Yorkshire has fewer people than some of the southern counties, but there is no shortage of things to do in the green and pleasant north country. Photo by Nancy Wigston

By Nancy Wigston

England is the “green and pleasant land” of poet William Blake’s rhapsodic verse. Then there’s Yorkshire.

Yorkshire is the kingdom’s largest county. Its turbulent history rivals that of entire European nations. In the late Middle Ages, the city of York was second only to London in status and wealth. Today, Yorkshire’s rolling hills are dotted with great houses and the ruins of once-magnificent abbeys. The Transylvanian Count Dracula emerged from his coffin-ship on Yorkshire’s North Sea coast.

No matter the political, economic, or religious tumult that rolled northward, Yorkshire retained its stunning natural beauty. The Yorkshire Dales National Park and the North York Moors inspired several of the English-speaking world’s greatest novels. Some far-flung parts of Yorkshire have earned the moniker “God’s Own Country” for their curiously enticing bleakness.

North vs South or The Great Divide

Yorkshire began life as the seat of Roman operations in Britannia (71-400AD) and, for much of the 9th century, was home to Danish Vikings. That era collapsed with the arrival of the Normans, followed by the disastrous “Harrying of the North” by William the Conqueror’s troops. (The Danes lost, badly.) Still, Norse heritage lives on in place names like Whitby, Sheffield, Scarborough, and, according to some recent scholarship, in the very physiognomy of Yorkshire’s people.

Hold on a minute: the “Harrying of the North”? Not only is the term weirdly current but partly explains the “Great Divide” between England’s north and south. Popular Victorian novelist Elizabeth Gaskell’s social saga, North and South, set in Manchester’s Industrial Age, has been adapted for television three times. A recent guidebook by ex-Private Eye writer Ed Glinert takes visitors to Yorkshire’s “secret places,” among them the Aigin Stone on the Pennine moors. Six hundred years old, originally seven feet high, this pillar “marks the official boundary between the whole of the north of England and the whole of the south,” maintains Glinert. (Others may mistake it for a guidepost on northern hiking trails.)

The 600-year old Aigin Stone on the Pennine moors marks the official boundary between Southern England and the vast stretches of the North. Photo courtesy of wecometoyorkshire-yorkshire.com/

“Born and Bred in Yorkshire” is more than a slogan. It describes a proud, welcoming people with diverse roots and natural charm. “Thanks, my lovely,” a visitor might hear after a simple transaction, like buying stamps. “How’re you feeling, in yourself?” In The Secret Garden, Frances Hodgson Burnett’s 1911 children’s classic, an unloved orphan of Empire is sent to her uncle’s vast estate on the remote moors, where she not only brings a dead garden to life but also learns to “speak Yorkshire,” using “thee” and “thou” and “lads” and “lasses”—the last two still in common usage. Whole books are devoted to Yorkshire dialect and its peculiar figures of speech. “Any road” (anyway), best carry on.

When Catholicism Ruled

All England was Roman Catholic, until King Henry VIII (1491-1597) broke with Rome, then cast his eye on Church wealth, embarking on the dissolution of the monasteries. Today, among Yorkshire’s most awe-inspiring sights are soaring monastic ruins that loom dramatically from empty green fields. Fountains Abbey, England’s largest monastic ruin, near Ripon, speaks eloquently of Catholic England. Before Henry’s reign, Cistercian monks (1132-1539), farmed 500 acres, brewing sixty barrels of ale every ten days. Sixty monks worked alongside one hundred skilled lay people. When the monastery was plundered, stained glass was smashed and treasures taken. The whole was sold into private hands. But the Abbey still remains a giant presence with thick columns and a high tower, like the palace of a fabled monarch.

