Built in 1936 to mark the quadricentennial of the city’s founding, The Obelisk is located at the intersection at 9th of July and Corrientes Avenue in the Plaza de la Republica in central Buenos Aires.

By Nancy Wigston

Imagine a chunk of 19th-century Europe breaking off and floating to South America where it lands at the mouth of the Rio de la Plata, the widest river in the world. Though anchored to a continent filled with Amerindians and the mestizo descendants of Spanish and Portuguese conquistadores, people in this settlement of Buenos Aires look Italian, French and German. Even stranger, these South Americans, who call themselves Porteños, admire Britain, with whom they share a love of polo, soccer and the glories of succulent, marbled beef. As the old saying goes, “An Argentine is an Italian who speaks Spanish, thinks he’s French, but would like to be English.”

With an exchange rate that favors visitors from more stable economies (1 USD=81.5 AR Pesos), Buenos Aires seduces tourists with its sophisticated lifestyle, green space, architecture, excellent steaks and Malbec wine.

And the tango. This melancholic, sensual phenomenon, a strutting ritual of seduction, was born in port brothels in the 1870s. It soon moved from the louche world of gauchos and bar girls to the world of European immigrants arriving a decade or two later. In Buenos Aires, tango soon became an important link to the new land.

Born in Buenos Aires, the passion for tango is firmly rooted in cities like Paris, Tokyo and Shanghai. The dance requires coordination and touching.

Inseparable from Buenos Aires’ identity, tango today draws tens of thousands of visitors from all over the world who come to dance. Many of these tangueros head directly to Maria’s Tango House, an antique mansion from 1890 with large bedrooms with hardwood floors and high ceilings. The hotel has a spacious ballroom where private dance instructors will prepare you for milongas, tango nights on the town that follow a strict etiquette. A woman awaits a man’s invitation to dance. With a slight nod, or cabeceo, she accepts.

From chic tango dinner shows to pass-the-hat street tango performances, this dance is everywhere. Supper clubs send transport to your hotel. One of the best tango clubs is located in the working class barrio of Boedo at Esquino Homero Manzi. Named for the famous tango lyricist, this symbol of urban culture offers an evening of dance history with dazzling costumes, exceptional musicians and gymnastic dancers who move between tables to the rhythm of songs from 1870 to present. All this with an excellent three-course meal costs about $50 for two.

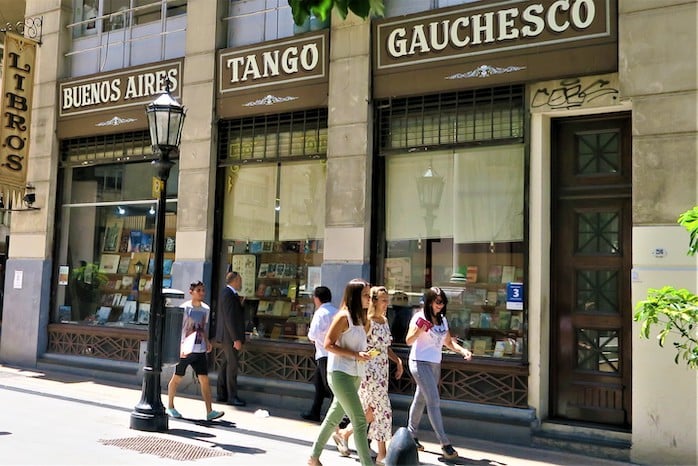

There are dozens of tango clubs in Buenos Aires. Bookstores are equally beloved. These young women are walking past Liberia de Avila, the city’s oldest bookstore which was built in 1785.

After a few days in Buenos Aires tango takes up residence in your head. While touring the Oncé district – the city’s Lower East Side – I purchased a souvenir CD of old tango hits. It made perfect sense at the time. As did my decision–buoyed by strangers’ compliments after I danced at Museo del Tango, a nightspot in the Central Business District of Microcentro, to book a private lesson the next morning.

The young teacher arrived (wife and baby in tow), and we proceeded to straighten our spines, raise our arms, not look at each other, then advance, retreat, twirl and attempt the kicking between the legs move intrinsic to tango. Alas, the morning light revealed all. I was hopeless. The experts kindly staged some professional-looking photos, arranging my right leg fetchingly around my teacher’s waist as I smiled confidently.

