Elephant Nature Park founder Saengduean (Lek) Chailert crouches at the feet of FaaMai, a young female elephant that was born here in 2009. Lek administers the nonprofit refuge and rehabilitation center at Mae Taeng, north of Chiang Mai. Photo courtesy Save Elephant Foundation

By John Gottberg Anderson

A bull elephant is not a creature to be trifled with. One doesn’t go all Siegfried & Roy with tigers and lions, and even “Crocodile Hunter” Steve Irwin knew better than to provoke sharks and stingrays. From the time we were young, we learned not to tug on Superman’s cape, not to pull the mask off the Lone Ranger.

But when Asian elephant brothers Kham Meun and Dodo began reaching out for bananas, the last thing I wanted to do was turn tail and run. Not that I could have outrun them, anyway.

The pachyderms were young adults, not juveniles but still young enough (both in their 20s) to be frisky. Kham Meun had lost one of his tusks many years ago in an accident at a trekking camp, but the other ivory spike was very threatening. Dodo’s two tusks were smaller — about the size of small Christmas trees — but I’m sure no less lethal, should push come to shove. I wasn’t out to do either, neither push nor shove: The prodding came from their end, with trunks, not tusks.

The good news is that I was in a controlled environment. I was visiting Krieng Krai’s Karen Elephant Home in the hills of Mae Wang, a winding drive of a couple of hours from Chiang Mai in northern Thailand. I fed them bananas.

The Karen (kah-RENN) people — at least 6 million in Myanmar (Burma), perhaps up to 400,000 in Thailand — have raised elephants for many generations. Long before British colonists arrived in Burma in 1824, the Karen (and other hill tribes) had domesticated the largest of all land animals as beasts of burden, taking them from their wilderness homes for lives of labor. They pulled heavy teakwood logs from the forests of the upper Salween River, raised great stones to build ancient cities like Bagan, and led warrior kings into battle against rival Asian powers.

KhamLa, a 14-year-old female, sets the pace for a family of rescued Asian elephants at Elephant Nature Park. She and her natural mother, BaiTouay, following in the herd behind, were saved from cruel treatment at a trekking camp in another part of Thailand. Photo courtesy Save Elephant Foundation

No more circuses

The elephants don’t have to do that anymore. Nor do they perform as captive wildlife in North America and Europe, as they did for much of the 20th century, in P.T. Barnum or Ringling Bros. circuses. But history has done irreparable harm to the Asian elephant population. Whereas the wild population was once estimated to have been more than 100,000, it is now less than 50,000 across 13 countries, according to the World Wildlife Fund. Today about 15,000 are in captivity, with the greatest number of those in northern Thailand. (Asian elephants do not grow as large as their more numerous African cousins; they have smaller, rounder ears and females cannot grow sizeable tusks.)

Ethnic Karen are the largest in number of Thailand’s baker’s dozen hill tribes (chao khao). Krieng Krai’s camp is not far from Doi Inthanon National Park, which surrounds its namesake highest peak (8,415 feet) in Thailand. Many Karen live in foothill villages, where Krieng Krai and his wife, Phatbun, have developed an environmentally sustainable farm of terraced rice fields and vegetable gardens, shifting away from the traditional slash-and-burn agriculture practiced by many hill tribes. They both were born and raised here, Krieng Krai only leaving for high school as a teen but quickly returning.

His wife’s family, he told me, has raised elephants for at least 100 years. Today they are the caretakers of three elephants: the two brothers and their adoptive aunt, Mae KaPha. The young males had lost their elderly mother, Mae Thor Khor, to natural causes a few years earlier, and Mae KaPha’s own offspring had died when she was 3 from a virus. Elephants are social creatures, like humans, and a match was made early this year to bring them together … for purposes of companionship, not romance. So far, it’s been a success.

The ‘elephant whisperer’

There are many dozens of elephant “camps” in the vicinity of Chiang Mai. None is larger than the Elephant Nature Park near Mae Taeng, where two weeks earlier I had spent a full day in the company of founder Saengduean (Lek) Chailert, 64. She is — and all superlatives are justified — a remarkable woman.

A pack of Asian elephants shows its affection for founder Saengduean (Lek) Chailert at Elephant Nature Park. The refuge is home to 121 elephants, most of them rescued from abuse or neglect, along with scores of other animals. Photo courtesy Save Elephant Foundation

Lek may be smaller than 5 feet tall in stocking feet, and she cannot weigh more than 95 pounds. She is utterly dwarfed when she is surrounded by a half dozen six-ton elephants. But this is her comfort zone. They are her best friends and her almost constant companions.