The immense ruins of Fountains Abbey near Ripon evoke the powerful presence of English Catholicism, more than five centuries after the destruction of the monasteries by King Henry the 8th. The abbey makes a perfect day’s outing from Ripon or York. An added sightseeing bonus is nearby Studley Royal Water Park. Photo by welsometoyorkshire-yorkshire.com

In the 18th century, John Aislabie, a disgraced Chancellor of the Exchequer, inherited land nearby and devoted his life to building Studley Royal Water Garden, with a moon-shaped lake, sphinxes, classical statues, cascades, and the whimsical buildings called follies. With a “surprise” view of the haunted charms of Fountains Abbey and a medieval deer park, the gardens have been admired for hundreds of years. Both Abbey and Gardens draw thousands to this corner of Yorkshire, the backdrop of many a film, rock video and mystery novel.

Near the Abbey is Castle Howard, for three hundred years the property of the Howard family. Castle Howard is Yorkshire’s newest architectural star, appearing in Bridgerton, Shonda Rhimes’ and Betsy Beers’ wildly popular take on Regency romance. Built on castle ruins in the 18th century, this Georgian attraction offers formal gardens, an obelisk, fountains, and fanciful follies.

Although strictly speaking not a castle, Castle Howard was built on castle ruins and earned its name for its size and majesty plus the wealth and power of the Howard family. The Carlisle branch of Howards who lived here were “recusant” or secret Catholics who resisted the Protestant Reformation. Familiar to fans of the Netflix hit Bridgerton, Castle Howard earlier debuted on television in Brideshead Revisited, based on the novel about a wealthy English Catholic family by Evelyn Waugh, himself a Catholic convert. Photo by visityorkshire.com

Lively Leeds

Just two hours by train from London is Leeds. Friendlier, cheaper, cozier than London, this party-hardy West Yorkshire city was founded in 1207 and grew famous for its woolen markets. A Royalist stronghold, it witnessed several English civil war battles. Its prominence in England’s 17th century cloth trade was unrivaled and by the 18th century, sellers of hardware, haberdashery, dairy products and livestock joined the 3,000 clothiers who came to Leeds on market days.

By the 1820s, town planners were frantically searching for new commercial space, and many of the city’s architectural gems date from the Victorian building boom. Visitors today can stay, eat, and shop in buildings that date from the city’s Golden Age. At Quebecs Hotel (1891), once Liberal Party headquarters (for members “possessing Liberal opinions”), guests enjoy tea and scones in the lounge, while keeping an eye out for Coldplay and Russell Brand, who also like it here.

In a party town like Leeds you have to rest when nobody’s watching. Photo by Nancy Wigston

When Alan Bennett, a Leeds boy without family money, secured a place at Oxford (unusual for the late 1950s), he joined Dudley Moore, Jonathan Miller, and Peter Cook in Beyond the Fringe, a satirical review that rocked audiences around the world. Today, Bennett is one of England’s most important playwrights, mining his roots for inspiration in hits like The History Boys. Bestselling author Barbara Taylor Bradford attended the same nursery school as Bennet, in the same Leeds suburb, before moving to the States. Although materially less well-off than the south, northern England has never lacked talent.

Or beauty. Under the soaring skylights of a Victorian arcade, with lacey ironwork and chic designer shops, a young man plays tunes on a sparkling white piano, while shoppers sip their lattes.

In 1884, shoppers at historic Kirkgate Market were surprised by the sign above Polish refugee Michael Mark’s stall. “Don’t ask the price, it’s all a penny.” Partnering with Skipton native Thomas Spencer, Mark’s novel approach to retail therapy rocketed their partnership to success. M&S remains a major presence, both in the UK and online. Kirkgate Market, one of Europe’s largest, reflects Yorkshire’s modern diversity. Food choices include chapatis, curries, Thai dishes, Yorkshire pudding and local cheeses (Wensleydale is superb). “Asian days” occur every Wednesday.