One of the city’s most skilled troupes performs–without dinner or drink options–several times a week (about $20 per ticket) in the Borges Cultural Center theater, in the centrally located Gallerias Pacifico (corner of Florida and Cordoba), a lavish mall constructed in 1896 as an art gallery. The top floors honor hometown short story writer, poet–and guide to magical worlds–Jorge Luis Borges. Opining on the tango, Borges wrote that “at the beginning, it was an orgiastic mischief, today it is a way of walking.”

There are many ways of experiencing this cosmopolitan capital of just under three million. Nothing, not even tango, is compulsory. Explore its many barrios on foot, by taxi, or by taking the efficient subway system. English attendants are rare in the subway so ask your hotel how to purchase a multi-stop pass on routes where passengers often sip from thermoses of the herbal tea called maté as they commute to and from work.

Time for siesta in the Plaza de Mayo with Casa Rosada in the background. Built in 1811, the May Pyramid in white celebrates Argentina’s independence from Spain.

Where to start? Easy. Go to Plaza de Mayo, the beating heart of the original Spanish colony, Monserrat, laid out in the grid pattern admired by Charles Darwin during his 1833 visit. The Plaza’s Casa Rosada (pink house), the official executive mansion and office of the President of Argentina, should look familiar. Millions of Evita fans have seen its balcony where, on October 17, 1951 President Juan Peron held his ailing wife Eva (Evita) as she valiantly waved to the cheering masses. American singer Madonna recreated the moment on screen in 1996, singing the Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice anthem, “Don’t Cry for Me, Argentina.”

Independent from Spain since 1816, Argentina experienced massive economic growth in the late 19th century. Exports of beef and grain to Britain and Europe grew the economy exponentially, attracting an influx of European immigrants. Yet Buenos Aires has always had a somewhat racy reputation with its northern neighbors. Witness Gilda, the 1946 film that introduced the world to fiery red-haired Rita Hayworth who plays a Buenos Aires casino singer:.

More than once, government mismanagement has threatened the country’s stability. A truly spectacular default in the early 21st century on loans from the World Bank left huge debts and instability. Debt repayments have helped, but a history of dictatorships and military interventions have not, so Buenos Aires remains an enchanting bargain for tourists.

Over coffee and sweets at the elegant old Café Tortoni on Av. de Mayo, at the corner of Suipacha Street, there’s time to reflect on Buenos Aries’ strange, enduring combination of beauty, intellect, and tumult, while gazing at the wax figure of Jorge Luis Borges, seated with literary friends at his favorite table.

Juan Peron is not depicted in the café but can claim to have founded modern Argentine socialism. He was overthrown in 1955, later regained the presidency and was followed by his third wife, Isabel, who also was deposed. Today Peron’s brand of populism and the fame of his second wife endure.

Evita fans can visit the Eva Duarte Peron Museum –a short taxi ride from Café Tortoni in the Barrio Palermo—to be dazzled by her humanitarian work for women and the poor—and by her smashing wardrobe. Santa Evita’s flower-bedecked mausoleum draws a stream of admirers across town to Recoleta Cemetery–the most expensive real estate in town. Fourteen acres of winged angels, poignant statuary, and memorable family tombs make this seem less like a cemetery and more like a gated subdivision.

The grave of Evita Peron in Recoleta Cemetery attracts thousands of people. Few know the details of Juan Peron’s populism or the scope of Evita’s work on behalf of the poor. But most can sing the refrain to “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina.”

Evita’s death at thirty-three from cancer plays on as the nation’s favorite melodrama. A kind of counter-Evita, culture maven Victoria Ocampo -also laid to rest in Recoleta Cemetery – presided over a writers’ salon for much of the 20th century and entertained international luminaries in her family’s summer house in San Isidro, 13 miles from Buenos Aires.

Famed for the cats’ eye-shaped white framed glasses she wore into old age, Ocampo’s tasteful rooms sparkle with photographs of friends like Albert Camus, Igor Stravinsky, Graham Greene, and Indira Gandhi. On her death in 1979, she willed the property to UNESCO. Sunday lunch at Villa Ocampo is an elegant affair, highly recommended.

