By Teresa Bitler

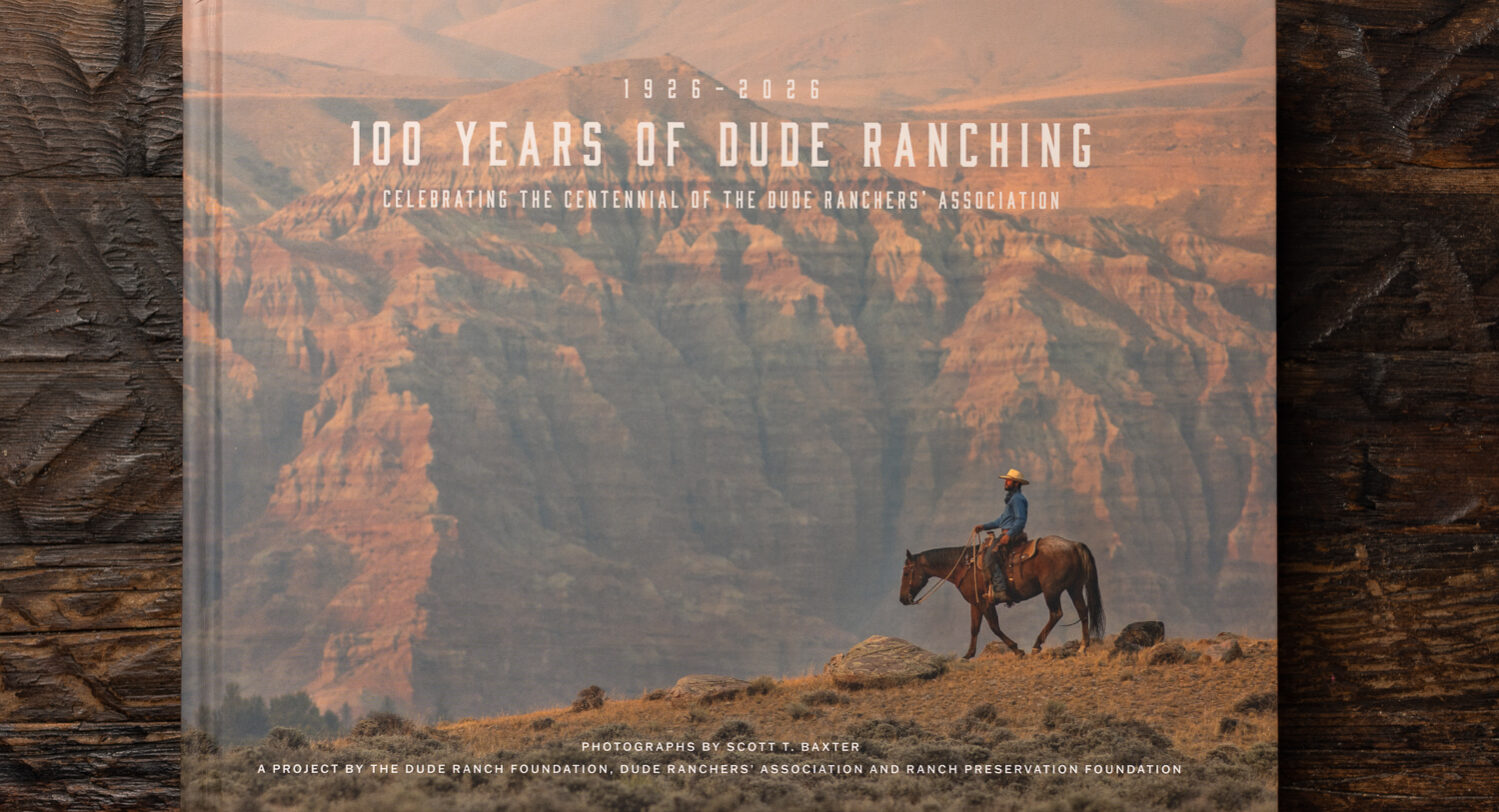

The cover of 100 Years of Dude Ranching—a coffee table-style book celebrating the centennial of the Dude Ranchers’ Association—captures the allure of a dude ranch vacation. In the photograph taken by Western photographer Scott Baxter, a cowboy rides across Wyoming grasslands against a backdrop of mountainous rock formations glowing pink in the sun’s low rays. Out of view, one can imagine guests following, taking in the epic scenery all around.