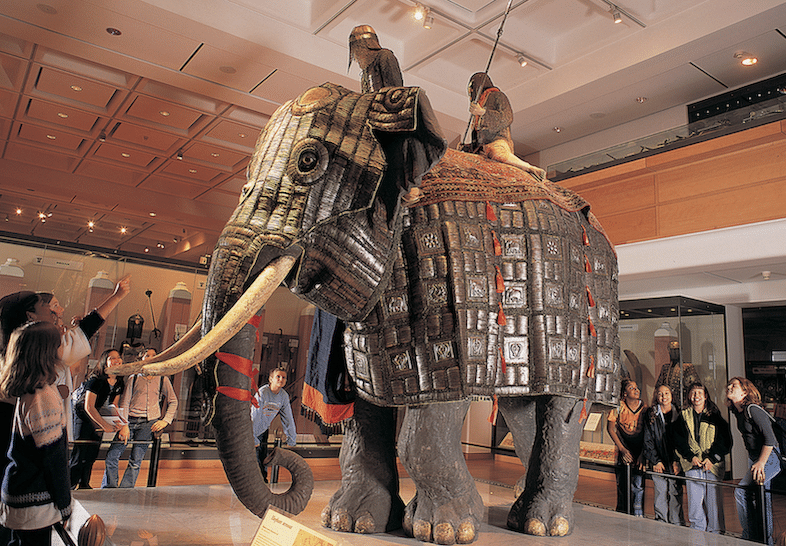

The Royal Armouries Museum is another must-see, with five galleries of arms and armor from ancient and modern times in Britain, Asia, and the American West, plus frequent live demonstrations. One Saturday afternoon, a family chats with a friendly Saxon warrior, his battle just concluded. Smiling, he talks to awed children about his chainmail, how heavy and hot it is, and how he longs for a nice cup of tea. War isn’t fun, but re-enactments can be, and the British do know how to put military history on show. A line by Beatle John Lennon–“Reality leaves a lot to the imagination”—appearing on a Royal Armouries wall, nicely captures the museum’s mood.

Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds. Photo by welcometoyorkshire-yorkshire.com.

Pubs and Clubs

In 1393, King Richard II declared servers of ale must be signed as such. Today, you’ll happen on some singular pub names, like York’s The Three-Legged Mare–not a lame horse but the medieval gallows that hanged three prisoners at once. The Tickle Toby honors an 18th century racehorse, while the Stumble Inn is self-explanatory. Clubs attract cutting edge bands but don’t forget their roots. Leeds’ The Chemic Tavern is named for Johnson’s Chemical Works, producers of sulphuric acid. A pint of Black Sheep Ale goes down nicely at The Pack Horse, The White Swan or The Cross Keys (the heraldic sign for heaven’s gate).

Up Hill, Down Dale

If you have time and love the paintings of David Hockney, explore Saltaire, a model village on the outskirts of Bradford, founded by Titus Salt for his textile mill workers in 1851. When the industrial age ended, Bradford native Jonathan Silver refurbished the derelict mill, creating a hub of eateries, craft markets and an art gallery featuring one of the largest collections anywhere of paintings by his childhood friend, David.