Born in a tiny village in northern Thailand, Lek is known far and wide as “the elephant whisperer.” Her grandfather was a shaman, and she grew up watching him care not only for community members, but also for injured elephants and other wild creatures using traditional remedies. As she grew, Lek considered elephants an integral part of her family, much as many Westerners embrace their dogs and cats. She shuddered to witness the abuse that her proboscid “sisters and brothers” endured in heavy labor and in performing shows: shackled, sometimes blinded, and beaten until they bled. Many young elephants were taken from their mothers long before reaching maturity. Tusks were removed for their ivory and the wounds left to fester. Lek worried for their physical and mental health.

After graduating from Chiang Mai University, Lek dedicated her life to fighting for animal rights and putting an end to animal abuse. She founded Elephant Nature Park (ENP) as a refuge and rehabilitation center for elephants, the first of its kind in Asia. She later established the nonprofit Save Elephant Foundation (SEF). Lek was passionate about rescuing “damaged” elephants and campaigning against “elephant crushing,” a practice by which baby elephants were restricted in cages.

An animal sanctuary

When a documentary about her work inspired a PETA boycott of Thailand, the Thai government and others in the elephant tourism industry responded by attacking the park and Lek’s reputation. But Lek persisted. By 2004, ENP relocated its nine rescued elephants to new land in the Mae Taeng valley northwest of Chiang Mai and invited visitors to come and help care for the elephants. Soon guests were paying a modest sum to stay for up to a month.

LekLek, left, and her mother, MohLoh, have stayed close since their joint rescue from a trekking camp in early 2024. Before being welcomed to Elephant Nature Park, many elephants were subjected to cruel disciplinary actions intended to control their behavior. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

That model remains in place today, and ENP — which now occupies 250 acres — has inspired the creation of newer ethnical elephant parks across Thailand (in Kanchanaburi, west of Bangkok; Surin, near Cambodia; and Phuket Island in the south). More than a dozen other parks in Thailand, Cambodia, Laos and even India also are associated with the Save Elephant Foundation. The number of elephants at ENP has grown to 120. Since 1998, Lek has rescued more than 200 elephants, mainly purchasing them from abusive situations with help from a network of international donors. The park also provides sanctuary to about 650 dogs; 2,000 street cats; water buffalo, cows and wild boars from slaughterhouses; rabbits and birds from science labs.

“How many countries have this beautiful animal?” Lek asked rhetorically as we sat in the open-air pavilion where ENP welcomes a few small groups of visitors each day. “Now we have about 45,000 (Asian elephants) left in the world. For me, they are the treasure. If we want to know what elephants want, we should ask our own hearts. They want to share our planet, same as everyone. Let them live with dignity.”

Lek considers education to be the primary goal of her foundation, globally as well as locally. National Geographic and Animal Planet have featured her work in documentary films; the Ford Foundation and Time magazine, among many others, have praised her conservationist ethic. She has traveled extensively and uses her fame to advocate and to garner charitable contributions from deep-pocketed donors.

Herd members follow Namthip across a dusty plain near the Mae Taeng River. “No one understands elephants like elephants understand each other,” said Elephant Nature Park founder Lek Chailert. Photo courtesy Save Elephant Foundation

“Elephants are meant to be in the wild and be independent,” she said. “At ENP, we don’t use elephants for entertainment. There is no dancing, performing, riding. Our place is education for tourists, who can see how we feed and nurture them. Visitors are able to meet the elephants and learn about their past lives.” Indeed, photo panels describe the personal histories of many of the longer-resident animals, including a pair that lost their lives during flash floods driven by Typhoon Yagi in October of last year. They are still mourned.

‘We give them a family’

After a robust vegetarian buffet lunch, Lek and I donned gumboots to wade into a red-clay quagmire that had begun to form in a light drizzle. Almost immediately, a family group of seven or eight elephants perked up. It was the fastest I saw them move. A young female named FaaMai — who was born at ENP in 2009 and has never known another home — led her companions to flat land near the Mae Taeng River where Lek waited with me to greet them. They nuzzled her gently with their supple trunks.