It’s that combination of the Western lifestyle and beautiful landscapes that keep generation after generation returning to dude ranches, according to Baxter and those involved with producing the book. Despite challenges facing the industry, such as increasing operating expenses and high-demand for ranch real estate, they agree dude ranches will continue to offer what people need—a chance to step out of their everyday world and into nature—for decades to come.

I agree with them. Roughly 20 years ago, my husband and I gifted our eight- and 10-year-old daughters a dude ranch vacation at a Colorado property that is now privately owned. At the time, we chose that ranch because it promised rides along the “Backbone of the Rockies,” a jagged grey sandstone spine overlooking a pine and shrub forest below.

But the horses and the natural beauty were only part of our experience. We reconnected. We ate meals together, sat around the campfire together and played games together. In short, we had the type of vacation I hope they’ll want to have with their own children one day and maybe even pass on to their grandchildren.

The rise of dude ranching

Dude ranches evolved from working cattle ranches, says Lynn Downey, who wrote the book’s history chapter. From their earliest days, cattle ranchers welcomed family and friends to visit. Among them were the Eaton brothers, who wrote enthusiastic letters back home, extoling ranch life.

Riders splash through Sonoita Creek at Circle Z Ranch in Patagonia, Arizona. Photo courtesy of Scott T. Baxter.

One of those letters appeared in The New York Times, where Theodore Roosevelt and other “dudes”—rich, fashionably-dressed young men—read it and inspired, traveled to Eatons’ and others’ ranch. While many of these dudes offered to pay, others did not, according to Downey, and the free room and board cut into the Eatons’ profits. Eventually, they decided to charge $10 per week to offset the costs.

In doing so, Custer Trail Ranch in Medora, North Dakota, because the first dude ranch. Still run by the Eaton family, the ranch changed its name to Eatons’ Ranch and relocated to Wolf, Wyoming, in 1904. It’s one of the 26 ranches profiled in 100 Years of Dude Ranching that predate the founding of the Dude Ranchers’ Association.

Bryce Albright, executive director of the Dude Ranchers’ Association, says the association’s founding in 1926 marks the actual birth of dude ranching because, before it existed, there was no real definition of what a dude ranch was.

“Some outfits and trail riding operations were calling themselves dude ranches,” she explains.

When ranchers formed the association, they set the standards that govern the industry today. To qualify for association membership, a dude ranch must offer a horse-oriented experience, be located West of the Mississippi River (or in the Canadian provinces of Alberta or British Columbia) and include meals, rooms and tips in its package price. Today, 90 ranches are members of the Dude Ranchers’ Association.

Dude ranches’ appeal

The idea for 100 Years of Dude Ranching started with the question of how many of those 90 ranches were around when the association was founded, says Bridget Brussels, the book’s project manager. Working with the Dude Ranchers’ Association, Dude Ranch Foundation and Ranch Preservation Foundation, Brussels assembled profiles of the 26 “centennial ranches” that existed in 1926 and supplemented them with historic photographs and Baxter’s images.

Looking at those 26 ranches from a historical context, Downey feels they were able to persevere through difficult times because they gave visitors an authentic experience. Guests could ride horses with ranch hands, and depending on the ranch, they could eat with the owner’s family. At night, around a campfire, they might even listen to the owner tell stories about the ranch, something she feels makes a big impact.

“Humans are hardwired for storytelling, and you get that at dude ranches,” says Downey, who is the author of American Dude Ranch.

She adds that dude ranches also survived because they can easily pivot to meet guests’ interests. For example, in 1926, guests were mostly privileged people use to indoor plumbing and maid service, but they gave that up to be “cowboys.” In contrast, today’s guests often want luxury bedding, five-star meals and even spas with some trail riding mixed in.