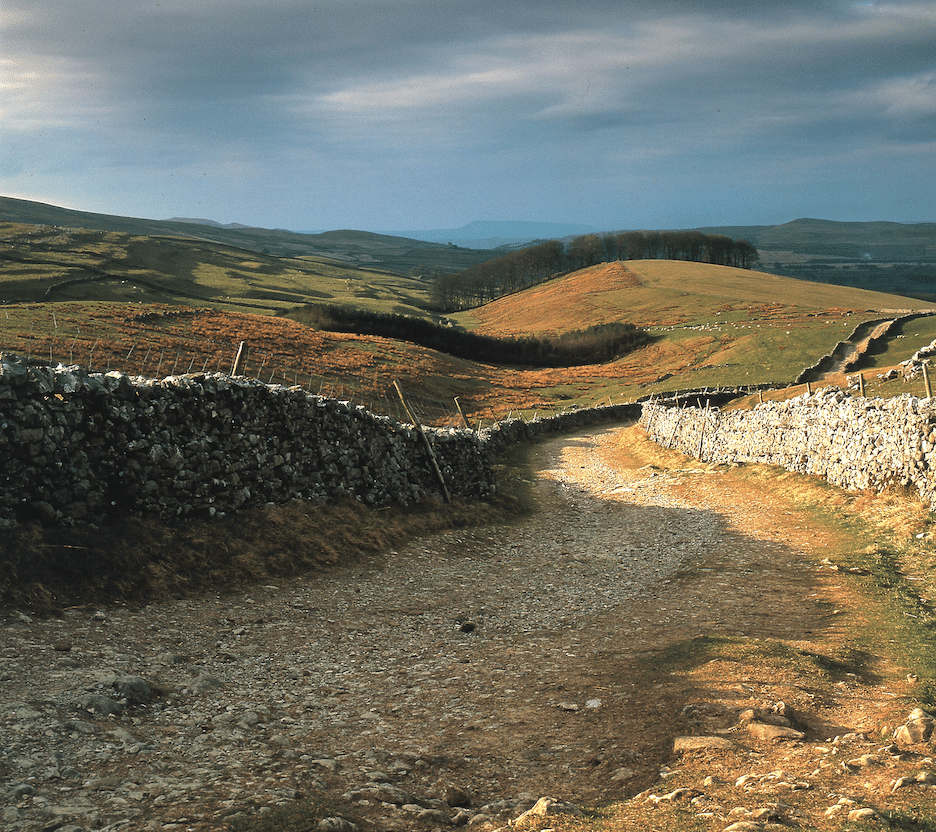

The two school friends used to hike the Dales together on weekends. The Yorkshire Dales (valleys) paint the most English of pictures: narrow country roads, stone walls, thick hedgerows, gently rolling hills, farms, and villages with “dales” in their names. If Nidderdale, with its emerald fields, cows, and sheep, seems familiar, it could be because All Creatures Great and Small takes place there and in neighboring villages. Real-life vet James Alfred Wight published eight books about his adventures in the Dales under the pen name James Herriot. His stories now enjoy an afterlife on television.

The undulating Yorkshire Dales are marked by thick hedgerows, stone walls and trails often filled with small herds of sheep. Photo by welcometoyorkshire-yorkshire.com

There’s a warm and welcoming feeling throughout The Dales. Stopping at The Yorke Arms near Nidderdale some visitors spot a fellow clad in plus-fours, shotgun at his side, like a grouse hunting character from the pages of a P.G. Wodehouse novel. Inside the excellent restaurant, grouse was on the menu, along with local wild mushrooms, pheasant, and rich chocolate desserts.

The Moors and Bronte Country

In one of literature’s great lines, “Reader, I married him,” plain Jane Eyre announces her change of status. Stashing his mad wife in the attic—an ill-advised move—caused wealthy Mr. Rochester to lose Jane, his child’s governess, at the altar. Much later, widowed and hurt, Rochester makes worthy husband material for our feisty heroine. An immediate bestseller in 1847, this story about a penniless but “free human being with an independent will,” who marries her Byronic hero, has never gone out of fashion. More than sixteen movies have been based on Charlotte Brontȅ’s tale, including an opera, an SCTV episode (Jane Airhead) and a 1943 zombie flick.

Charlotte’s London publisher was surprised, to put it mildly, to learn that his brilliant author was the diminutive daughter of a village parson. She’d used a male pseudonym, as did her sisters Emily (Wuthering Heights) and Anne (The Tenant of Wildfell Hall). Emily’s one novel–fraught with ghostly presences and doomed lovers—achieved lasting fame. How could a Yorkshire village produce three spinsters who wrote about passion?

