By Thomas DeVoss

As an architect I often get asked, “What are your architectural styles?” I tend to deflect this question, saying I don’t really have a style, but that instead I have an approach to each project, and that varies with the location, climate, client needs, budget, etc.

On the third page of the introduction to Architectural Styles, author Margaret Fletcher either exposes or validates me: “Contemporary architecture is moving at a rapid pace and its architects are often not keen to be labeled. They work within a set of objectives that are important both to the academy of architecture and to their individual clients; their work tends to fall into multiple categories and can be cataloged a variety of ways.”

Yes, exactly. Thank you.

She goes on, “At any given time in history, the people, the culture, and the architects respond to the current situation. They act in the now, the present of that time….This book, by design, is a visual narrative that will take you on a drawn journey through history.” Interesting.

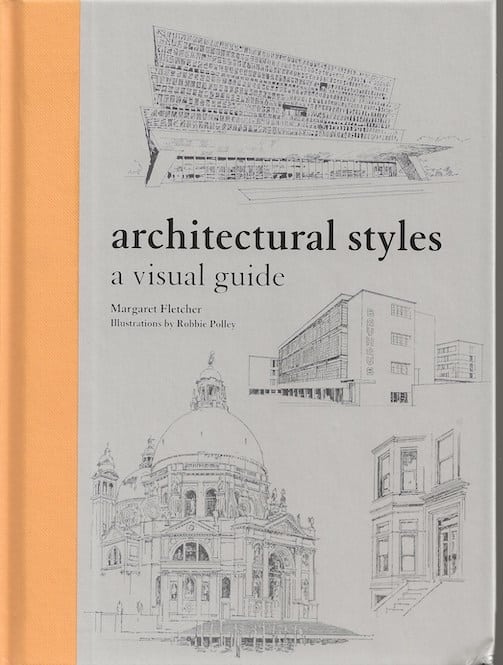

Published by Princeton University Press, Architectural Styles – A Visual Guide invites you to stand in the footprints of Julius Caesar, Cleopatra, or Shakespeare and envision how life used to be. Adopt this mindset and this book becomes the sketchbook of a time-traveling artist, sketching man’s greatest creations from antiquity to current day.

Architectural Styles – A Visual Guide is organized into five sections: Ancient and Classical, Medieval and Renaissance, Baroque to Art Nouveau, and Modern to Contemporary (each section has further subsections). The sketches are simple but clear throughout.

If the sketching style looks familiar to you, it might be because the illustrator, Robbie Polley, has created watercolor perspective drawings for quite a few DK Eyewitness travel guides: Rome, California, Venice, Vienna, among others. What we see in Architectural Styles is a pared down, pen-only version of his work. The illustrations are simple, but even with fewer pen strokes they are able to fully communicate the essence of the featured buildings. It’s instructive to see the same hand sketch buildings over the span of architectural history. It makes architecture and design feel like a constant evolution, tied together in its similarities, its elements.

Elements is the final chapter in this book and explores Domes, Columns, Towers, Arches, Doors, Windows, Roofs, Vaults, and Stairways, the combination of which creates the visual evolution of architectural history.

The layout of the entire book is clean, with pleasing fonts, beautiful sketches, and well balanced composition. I’m not surprised to see that Ms. Fletcher is also the author of another book called Visual Communication for Architects and Designers: Constructing the Persuasive Presentation, because the graphic design in this book is on-point.

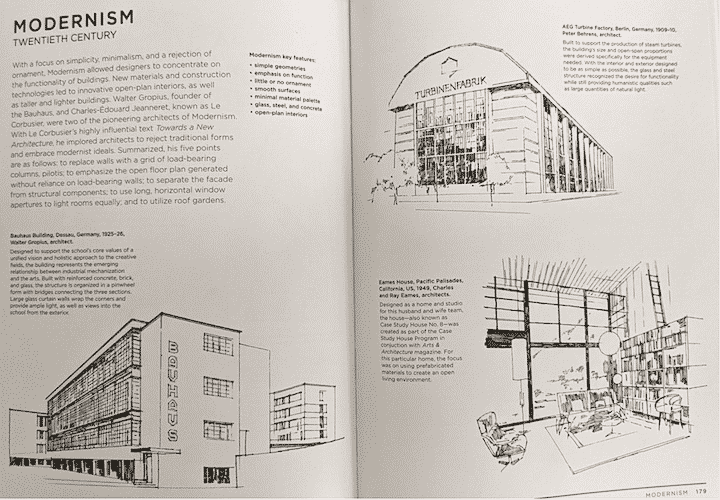

The part that is most interesting to practicing architects and world travelers interested in international design is how the author chooses to classify contemporary architecture. Starting from most recent and heading back in time, Ms. Fletcher chooses: Parametric, Biomorphic, Eco-Architecture, Deconstructivism, Postmodernism, High Tech, Metabolism, Brutalism, Constructivism and Modernism.

