San Francisco’s Chinatown is the oldest Chinatown in North America. Since its establishment in 1848, it has been highly important and influential in the history and culture of ethnic Chinese immigrants to North America. It continues to retain its own customs, languages, places of worship, and social clubs. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress

By Mark Orwoll

In April 1904, Chinese Prince Pu Lun, the 32-year-old heir apparent to the throne of the Manchu Empire, sailed in luxury on the S.S. Gaelic for his first visit to the United States, accompanied by four secretaries, two bodyguards, two barbers, and four servants. Speeding across the Pacific at 15 knots, the Gaelic was the pride of the Occidental & Oriental Steamship Co.

Pu Lun, a clear-complected, clean-shaven young man, was fully aware that he would be the first member of the Qing Dynasty ever to cross the seas. He was a “Kodak fiend” who developed his own photos and was fascinated by everything he saw in America, forever asking questions about the plant life, the names of local fish and the history of this town or that village.

Acting on behalf of his uncle, the Guangxu Emperor, the affable young royal was en route to the St. Louis World’s Fair as China’s Imperial Commissioner of the Exposition. Along the way, he posed for pictures with government officials, visited local Chinese American dignitaries, and dined at grand luncheons and dinners full of VIPs eager to impress him—in Honolulu, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., and St. Louis. At one such banquet, the host knowingly set before Pu Lun a dish that he hoped would remind the young prince of home.

Prince Pu Lun, resplendent in his bright yellow silk robes and headdress with a three-eyed peacock feather, looked at the platter curiously and asked his host what it was.

“Why, that’s chop suey, Prince,” said the American.

Prince Pu Lun, ever eager to discover something new and foreign, smiled at this revelation, nodded his head slowly, and asked, “What is…chop suey?”

Qing Dynasty Prince Pu Lun (left) at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

IS CHOP SUEY CHINESE OR NOT?

Almost immediately afterward, a character named Lem Sen, who had traveled from the Bay Area of California to New York, announced that he planned to sue everyone who had ever made, eaten, or possibly even thought of chop suey. He held the patent, he stated, and he wanted his royalties. He claimed that he’d invented the dish 10 years earlier in a “bohemian” restaurant in San Francisco, specifically for his Western customers. The New York Mail supported Mr. Lem—at least insofar as chop suey’s origins were concerned.

“It must be explained first of all,” wrote the Mail, “that chop suey is not a Chinese dish…. It is a San Francisco invention, or rather adaptation; it is like an Irish stew translated into Chinese purely for Occidental degustation.”

The newspaper exposé, which shattered the illusions of thousands of chop-suey-lovers, appeared in dozens of newspapers across America. What’s next, everyone must have wondered? Soon you’ll be telling us that chow mein and egg foo yung aren’t Chinese either!

In the years since Lem Sen threatened his lawsuit (later withdrawn) and Prince Pu Lun expressed his perplexity at the dish, anthropologists and food historians have traced the origins of chop suey to Guangdong (Canton) province, which was a hotbed of Chinese emigration in the 19th century. Translated, the phrase means “odds and ends, assorted pieces.” In other words, whatever the chef can find in the larder. It’s not a Chinese recipe any more than “leftovers” are an American one.

“Chop suey is not a Chinese dish that you can find in China,” says Zai Liang, Distinguished Professor of Sociology at the University of Albany, SUNY, and the author of From Chinatown to Every Town: How Chinese Immigrants Have Expanded the Restaurant Business in the United States. “It was made in America and created by the creative Chinese immigrant restaurant owners.”

Chop suey was all the rage in the first half of the 20th Century. Today in a Chinese restaurant it’s usually found at the bottom of the menu, if it is listed at all. Photo by Juno1412/Pixabay

TO CHINATOWN FOR DINNER—AND CHEAP THRILLS

Lem Sen’s claims shocked the uptown sophisticates who since the 1890s had thrilled at “going down to Chinatown” and dining at one of their favorite chop sueys, as Chinese restaurants came to be known. Authentic or not, chop suey and the many other dishes on the menu were exquisitely prepared and delightful on the tongue. But there was something more. The ornately decorated restaurants themselves, the Chinese-populated neighborhoods, the curious shops selling who-knows-what, the odd decorations in the windows, the street banners with the chicken-scrawl lettering—the scene was simply too exotic for words.

“When the Chinese were driven out of rural areas and small towns in the West [in the 19th century], many of them went to live in Chinatowns in major cities,” says Yong Chen, professor of history at UC Irvine and author of Chop Suey, USA: The Story of Chinese Food in America. “At the same, they also emerged as tourist attractions.”