Charlotte Brontë regarded Haworth as a “strange uncivilized little place.” But tourists from around the world find it comfortable and especially enjoy the Black Bull Pub. Photo by welsometoyorkshire-yorkshire.com

To find out, fans make a pilgrimage ten miles west of Bradford to Haworth, “a strange uncivilized little place,” in Charlotte’s words. Follow the steeply cobbled main street to the Old White Lion Hotel, a 300-year-old coaching stop. Rooms are smallish but nicely remodeled, offering storybook views of rolling farmland. Nearby, the Black Bull Pub frequented by the sisters’ dissolute brother Branwell continues to thrive.

The Apothecary where Branwell purchased his laudanum is now a cozy emporium, offering retro souvenirs, homemade creams, soaps, and candles. A cat dozes atop an antique display case. In Venables and Bainbridge Book Shop, purveyors of rare and used books, vinyl records and literary ephemera, the gentleman behind the counter happily chats with visitors about jazz.

The Parsonage Museum, though dour at first glance, exhibits Charlotte’s beribboned wedding hat, her set of pens, Emily’s bedroom, and the dining room where the children created their handwritten sagas, illustrated in miniature books. Oddly, the parsonage faces the ultra-gloomy church graveyard, where tombstones can be ten bodies deep. By evening—the perfect time for a Haworth ghost walk—rooks and bats fly overhead.

Yet the path behind the parsonage leads to the wild freedom of the moors. Striding toward Top Withens, fans reach a small stone ruin revered –against all logic—as the inspiration for Wuthering Heights, Emily’s tale about tormented love. “Be with me always–take any form—drive me mad,” pleads one character. “Wuthering” is Yorkshire for a strong, roaring wind, thought to affect the romantically inclined.

Buffeted by strong winds gusting across the moors, Top Withens inspired Emily Brontë to write Wuthering Heights. The stone ruin is on the Brontë pilgrimage trail tens of thousands follow throughout the year. Photo by bronte.org.uk

The moors occupy a 300-million-year-old delta in the mid-Pennines, with Bronze Age burial sites and unusually acidic soil. Trees are rare in this moody wilderness of bracken, and purple heather. The only living creatures besides humans appear to be birds and moorland sheep. So popular are Brontë country walks, that signs are bilingual: English and Japanese. A good thing, since tourists tend to lose the horizon–and their way. Follow the arrows to arrive safely at Brontë Waterfall where a chair-shaped rock commemorates the literary sisters.

The literary pilgrimage to Haworth and the rest of Brontë country usually ends at the Brontë Bridge and waterfalls. The Bronte Waterfalls are an easy walk from the Parsonage Museum and were a favorite destination for the literary sisters, who frequently walked their beloved moors. Photo by bronte.org.uk

Alice, Dracula, and Captain Cook: Whitby’s Mad Tea Party

A long-time favorite holiday destination with the English, Whitby specializes in the unexpected. La Rosa Hotel and Tea Room, for instance. Writer Lewis Carroll liked this location so much that he returned half a dozen times. Today’s owners pay homage to the creator of Alice in Wonderland, with fanciful nods to the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party. Peek into the dining room. A girl-sized doll wears what appears to be a cow’s head. Upstairs rooms in plush pinks, pale greens, are crammed with Victoriana. Breakfast arrives at your door in a picnic basket.

Whitby Abbey and the Church of St. Mary’s are reached by climbing 199 steps from the River Esk which flows past the seaport of Whitby. Ancient graves fill hilltop plots not covered by the 7th century abbey buildings. Photo by Nancy Wigston

Two cliffs, West and East, frame Whitby, which is divided by the River Esk estuary. The West’s riverside path is lined with fish and chips shops, palm readers, and ice cream shacks. Cross the old swing bridge to the east side and hang a left at 18th century Church Street. Among a jumble of sweet shops, dog-friendly cafes, and vintage clothing emporia you’ll see stores selling “Whitby Jet,” a shiny black carbon fashioned into jewelry. Romans liked jet jewelry, but jet really took off when Queen Victoria set fashion trends by wearing jet to complement her mourning attire, after Prince Albert’s death. Today, Victorian-era jet pieces fetch a queen’s ransom.