Parametric, Biomorphic, and Eco-Architecture are styles that are active, ongoing and evolving. See the facade of Diller Scofidio’s Broad Contemporary Art Museum (2015) in Los Angeles for an example of Parametricism. For Biomorphic architecture, visit any of the bridges or buildings of Santiago Calatrava; you will see wings on his Quadracci Pavilion at Milwaukee’s Art Museum (2001) or ribs in the soaring atrium of the World Trade Center Transit Hub in New York (2004). A prime example of Eco-Architecture would be Stefano Boeri’s Bosco Verticale (2014) in Milan, Italy; two residential skyscrapers with 18,000 plant specimens adorning their terraces.

The sketches of Modernist buildings look like structurs that are designed today, so clearly we’re still somewhat in that phase (Is my style Modernist? Hmm).

The author uses Le Corbusier’s Towards a New Architecture to summarize her version of Modernist philosophy: replace walls with a grid of load-bearing columns (pilotis), utilize open floor plan, separate facade from structural components, expansive use of windows to bring in natural light, and roof gardens. This is not exactly how I think about Modernism, but it’s not far off. To me Modernism is synonymous with simplicity and efficiency. It’s a minimalist philosophy that rejects unnecessary ornament and ostentatious displays, but focuses on blending with nature and celebrating raw materials (see Eames, Neutra, Van Der Rohe…). This book is in some ways is Modernist in its orientation.

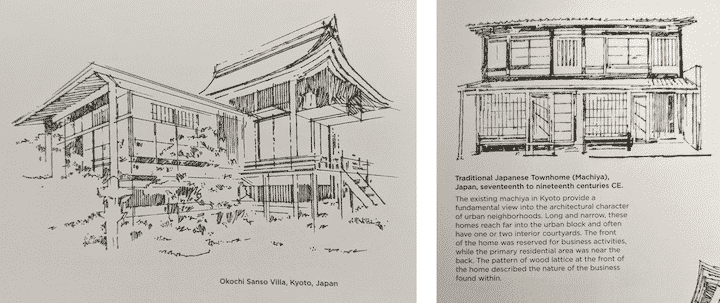

The Modernist window grids of the Bauhaus building and of the Eames house, recall buildings I’ve just seen earlier in this book, but which are from hundreds of years ago, such as the traditional Japanese Townhome from 17th-19th centuries or the Okochi Sanso Villa in Kyoto (which was technically built in the 1930s but uses traditional principles).

The Modernist window grids of the Bauhaus building and of the Eames house, recall buildings I’ve just seen earlier in this book, but which are from hundreds of years ago, such as the traditional Japanese Townhome from 17th-19th centuries or the Okochi Sanso Villa in Kyoto (which was technically built in the 1930s but uses traditional principles).

Traditional Japanese villa architecture is basically a wood-based modernism, with post and lintel construction allowing wall panels to slide and reveal panoramic views of nature. Ms. Fletcher includes an interesting fact about the Japanese Townhome (Machiya); that the wood lattices in front of the building would describe the nature of the business.

The machiya is Japan’s (and specifically Kyoto’s) live-work set up appearing as early as the Heian Period (8th -12th centuries), developing through the Edo period (17th-19th centuries) and continuing to today. Designed to house urban merchants and craftmen, some machiyas are still functioning as houses, businesses, ryokan, and vacation rentals.

Often found in Kyoto, traditional machiya architecture puts business activities in the front of the building and leaves residential for the back of the house.