The allure was impossible to avoid. Somewhere in Chinatown (New York, San Francisco, Seattle, Honolulu, Los Angeles, it didn’t matter where), one could find the perfect little Chinese eatery—snug, private, hidden away. The interior decoration would be a riot of red flocked wallpaper, red paper lanterns, and red carpeting, with elaborately carved wooden chairs and, strangest of all, chopsticks. The service would be formal and efficient, though never obsequious. And the food would be fit for a king. Or an emperor.

Over the course of a century, the Chinese immigrants who created, adapted, and fused what is now a staple cuisine of the American diet found themselves traveling on a road of acculturation as long and winding as a well-boiled cellophane noodle.

AMERICA, MEET CHINESE COOKING

“There are perhaps 40,000 to 50,000 Chinese restaurants in America,” says Yong Chen. “They’re part of Americana. The U.S. is a country without a ‘national cuisine,’ and it is hard to find another cuisine that is more American than Chinese American food.”

Chen, who was born in China, admits that much of Chinese-inspired American cuisine developed separately from that of his homeland. When he arrived in America and ate in Chinese restaurants, the meals were unfamiliar.

“It was like, this is so different from the food we had in China,” he recalls.

Chinese arrived in America in great numbers following the 1848 discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in Northern California. Many of them went in search of the yellow ore on their own. Others labored as indentured servants in the mines with the railroads. Many more followed the Gold Rush-era slogan that the men who made money in the goldfields weren’t the miners, but the men who sold shovels to the miners.

Or who sold them chop suey.

Many “Celestials” (as Americans took to calling the Chinese immigrants because of an old term for China, the Celestial Empire) became cooks for the mining camps and railroad gangs. And many more opened restaurants, called “chow chow houses,” in West Coast cities.

But the rapid growth of Chinese immigration quickly produced a backlash. In 1851, 2,716 Chinese came to California, a place they called gam saan or “gold mountain”. The next year, following a devastating crop failure in their native land, more than 20,000 Chinese immigrants arrived. By 1862, pressure had grown on President Abraham Lincoln to sign an “anti-coolie” bill designed to stop or minimize the transportation of Chinese laborers by American vessels. Later, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 banned Chinese immigration outright and prevented immigrants who were already in the country from becoming naturalized citizens.

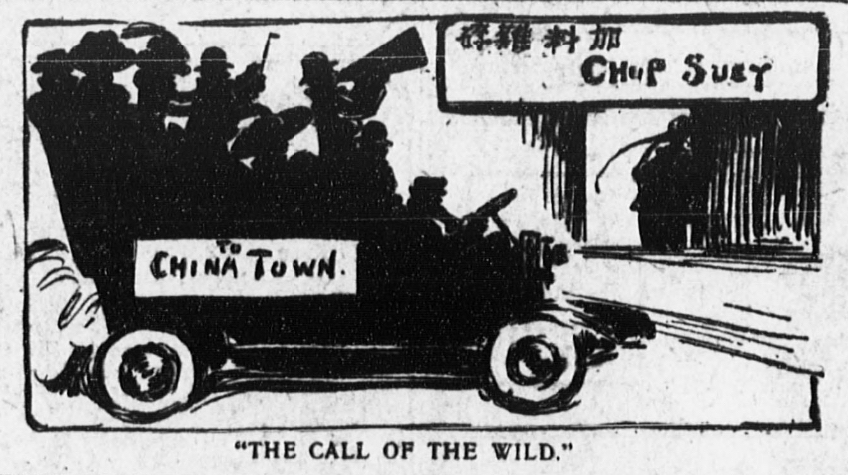

Newspaper cartoon depicting college kids on a spree in “dangerous” Chinatown, circa 1908.

RACISM, RUMORS, AND RESTAURANTS

The anti-Chinese sentiment took hold like wildfire on the prairie. Rumors spread that Chinese restaurants chopped up dogs and cats in place of beef and chicken. Ragamuffins in the alleys and lanes sang racially insulting songs about Chinese food.

That bigotry was strongest in the West, where thousands of “Celestials” worked in the mines, on the railroads, and in the restaurants, laundries, and other services in the fast-growing cities. But jobs in the mines and on the rails soon gave out. Unemployment reached more than 8% by 1878 and was even higher among miners and railroad workers.

The industrious Chinese were an easy target for the wrath of the unemployed whites, who thought immigrants were stealing their jobs. So, a growing number began to migrate eastward—to Chicago, Boston, Washington, New York, Philadelphia, and other cities where, they hoped, economic prospects would be better.