Church Street ends at the 199 Steps, where pallbearers carried coffins up to the Church of St. Mary’s. Ascend the steps to the old church and the ruins of 7th century Whitby Abbey, where English Christianity first blossomed. Abbess Lady Hilda was placed in charge of the grand new structure by Oswy, the Anglo-Saxon King of Northumbria, and it was here that a young Northumbrian monk composed the first poem written in English.

St Mary’s graveyard is moody even on a sunny afternoon, so it’s easy to understand why Whitby appears in Bram Stoker’s famous novel, Dracula. On a family holiday in the 1890s, the theatrical agent and novelist (twelve novels in all) fell under its spell. He spent hours in the library investigating famous shipwrecks. In 1897 his Gothic classic, Dracula, appeared and has never lost its bite.

The Transylvanian Count bounded ashore from his ghost-ship on Tate Hill Sands, disguised as a black dog. He climbed to St. Mary’s graveyard and found a sleepwalking innocent dozing on a bench and made her his first conquest. The undead Count and his lustful designs on Victorian womanhood caused a sensation. “A volume of horror,” wrote one reviewer. Who could resist?

One of the many seductive small shops in the villages and towns of Yorkshire, where visitors can bring home an enchanting memory of the region. Photo by Nancy Wigston

From 1930s vampire flicks to Tim Curry’s “sweet transvestite” send-up in 1975’s Rocky Horror Show to Sesame Street’s adorable Count von Count, Dracula has never gone away. Goth-attired fans periodically invade Whitby but are outnumbered by English pensioners happily walking their dogs and stopping for tea breaks in this canine-friendly town.

Whitby folk care little for Stoker. “He was Irish. He never lived here,” goes the refrain. Aside from the odd Dracula tour and a strobe-heavy “Dracula Experience,” Whitby’s dominant historical personality remains the very real Captain James Cook: adventurer, explorer, mapmaker extraordinaire. Cook apprenticed in Whitby during the 18th century whaling boom. Today his statue looms over West Cliff. Signposts indicate distances to Australia, Newfoundland, Indonesia, Hawaii, New Zealand—all places Cook sailed to during the great age of English exploration.

Son of the British Empire

Small, bright, stylish, the Captain Cook Museum occupies the restored riverside home of John Walker, the Quaker shipbuilder with whom young James apprenticed. Its collection of maps, exquisite botanical drawings, and artifacts from the Cook era is complemented by workshops in Indonesian batik-making. The museum manages to ooze intrigue while telling a riveting story.

James Cook did not survive the ambitions of those who urged him past his limits on his final voyage in search of the Northwest Passage. A volunteer at the Life Boat Museum tells curious visitors that by his third voyage, “Cook was not a well man.” The formerly kind, caring captain had turned erratic and in 1779 was killed by Hawaiians while attempting to kidnap their King.

The English love their dogs and nowhere more than in Whitby, a famously dog-friendly town, where even Dracula had the good sense to bound ashore disguised as a black dog. Photo by Nancy Wigston

His tale numbers among the seaside resort’s wonders: the spectacular Abbey, quirky St. Mary’s (where one vicar installed hearing trumpets so his deaf wife could hear his sermons), and the enchanting Whitby Museum with its Paleolithic finds. Yorkshire’s vastness requires time to discover. But before leaving the Whitby Museum be sure to see the desiccated human hand. Called the “Hand of Glory,” the withered appendage was blessed by Latvian gypsies, to bring good luck to pirates and criminals.

Yorkshire can seem timelessly quaint, but much has changed for the better. Pirates are no longer a problem.![]()

Nancy Wigston’s last story for the East-West News Service was on the city of York.