Perhaps Buenos Aires’ greatest attribute is its ability from one decade to the next to seduce new generations of travelers with its luxurious affordability. On my first trip, I stayed in a renovated belle époque B&B, in Microcentro, once owned by Che Guevara’s aunt. I headed down to Florida, the pedestrian-only shopping street, then turned up toward 9th of July, the world’s widest avenue, to discover the sumptuous 1908 Teatro Colon, a 2500-seat opera house with free daily tours.

Every immigrant group has left their mark on Buenos Aires. La Boca is a working-class barrio near the port settled by Italians who turned shipping containers into living quarters. It is popular for its pedestrian walkway bursting with art galleries, buildings painted in primary colors and street tango. La Boca’s premier league soccer team, the Boca Juniors, are stars in this futbol mad country. Diego Maradona, the best footballer of his generation, began his career with the Boca Juniors. Tourists are cautioned to be alert in La Boca and several other popular barrios, especially at night.

San Telmo, six blocks south of the Plaza de Mayo, exudes a faded charm reminiscent of its heyday as the wealthiest city barrio. Antique shops, a Russian Orthodox Church, tango clubs, a Sunday flea market, and funky cafes line the old cobblestone streets. Booklovers will enjoy browsing The Walrus, the city’s excellent English-language bookstore.

Since its 19th century glory days, public art galleries and lovingly landscaped gardens have defined Buenos Aires style. Plaza San Martin at the northern end of pedestrian-only Florida St in Retiro occupies the former headquarters of Argentine liberator Jose de San Martin. It serves as a tribute to both San Martin and the talented French urbanist Charles Thays, another immigrant who fell in love with this country.

Two more Thays’ designs are in Palermo, the largest of the city’s barrios. Palermo’s 1892 Botanical Gardens on Av. Santa Fe covers over seventeen acres and reflects Thays’ love of flowering jacaranda, orange coral trees and ornate glasshouses.

Bosques de Palermo (Palermo Woods) celebrates the 1852 overthrow of dictator Juan de Rosas. First opened in 1875 on 988 acres of Rosas’ former estate, today’s park features an immense rose garden, artificial lakes, sculptures, white bridges, and a poet’s corner. A morning wandering the gardens nicely concludes with lunch at Casa Cavia, a courtyard oasis that attracts the city’s upper crust in Palermo Chico.

In nearby Recoleta on Avenida del Liberatador the Bellas Artes Museum is free to the public. It has an enormous collection of South American and European masterpieces, including Rembrandt, Van Gogh and Chagall. A pleasant walk takes you to back to Palermo and Buenos Aires’ Museum of Latin American Art. Street jugglers entertain outside the entrance on Avenida Pres. Figueroa Alcorta.

The latest additions to the cityscape are found in Puerto Maduro, where reclaimed dockside warehouses, five-star hotels and pricey restaurants combine to attract a moneyed hipster crowd. Puerto Maduro has its quirks. All the streets are named for women.

Intriguing, vibrant cities like Buenos Aires often provoke could-I-live-here fantasies. Recoleta, northwest of Retiro, with its upscale shops, restaurants, clubs and hotels, represents Buenos Aires at its most seductive. When Californian Brent Federighi arrived in Buenos Aires in 2004, he fell in love with a Belle Epoque mansion that he named The Poetry Building. He created seventeen luxury apartments, each furnished with a blend of modern and antique furniture, and original art.

On the top floor, guests enjoy the small pool area. Drinks and fresh popcorn are on hand, and an organic garden occupies the roof. On arrival, guests receive the essentials: excellent coffee, a bottle of Argentine Malbec and a box of pastries.