Yet even in the East, the Chinese were still set apart from the American mainstream because of their culture, language, traditions, and food. They tended to congregate in small, tightly packed neighborhoods within larger cities; organized their own social structures; created retail businesses that primarily served their fellow Chinese. Those neighborhoods, like the famous one in San Francisco, were called Chinatowns.

SOME VICE WITH YOUR RICE?

Every society has its vices, going back to the beginning of mankind. But in any Chinatown, those dens of iniquity were cheek-by-jowl against legitimate, family-oriented businesses because of constrained space. A gambling parlor might be next to a place of worship. And in a popular restaurant, an odor of poppy smoke might waft through the open windows from the “opium resort” down the mews.

In San Francisco in 1885, 10% of the population was Chinese, far too much for the city fathers’ liking. As anti-Asian sentiment reached a fever pitch, the city commissioned a building-by-building map of the 15 blocks of Chinatown, with colors of varying hues highlighting known opium dens, white brothels, Chinese brothels, and gambling parlors here and there among the vegetable purveyors, private homes, fish mongers, butchers, civic organizations, and schools.

The idea was planted: Let’s go down to Chinatown, where evil and temptation lay just around every corner and good times might be had by all. The cuisine there was ridiculously linked to the neighborhood’s “forbidden pleasures,” as some Chinese restaurants were rumored to be places of assignation with prostitutes or where one could buy opium.

THE BOHEMIAN CONNECTION

Chow mein and chop suey were no longer simply a meal; they were a statement, at least by a portion of the white community, that to “eat Chinese” was daring, avant-garde, bohemian. That sentiment would be part of American culture for at least the next 50 years.

“For some, going to Chinatown … will remind them of their childhood experience of eating in a local Chinese restaurant,” says Zai Liang. “For tourists, it is often a guaranteed and satisfying experience of getting souvenirs and happy meals. Still for others, Chinatown is kind of mysterious.”

One of the earliest printed mentions of chop suey in America appeared in the Savannah Morning News on July 25, 1886. The article was about New York’s Chinatown: “A Dinner in Wong Sing Wah’s Restaurant.” After describing his trepidation about such an exotic setting and odd menu items, the writer praises the restaurant’s cleanliness and the food’s tastiness, especially “chow chop suey.”

“It is a toothsome stew,” he writes, “composed of bean sprouts, chicken gizzards and liver, calve’s tripe, chagon fish, dried and imported from China, pork, chicken, and various other ingredients I was unable to make out.”

But the newspaper article then takes a darker turn as the reporter and his friend leave the restaurant and observe the goings-on in the surrounding laneways.

“They are inveterate gamblers and opium is everywhere,” the article states. “Almost every Chinaman has his own ‘lay out,’ and the smell of the burning drug is in every house.”

A German restaurateur in New York in 1908 thought he could do one better than the Chinese chop sueys by having an orchestra play Beethoven. Most importantly, he would open his Chinese restaurant uptown, not down in Chinatown.

“Down there,” he told the New York Sun that November, “is a certain mysterious atmosphere. People have heard queer stories and the place reeks with opium, and it looks queer and all that….”

The Sun went further, printing an illustration of a young businessman at a Chinese restaurant with a young woman nearly sitting in his lap and smiling coquettishly. “Busy at the office,” said the caption.

Hollywood, too, played a part in fostering those impressions. In the 1917 silent comedy The Detectress, the female star goes to Chinatown in search of stolen research describing how to make eyeglasses that allow the wearer to decipher the ingredients of chop suey. In her search of the neighborhood, she gets high from smelling someone else’s opium smoke and barely escapes the clutches of Chinese white slavers.

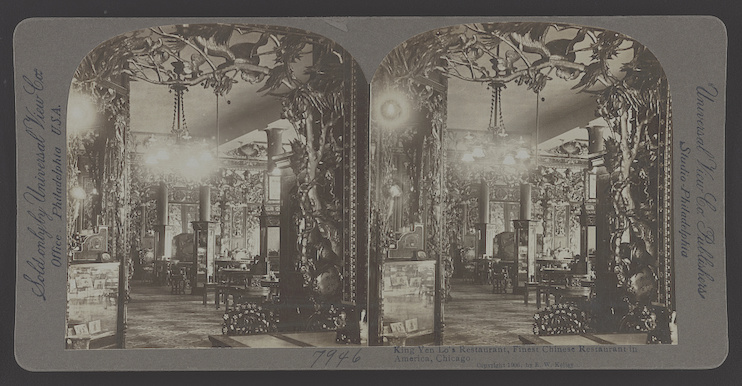

King Yen Lo’s restaurant in Chicago claimed to be the best Chinese restaurant in America. A description of the cuisine no longer exists, but the fact that an image of its interior was preserved on a stereoscope attests to its fame. Stereoscopes allowed left-eye and right-eye photos of the same scene to merge into a single three-dimensional image. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

