Narrated carriage tours through the most historic parts of Charleston are a staple of the city’s tourism. Guides are carefully vetted and tested. This carriage is passing Rainbow Row, a multi-colored stretch of elegant old buildings. Photo by Joe Benton

By Tom Adkinson

As I navigated the International African American Museum’s intellectually challenging artifacts and displays, a scene that lasted only a few moments captivated me.

A Black man, perhaps in his 60s, stood at a floor-to-ceiling window and gazed out on Charleston Harbor.

He was watching a hulking cargo ship approach, carrying who knows what kinds of goods. I couldn’t help wondering whether he was time-traveling to an era when ships sailing to Charleston Harbor carried human cargo.

The man stood in a place of extraordinary historic importance – Gadsden’s Wharf – the spot where historians say 40% of all enslaved Africans entered the colonies that a century later would become the United States.

The International African American Museum (IAAM) opened in June 2023 and today enhances Charleston’s already outsized visitor appeal.

The city – perennially on lists of America’s favorite destinations – is steeped in colonial and antebellum history, with attractions such as Drayton Hall (1738), the Nathaniel Russell House (1808) and the Charleston Museum (America’s first museum). Springtime is glorious with destination gardens such as Middleton Place. The restaurant scene is astounding given the city’s modest population of 150,000.

Plenty To Do and See

Throughout the year, Visitors pour in to stroll streets lined with pastel-colored homes. They often visit the top-notch South Carolina Aquarium and explore the U.S.S. Yorktown aircraft carrier before taking a horse-drawn carriage ride along streets lined with homes built by patrician plantation owners. The annual Spoleto Festival USA started in 1977 as a counterpart to Spoleto, Italy’s Festival del Due Mondi. It sponsors 100 performances in nine venues, one of them being the Dock Street Theatre, which occupies the site of the first building in the 13 colonies designed for theatrical use.

The idea for the International African American Museum burst into this crowded scene in 2000 when former Mayor Joseph P. Riley Jr. pointed out how Charleston was ignoring part of its own story. While slavery is a major focus of the IAAM, it is not a slavery museum. Its scope is the massively larger story of African American culture and history overlaid on the global African diaspora.

It opened amid Charleston’s reassessment of its slave history, its continuing fealty to the plantation culture of the antebellum South and the emotional scars left by the 2015 assassination of nine Black worshipers at the Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Receiving Human Cargo for 137 years

The first Africans arrived in Charleston in 1670. The volume ebbed and flowed, but for the next 137 years, approximately 150,000 enslaved men, women and children plodded across the land where the IAAM stands

Actually, the IAAM isn’t directly on Gadsden’s Wharf. It hovers over it. The rectangular structure, with windows looking out to sea and inland toward downtown, stands 13 feet above the ground on 18 cylindrical columns. Tabby, the colonial construction material made of oyster shells, lime and sand, coats the columns.

When covered with water, images incised into the bottom of a tide pool on the harbor side of the museum appear to vibrate so that they resemble enslaved Africans packed into the hold of a ship crossing the Atlantic. Photo by Tom Adkinson

The Architect’s Newspaper described it this way: “It seems to step out of the Atlantic and pause between the past and the future.”

Matteo Milani, one of the museum’s architects, went so far as to note that “the site is more important than the building itself.”

A haunting work of art lies beneath and beside the end of the museum closest to the harbor. It is a shallow fountain reminiscent of a tidal pool. What is under the water transforms from abstract to realistic when you realize the patterns are full-size human figures. Those outlines recall the horrors of enslaved Africans packed into ships for transport across the Atlantic Ocean.

The transatlantic slave trade lasted 366 years, with 36,000 documented voyages that uprooted 12.5 million Africans. More than one-sixth of them, 1.8 million, did not survive the journey.

The Two Scariest Words

Tonya Matthews, IAAM’s president and CEO, has a Ph.D. in biomedical engineering. She’s also a poet, a former university administrator and a former science center executive.

“I was pleased that I wasn’t pigeonholed as someone who could run only science museums,” she says.

Her demeanor reveals that she has the heart of a teacher and the communication skills to initiate conversations, including ones about uncomfortable topics. “The two scariest words in English are ‘algebra’ and ‘racism.’ Parents freak out when they have to teach their children about these topics,” she smiles.

International African American Museum CEO Tonya Matthews sees Charleston’s newest museum as a place where people can discuss controversial topics. Photo by Tom Adkinson

Dr. Matthews sees her museum as a place for learning and a catalyst for understanding.