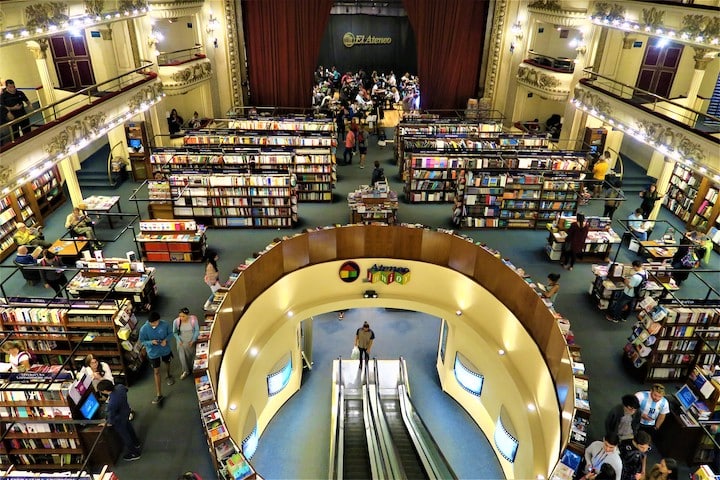

A few streets away, Rapanui serves the best ice creams (try the dulce de leche) in a city famous for sweets. On Avenida Santa Fe, the big attraction is Al Ateneo Grand Splendid, doyenne of the city’s seemingly infinite number of independent bookstores. This 1919 theatre-turned-cinema-turned bookshop has 100,000 titles and thousands of records and CDs, displayed on tiers where audiences once enjoyed a night out. The former stage is a café.

El Ateneo Grand Splendid is one of the city’s lavish book stores. Packed with more than 100,000 books arrayed from basement to balcony the store also boasts a small cafe on the theater’s old stage that’s always packed with customers.

With grandeur like this, why are Argentina’s finances so wobbly? Obviously, Covid hasn’t helped. But Federighi is philosophical. “Argentina simply spends more than it makes.” But the hotelier is sanguine: “After breaking, the country always seems to find its re-footing somehow, usually on the back of its natural resources. Coming out of the 2001 debacle it was the rising commodity prices that got us out of the hole. Not sure what it’ll be next time.”

Contrarians thrive in Buenos Aires. Take graffiti, for example. When economics or politics get heavy, artists express themselves on city walls. An outfit called Graffitimundo began street art tours that grew massively popular, culminating in a 2017 feature length documentary called “White Walls Say Nothing.” An international hit, the film is shown periodically in Buenos Aires and is available online.

Here Comes the Bride

An astonishing amount of art by fifty-odd artists graces both trendy and not-trendy barrios. Political messaging—ironic Mao faces, giant bulls mocking south American machismo, sci-fi aliens mimicking the military—mix outrage with satire. Giant side-by-side wall portraits of assassinated American President JFK and Argentine-born revolutionary Che Guevara once shared a wall in Palermo Soho.

As for writing on walls, that has been “illegal but tolerated” since the 1950s when politicians paid for supportive messages. But this century’s explosion of street art is something new, an activists’ dream made real.

Still, not every message is political. A corner house on the tour is painted “with permission” of its nonagenarian owner to resemble a flowing sonnet in yellows, pinks and purples.

After visits to barrios like Colegiales and Villa Crespo, a three-hour graffiti tour might end in avantgarde Palermo Soho, where “Hug Here” is stencilled on the pavement. Many couples oblige. Graffitimundo offers three-hour tours by minibus from your hotel and back.

For those who find themselves smitten by Buenos Aires, the city proves difficult to shake. In their South American city with a dash of European flavor, Porteňos stay up late, drink gallons of coffee, dance passionately, and consult psychologists who number around 30,000, the highest percentage per capita in the world.

For those who find themselves smitten by Buenos Aires, the city proves difficult to shake. In their South American city with a dash of European flavor, Porteňos stay up late, drink gallons of coffee, dance passionately, and consult psychologists who number around 30,000, the highest percentage per capita in the world.

Orange juice comes freshly squeezed. Bathrooms have bidets. Newspaper and flower kiosks dot the streets. Between five and seven, ladies and gentlemen of the old school meet friends for snacks and conversation. The younger crowd stays up into the wee hours. A good steak dinner costs roughly $30 in a city bursting with bookstore-haunters, art lovers, opera, rock, and jazz fans.

Lovers and rebels are integral to this place, they always have been. And all of them think they can dance the tango.![]()