest number of enslaved people in Virginia. When he came to Philadelphia as President, he brought his favorite chef, Hercules, Martha’s favorite personal servant, Ona Judge, and six others to run his household. There was one problem. Pennsylvania was a free state – any enslaved person living here for six months would be free.

Washington knew that, and meant to shuffle his workers in and out. However, both Hercules and Ona Judge learned of this law and instead of being “shuffled” decided to run away.

If the complexity of American history intrigues you, then keep walking another block through the park to the next stop, which will completely blow your mind.

The National Constitution Center

Located at the far end of the long Mall facing Independence Hall may be the most important museum in the nation. Architecturally, it’s not much, but inside it offers one of the most emotional experiences you will ever have.

It starts with a multimedia show that tries to explain how strangely wonderful and revolutionary the five pages of the Constitution were to the world in 1787, when for the first time in history a government statement began with the simple words, “We the People…”

It is the challenge of this museum to explain how over time, America has tried to enlarge, redefine and rewrite in law those three words.

Here you discover that the United States has one of only three constitutions on the planet that protects the right “to keep and bear arms.” That America offers far fewer protections of liberty than many other industrial nations is not hidden. But you also learn the magic of those five pages written more than 200 years ago and amended only two dozen times that have guided this country through so many challenges.

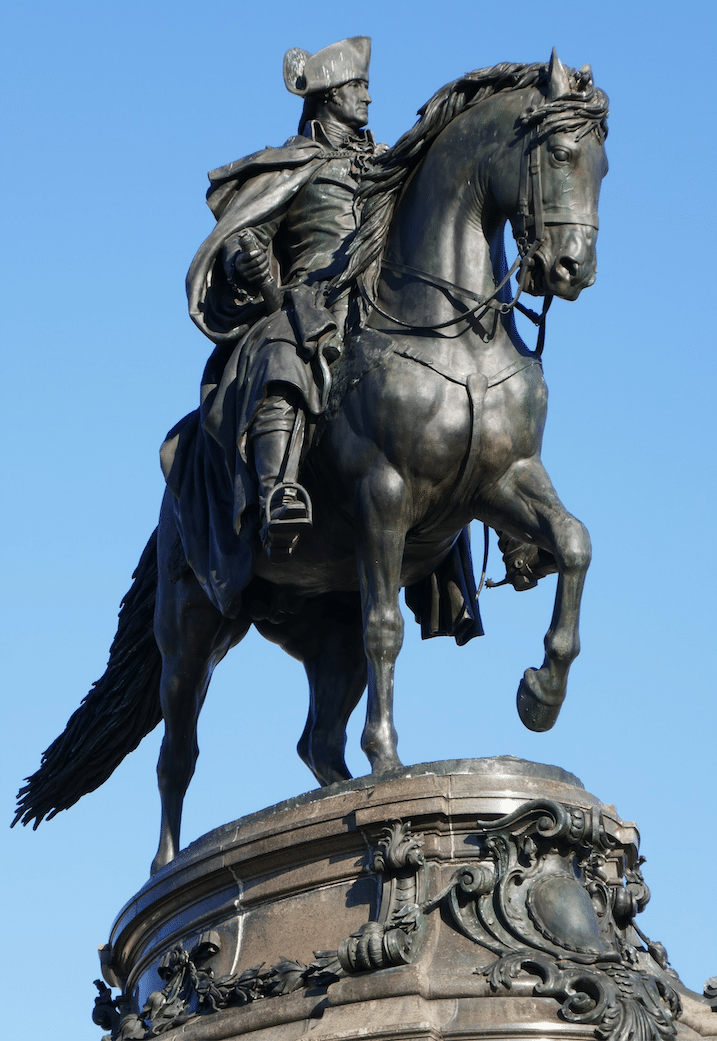

In 1776, Philadelphia was the second largest city in the British Empire. Today it is the sixth largest city in America. Washington still stands watch over the city from atop his monument at the northwest end of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in front of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

This museum points out that many of the problems confronting America do not stem from a five-page Constitution written two centuries ago but may result from the fact U.S. citizens have not taken the time to understand the document, and, as George Washington and our Founders intended, made the effort to continually update it. Visiting Philadelphia, to see where our country was born and where it may need to change, is one great step in the right direction.

Denver writer Rich Grant, whose last story for EWNS was on Deadwood, South Dakota, is a member of the Society of American Travel Writers and the North American Travel Journalists Association. He is the co-author, with Irene Rawlings, of “100 Things to Do in Denver Before You Die,” published by Reedy Press in 2016.