“The museum deals with tricky, sticky and challenging topics, but today’s society lives in a new era with the ability to discuss these topics. Ears are open,” she states, adding that the museum can be “a gentle, inspiring neighbor to spark conversations.”

Topics in the galleries are both gigantic and granular. You can be overwhelmed trying to absorb the enormity of the transatlantic slave trade and the global influence of African culture that stretches from London to Sao Paulo to Toronto. Conversely, you can focus on topics such as the Buffalo Soldiers, Pullman porters and the Mardi Gras Indians of New Orleans.

Visitors’ reactions span a wide spectrum. Some people are solitary and silent. Others implore family members to examine an artifact or read a display panel. Some older visitors tell younger companions their own stories to personalize the information at hand.

And, yes, sometimes strangers talk with strangers.

“When I see people talking with others . . . that’s the holy grail of museums,” Dr. Matthews said.

I myself exchanged pleasantries with Sam and Dorine O’Neal, who were visiting with a church group from Spartanburg, S.C. Their matching shirts bore the southern saying of “Bless your heart.” We all commented on the museum’s scale and impressiveness, and then Sam turned pensive.

“This is a reality check. Some of this, I can’t look at for long. It brings tears to your heart,” he said.

Center for Family Research

One of IAAM’s most important spaces belongs to the Center for Family Research. It helps individuals connect to their family histories and ancestors.

Because of slavery, Blacks in America often cannot document very many generations back, but resources do exist, and the center maintains digital archives of marriage records, family Bibles, obituaries, the records of free people of color and pension files of men who served in the U.S. Colored Troops and other data.

An IAAM ticket includes admission to a 30-minute “Getting Started with Genealogy” program (Tuesday through Friday). For a fee, you can book a virtual one-on-one consultation with a staff researcher.

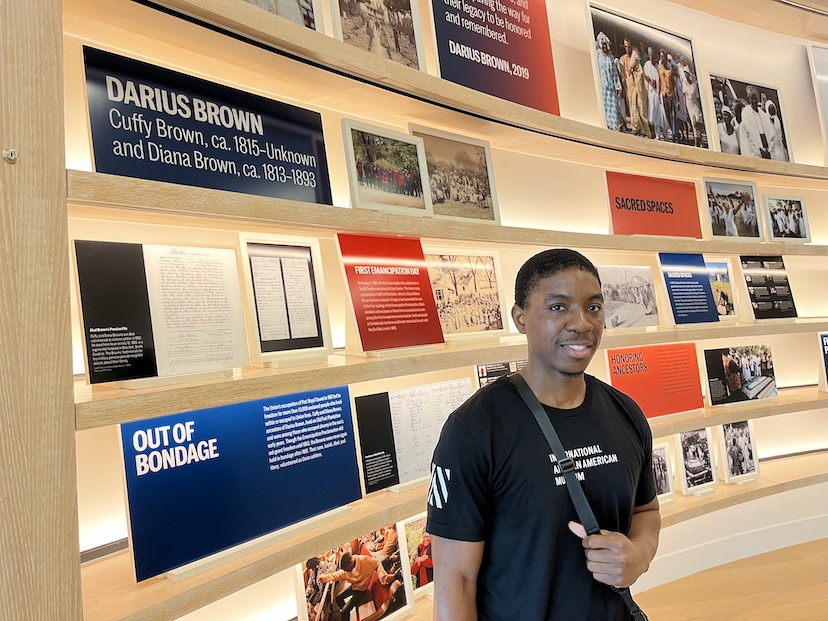

The gallery at the Center for Family Research is an open, airy space filled with multi-generational stories of well-known people (Michelle Obama, for instance), and intriguing tales of lesser-knowns, such as Darius Brown.

Photos and plaques about Brown certainly intrigued me. He is a young South Carolinian who turned to the center for research help, and the center uncovered an amazing story.

It traced Brown’s family to 1861, when Union troops occupied Port Royal Sound south of Charleston, freeing 10,000 enslaved people who lived within or escaped to Union lines. Among them were Cuffy and Diana Brown and their children. Their sons – Isaiah, Abel and Harry – enlisted into the U.S. Colored Troops, and Isaiah was Darius’s great-great-great grandfather.

One of the hosts greeting visitors to the center saw my interest in Darius Brown’s search and approached me to ask whether I had recognized anyone in the photos.

I studied a photo, looked at my host, grinned sheepishly and said, “Really?”

“Yep,” the host said. “I’m Darius.”