Russell True, whose True Ranch Collection owns six dude ranches including three of the centennial ranches—Black Water Creek Lodge & Guest Ranch in Cody, Wyoming; Kay El Bar Guest Ranch in Wickenburg, Arizona; and Rancho de la Osa in Sasabe, Arizona—has experienced that shift in real time. He says growing up on White Stallion Ranch, just outside of Tucson, Arizona, he watched guests entertain themselves in the evenings. They’d socialize and play cards.

“They didn’t need a cowboy singer,” he explained. “Today, people expect it. They want activities, entertainment and educational experiences.”

True’s ranches provide that. However, he’s quick to point out that, despite expectations, he doesn’t have trouble keeping guests engaged on the ranch. Even teens set aside their screens during the stay.

“At home, they don’t necessarily have a horse to ride or guns to shoot or trails to hike,” he says. “They don’t have axes to throw or rivers to fish. Here, they have the opportunity to do things that they can’t do at home, and it’s just so grand, so real, so different for suburban kids and adults. It just grabs them.”

Something for everyone

Dude ranches appeal to a broad range of people because they offer such a wide variety of vacations, according to Albright, who adds that part of the Dude Ranchers’ Association’s role is to match people with a property that best meets their needs. After determining their budget and length of stay, the association asks when and where they want to go.

At Mountain Sky Guest Ranch in Emigrant, Montana, riders enjoy views of Emigrant Peak at sunset. Photo courtesy of Scott T. Baxter.

If they plan to travel in the summer, the association directs them to northern ranches in states like Wyoming and Montana. (Fifty four percent of the Dude Ranchers’ Association members are located in those two states alone.) During the winter, dude ranches in Arizona open, offering a desert alternative. The difference between the locals can be striking in both scenery and activities.

For example, at True’s Tombstone Monument Ranch & Cattle Company on the outskirts of Tombstone, Arizona, guests help herd cattle through high desert grasslands peppered with boulders and crisscrossed by dusty trails. Or they can try archery and shooting, take a UTV tour through sandy, desert washes and cool off in the swimming pool. At night, they can learn to play Faro from an actor portraying Wyatt Earp before retiring to their room, a storefront in a recreated Old West town. (Tombstone Monument Ranch has only welcomed guests since 2009 and is not featured in the book.)

Compare that to Black Water Creek Lodge & Guest Ranch, True’s property in Cody, Wyoming, where guests stay in historic log cabins along the banks of the Shoshone River and Blackwater Creek, ride through the pine trees of Shoshone National Forest and tour Yellowstone National Park, 15 miles to the east. They can also fly fish for trout, whitewater raft and spend an evening at the Cody Nite Rodeo. True says it obviously has a very different feel than his Arizona ranches do.

In photographing the ranches, Baxter says the various levels of service stood out to him. Some ranches give guests a working cattle ranch experience with comfortable but basic accommodation and simple menus. Others offer five-star luxury. For example, in addition to horseback riding, Mountain Sky Ranch in Montana has a wellness center with spa services and yoga; a par 3 golf course and driving range; and a rope course.

The future of dude ranches

Despite the diversity of experiences, dude ranches face challenges. True says it’s becoming more and more expensive to run a dude ranch, and often, when they go up for sale, people purchase them as corporate retreats or private residences. Because rural real estate is so expensive, people who want to start a new dude ranch often can’t afford to, so the industry is dwindling.

However, dude ranches are typically located near beautiful places, he says, and people are always going to want to visit these areas, so he thinks they’ll always be a demand for this type of vacation. Add to that, dude ranch owners are resilient.

“It’s more than a business,” True explains. “It’s a lifestyle. It’s our identity. It’s our home.”

Albright, who like True grew up in the industry, agrees. The people who own and who work at dude ranchers are passionate about this way of life and will fight to maintain it for the next 100 years.

Largely, that is what 100 Years of Dude Ranching conveys—a love for the Western lifestyle, for nature and for family. It reminds readers of how beautiful the West can be and encourages them to slow down and enjoy time away from their screens. And those behind the book say, if it inspires some readers to take a dude ranch vacation, all the better.

Teresa Bitler is an Arizona-based writer who loves history and horses and never turns down an opportunity for a Western themed adventure. In her previous articles for East-West News Service, she’s explored the trend of dark tourism, followed in the footsteps of Bach in Leipzig and sampled Ibérico ham in Spain.