CHINESE RESTAURANTS BECOME AN AMERICAN STAPLE

But Americans have always been ready to overlook a little immorality in quest of a bargain. Chinese restaurants were inexpensive; they appealed to all strata of society. No matter their religion or national background, people in the cities patronized the affordable restaurants and grew passionate about the wide range of tasty dishes. Especially in the dark and crowded tenements of the 19th and early 20th centuries, immigrants often had no adequate cooking facilities in their homes, so they flocked to the cheap and filling Chinese chop sueys.

“Unlike other foods, such as French food, Chinese food can be catered to people across all social classes,” says Liang, “the rich and not so rich. Chinese immigrant entrepreneurs are creative enough to modify Chinese food to the taste of Americans.”

The proximity of the immigrant Jews and Chinese on Manhattan’s Lower East Side ultimately led to a tradition that is still popular today in New York: Many Jewish families go out for Chinese food (often followed by a movie) on Christmas Day, because 125 years ago, Chinese restaurants were among the few eateries open on the Christian holiday. Even in 2023, as a result, quite a few Chinese restaurant owners will say that Christmas is their busiest day of the year.

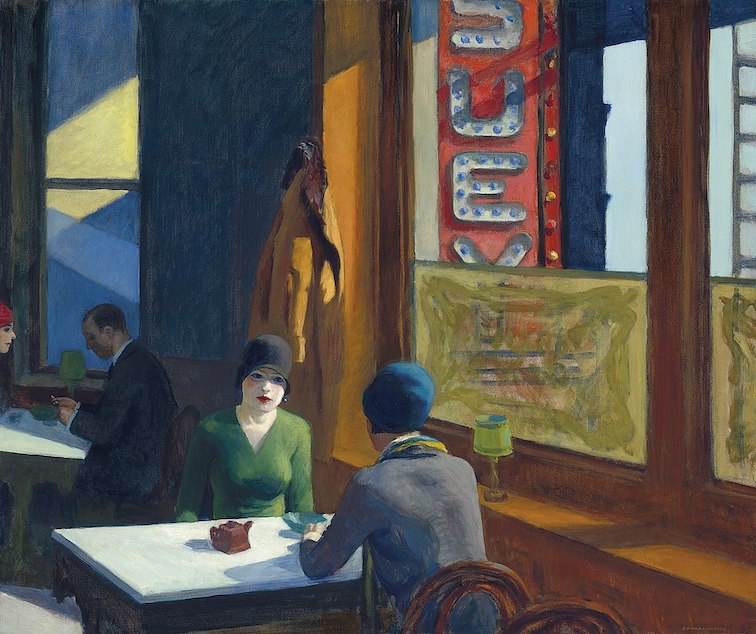

In 1929, American artist Edward Hopper painted “Chop Suey,” a portrait of diners inside a posh Chinese restaurant.

During all this time, up through the Depression of the 1930s, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 continued to bar Chinese immigration and naturalization. But after Japan’s invasion of China in 1930, and their ruthless behavior in cities like Nanking, Congress repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943. Americans began to view the Chinese not as yellow devils but as victims and partners in the war against totalitarianism.

Shortly after WWII, and with the end of the Exclusion Act, Chinese restaurants rapidly spread east from California and west from New York, until even the smallest Midwestern town’s Main Street or roadside strip mall had its own Lucky Buddha Garden, Double Dragon, or New Good Taste, usually featuring fried rice, lo mein, and other Cantonese dishes—and of course, chop suey. By 1959, New York City had more than 750 Chinese restaurants. Chinese recipes appeared routinely in the “women’s pages” of local newspapers.

“Chinese food grew in popularity in part because it is easily accessible, predictable (just like Burger King), and also affordable,” says Liang.

Very affordable indeed.

“Historically, its appeal came from convenience and especially low cost,” says author Chen. “These remain important characteristics of most Chinese restaurants.”

By the 1960s, smart homemakers could “serve six for less than $1.00” if they were smart enough to buy the family-size cans of Chun King chow mein or chop suey. Chung King, started by Italian American Luigino “Jeno” Paulucchi, soon grew into the largest producer of tinned Chinese food in the country. Chun King successfully advertised its ethnic food on commercial TV and made Chinese meals such a common part of daily American life that a family didn’t even have to leave home for an exotic dinner in old Cathay.