Darius Brown, a student at the College of Charleston, also works as a guide at the Center for Family Research. IAAM genealogists helped him discover his family’s past. Now he helps others trace their lost lineage. Photo by Tom Adkinson

Out in the City Today

Race and the relations between races have been part of Charleston’s story since Africans first arrived in 1670.

They evolved through the colonial and plantation eras, through the multi-generational development of the Gullah Geechee culture (the isolated Black way of life in the Carolina Lowcountry and part of Georgia and Florida), through the first shots of the Civil War on Fort Sumter, through the 2015 massacre at Mother Emanuel AME Church and through the opening of the IAMM.

“Whether white Charlestonians admit it or not, they are captivated by the Gullah culture. It is integrated into our culture. We (meaning white Charlestonians) cannot escape being influenced by Black culture,” said Joe Benton, a Charleston native, who in retirement sells artistic Charleston and Lowcountry photographs at the Charleston Night Market.

Benton explained that he was talking about Gullah’s influence on food, music, crafts such as sweetgrass baskets, hospitality and even language – and how that culture is part of Charleston’s broad appeal as a destination.

“With enough shrimp and beer, I can get back speaking some Gullah,” he said with a hearty laugh and recollections of easy childhood interactions with Black peers.

Woven by hand in Gullah communities in the Lowcountry along the Atlantic Coast, sweetgrass baskets are sold in outdoor markets in downtown Charleston. Photo by Joe Benton

All was not sweetness and light, however. Benton recalled staunch white opposition to a Black hospital workers’ strike in 1969 during the Civil Rights movement. White Catholic priests marched with strikers, and Benton remembers one young priest who ripped off his clerical collar and confronted a parishioner who had cursed the priests’ support of the strikers.

A memory on the flip side of that story was the first theatrical production performed for an integrated audience in Charleston. That was a 1970 performance of “Porgy and Bess” at the Gaillard Auditorium.

“That, to me, was an important point of recognition of a change in tenor in the city,” Benton said.

Nigel Drayton, the Black owner of two Nigel’s Good Food restaurants and a separate barbecue joint, says he’s too busy making Geechie Wings and Lowcountry Ravioli (chicken, bacon, collard greens, roasted corn and cheese) to think much about race. He’s in the hospitality business that serves and employs everyone.

“The first place I worked (he started busing tables at age 15) was integrated. Work relationships led to after-work connections. I’ve been blessed with color blindness in my field,” Drayton said.

Beyond race, Drayton and others cite a demographic, economic and cultural change in Charleston – gentrification that comes with population growth, especially with the addition of people from other regions of the country.

“There used to be a lot more mom-and-pop shops of all types downtown. In the last 20 years, that has diminished. The big wigs and the big money came in,” Drayton observed.

Tia Clark takes parents with children out to catch crabs. Having grown up in Charleston, she counts herself as a “ben-yah.” Photo by Tom Adkinson

Tia Clark, owner of an outdoor adventure business called Casual Crabbing with Tia and someone who grew up on Charleston’s King Street, said the same thing and used a Gullah term to separate people.

“You’re either a ben-yah or a come-yah,” she said, meaning you have deep roots here or you’ve only recently arrived.

The volume of “come-yahs” worries many Charlestonians, both Black and white.

At Mother Emanuel AME Church

Rev. Eric Manning assumed the pulpit at Mother Emanuel AME Church soon after a 21-year-old white man murdered nine people attending a Bible study at the church in 2015. The murderer said he wanted to start a race war. That didn’t happen. But his actions did bring attention to the starkness of race relations.

In an interview, Rev. Manning diplomatically said he still is assessing the racial world in what long-time Charlestonians call the Holy City. He contemplated the question in an office filled with books, photos and an architect’s model of a memorial to the Emanuel Nine.

Child looking at a historic portrait of a black family hanging inside Charleston’s International African American Museum. Photo courtesy of Explore Charleston

“The racial situation is evolving,” he says, noting the enthusiastic curiosity that has greeted the new African American Museum.

“I’ll be interested in the demographics of the visitors,” he says, wondering whether Blacks will embrace the powerful story there and if whites will see it simply as a visitor attraction to check off a list.

Back at the IAAM, Malika Pryor, the chief learning and engagement officer, offers an optimistic thought on that point. “As an encyclopedic museum, we hope to encourage and inspire people of every background. We welcome all. For anyone who wants to learn, we are here.”![]()

Born in Columbia, SC, Tom Adkinson now lives in Nashville, TN, but maintains his affinity for South Carolina and its many stories. His previous writing for EWNS focused on the growing popularity of dark sky star parties.