The typical machiya is a long wooden home with narrow street frontage that stretches deep into the city block and often contains small courtyard gardens. Wikipedia tells me that: “the front of a machiya features wooden lattices, or kōshi (格子), the styles of which were once indicative of the type of shop the machiya held. Silk or thread shops, rice sellers, okiya (geisha houses), and liquor stores, among others, each had their own distinctive style of latticework. The types or styles of latticework are still today known by names using shop types, such as itoya-gōshi (糸屋格子) (lit., “thread shop lattice”) or komeya-gōshi (米屋格子) (lit., “rice shop lattice).[9]” Very interesting facades. The use of koshi panels is quite a nice way to bring continuity, complexity, order, and beauty to a street front.

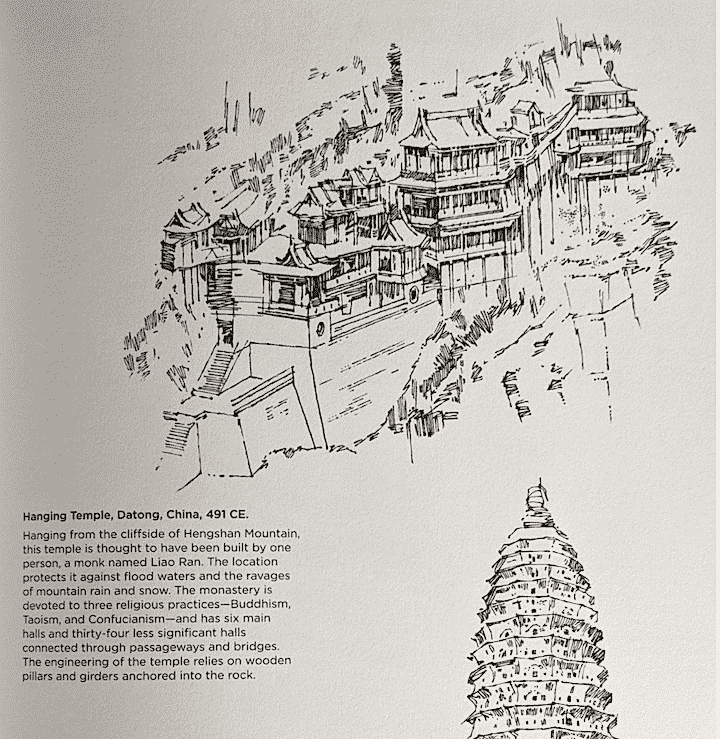

It’s tempting to flip through books like these without reading them because they have intricate images, but in this case, it’s worth your time to read the brief descriptions. The pithy commentary provides some interesting factoids about most of history’s great buildings. You’ll sound smart at that cocktail party when the Hanging Temple of Datong comes up and you can chime in with, “What I find most fascinating about the Hanging Temple (aside from the verticality of the Hengshan cliffs as site location, of course) is that it was said to be constructed by one monk. Imagine that, 9 main halls and 34 subsidiary halls all done by Liao Ran.” Or something equally erudite.

Or if the subject of arches comes up, you’ll be able to add: “I’m sure you all know this, but the largest unreinforced brick arch in the world still stands, at Taq Kasra in Iraq. It’s the Arch of Ctesiphon (27m across), built by the Persians in the 3rd century CE…” (Ctesiphon is pronounced without the “C”, by the way).

Or if the subject of arches comes up, you’ll be able to add: “I’m sure you all know this, but the largest unreinforced brick arch in the world still stands, at Taq Kasra in Iraq. It’s the Arch of Ctesiphon (27m across), built by the Persians in the 3rd century CE…” (Ctesiphon is pronounced without the “C”, by the way).

If someone asks when people started using glass for windows, you’ll be able to answer, “Well, glass has been used as vessels, weapons, and in art going back millenia, but it wasn’t until the Romans in about 100 CE that we have evidence of glass used as windows.” This is interesting for a number of reasons, not the least of which is that Rome’s oldest Christian basilica, Santa Sabina on the Aventine Hill (422-32 CE), uses Selenite (a natural translucent gypsum mineral) for its windows, imparting an ethereal glow to the interior.

Whether you are looking for a book that will educate you on the various styles of architecture, give you some insightful building facts, or serve as a guide to identify seminal stuctures worth visiting on future trips, Architectural Styles, A Visual Guide would be a good addition to your library.![]()

Thomas DeVoss AIA, is a LEED certified architect in Los Angeles who received a Classics degree at Georgetown before receiving his architectural training at Washington University in St. Louis.