AN EXPLOSION OF REGIONAL STYLES

The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act opened America’s borders to skilled workers from around the world and family members of those who already lived in the U.S. As a result, the Chinese American population nearly doubled in the next 10 years. The new Chinese arrivals weren’t limited to those from Guangzhou, the source of the original 19th-century wave of Chinese immigration, but from Hong Kong, Taiwan, Sichuan, Hunan, Shanghai, and elsewhere, bringing with them their respective styles of cooking.

As they arrived, they frequently failed to meld into the long-established, tightly knit, largely Cantonese-speaking Chinatowns. The rents and the cost of living in the big cities were too high, so they found their way elsewhere: the suburbs. In the past 40 years, new and unexpected Chinatowns have flourished in such places as Monterey Park, California; Flushing, Queens; Orlando, Florida; Mesa, Arizona; and Plano, Texas.

The increased awareness and availability of Chinese cookery’s broad scope was heightened by the 1972 visit of President Richard M. Nixon to China, every moment of which was captured by the news cameras. The highlight was a banquet hosted by Prime Minister Chou En-Lai in Nixon’s honor. In New York’s Chinese American community, this was huge news. Michael Tong was the owner of Manhattan’s Shun Lee Palace, the first Chinese restaurant to earn a 4-star review in the New York Times. Tong managed to get an advance copy of the Nixon menu, telegraphed from Beijing. He immediately telephoned two high-profile local ABC news anchors, Bill Beutel and Roger Grimsby, and offered to prepare and serve the same menu items that very night. Did they want to film it?

Thanks to the ensuing publicity, Tong’s resulting dishes were a smash, including fish fillets in pickle wine sauce, duck liver spring rolls, and black mushrooms with mustard greens. People lined up at his door for months to pay $25 per person (approximately $180 in 2023 value) to sample the meal.

“It was huge news then,” Tong told the Times many years later. “The Chinese restaurant scene here exploded because of the Nixon trip.”

The famous Shanghai banquet at which President Richard Nixon ate Chinese food with Premier Chou En-Lai was not just a political event, but a huge publicity boon to Chinese restaurants in America.

THE RISE OF ASIAN FUSION

The expert chefs seemed to pour into America from the farthest reaches of China, bringing with them new tastes and traditions, ushering in a revolution in Chinese restaurants. Fewer and fewer diners ordered moo goo gai pan, egg drop soup, sweet and sour pork, or other traditional Cantonese dishes. Oh, they were still popular. But the new restaurants found an appreciative audience for the hot and spicy dishes of Sichuan (double-cooked pork belly) and Fujian (“Buddha Jumps Over the Wall,” with shark fins, sea slugs, pigeon eggs, and two dozen more ingredients). By the 1980s, a new cuisine called Asian Fusion was gaining popularity.

While much of the Fusion trend is unconnected to Chinese food (Korean-Mexican in Los Angeles, Viet-Cajun in New Orleans, etc.), it well may have been started by Chinese-American chefs, many of whom arrived in the U.S. via South America, Central America, and Cuba. In the 1970s and ’80s, New York was rife with Chinese-Cuban restaurants blending Asian and Hispanic cuisines.

No longer an enclave, New York’s Chinatown is a vibrant, bustling area that shows America’s embrace of Chinese culture, as well as its food. Photo by Wil540art/Wikimedia Commons

OLD-SCHOOL CHINESE STILL APPEALS

But for many of us a Chinese meal isn’t a spectacular, money-dropping spree into the rarefied world of celebrity chefs and cutting-edge culinary techniques. For most of us, it’s more like lunch at On’s in Pleasantville, New York.

On’s has been a fixture on Bedford Road for decades (“more than 30 years,” says the owner with some hesitation, not quite sure himself), an eight-seat, old-school, undecorated, harshly lit, counter-service eatery that relies more on take-out orders than on in-house diners. The menu items wouldn’t surprise a 1950s Denver housewife or a Mad Men-era go-getter in 1960s Manhattan: sweet and sour chicken, shrimp with lobster sauce, hot and sour soup, pork fried rice, and the like. The presentation is, admittedly, lackluster. The prices? Well, two people can order rice, soup, and a main dish for $17. For two people. At that price, who cares about the presentation? And the taste is out-of-this-world delicious.

But don’t expect a “traditional” fortune cookie with your bill.

After all, they were created by the Japanese. In America.

East-West News Service contributor Mark Orwoll is an old-school fan of sesame chicken, egg drop soup, and plain white rice, with duck sauce, please. The author of John Wayne Speaks, Orwoll recently wrote about the Hudson Valley and 5 Places Where International Travelers Can Find the Soul of America.