“No one understands elephants like elephants understand each other,” Lek told me. “We give them a family.” Quietly, she noted: “Many elephant camps still shackle and beat them.” The opportunity to ride an elephant entices many Asian tourists, especially Chinese, she said, so it’s difficult to dissuade many camps from halting this offering — although her “Saddle Off!” outreach program supported by Asian Elephant Projects has had success with independent camps. ENP stopped allowing visitors to bathe the elephants about 10 years ago; during Covid, the park also brought an end to tourists’ feeding the animals. This was partly to minimize transmission of germs, but also to reduce any stress the creatures might absorb from hesitant visitors.

We walked to a central shelter beneath a large fig tree, where several mahouts — elephant keepers, one per animal — perched while keeping a close eye on their charges. They were mostly men in their 20s and 30s who, like Lek, grew up around elephants. A majority were Karen and Shan tribespeople from neighboring Myanmar (Burma), Lek said. “They give the elephants love, monitor their diets and sanitation, but never use a hook,” Lek said. “They are trained to be honest.”

LekLek shares a tender moment with her mahout. Elephants form strong one-to-one bonds with their caretakers, most of them Karen and Shan hill tribesmen who grew up as children with the great beasts. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

In many cases, mahouts are the sole source of income for their families. Lek now offers them an opportunity to sell their crafts, such as elephant wood carvings, at ENP’s gift shop and elsewhere. She also works with local communities, purchasing food, hiring villagers, creating work for unskilled women and even restoring forests.

We strolled past the medical facility, where a team of resident veterinarians live and work, and to a set of open shelters where elephants may curl into piles of soft sand for comfortable sleep. And we passed a contained area where a few cranky oldsters (the elder matron is now 95) and cantankerous young bulls can’t offer attitude to more mild-mannered elephants. By design, the ENP herd is heavily female.

At the Karen Elephant Home, Kham Meun leads his brother across a stream that flows from Doi Inthanon, Thailand’s highest peak (at 8,415 feet). Elephants, like humans, are social creatures, and most prefer company. Photo courtesy Asian Elephant Projects

Living with elephants

It takes a village to minister to 10 dozen elephants. Lek could never achieve her purpose alone. Paid staff and a legion of volunteers run day-to-day operations. The “Living with Elephants” program invites tourists to stay for a week, participating in elephant care and food preparation, contributing to facility maintenance. The Save Elephant Foundation maintains a food bank to support the dietary requirements of rescued elephants. During the Covid crisis, the food bank helped to provide food to about 2,000 elephants at camps and projects around Thailand. As the great animals eat 10 percent of their body weight daily (about 600 pounds), that’s a lot of food.

If riding the animals, or even showering with them, incites stress in elephants, what’s a visitor to do? It’s largely an exercise in observation — of how an elephant lives in an environment that resembles its natural habitat. English-speaking guides walk groups (not busloads) of visitors through the grounds. The elephants mostly ignore their intrusions as guides encourage them to maintain a safe distance.

Now Lek is developing a new highland home for her elephants in a semi-wild, forested setting with a waterfall — where elephants can roam totally free, with no humans on the ground except caretakers. An overhead skywalk, under construction, will enable visitors to view the herd without interfering. “This has been my dream for a long time,” she told me. “My real dream is a new home in 2028.”

I followed Lek back to the gathering area where FaaMai first greeted us. The beasts followed her to a central area where mahouts were preparing a feast of corn, cucumbers, pumpkins, watermelons and bananas. Lek moved directly to the center of the throng.

Visiting American businessman Tudor Tiedemann was rapt as he watched. He was beside himself, like a schoolboy at his first big-league ball game, when Lek asked him to join her. A veteran of the nonprofit funding wars, she knew exactly what she was doing. “What should I do?” he asked her. “Hold out the bananas,” she said. “The elephant will wrap her trunk around it and put it in her mouth.” Mission accomplished.

Later, Tiedemann and a friend stood on a bridge over the river as another young female, KhamLa, led a herd of seven elephants through the silty stream on a daily stroll. The New Yorker was still trembling with delight. “I’ve never seen anything like this!” he exclaimed to me. Then he turned to his friend and declared: “Well, they’re going to get some money!”

And Lek will be one step closer to her highland sanctuary.

Krieng Krai exhibits a colorful buffet meal: a smorgasbord of watermelons, sweet potatoes, cucumbers, carrots, pumpkins, corn cobs and husks, and of course bananas. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

Home in the hills

Krieng Krai’s Karen Elephant Home offers a decidedly different experience. Whereas at ENP, I was able to feed a few docile female elephants under the gaze of the owner herself, Krieng Krai’s joint — as home to only three of the great beasts — allows a little more interaction.

Accompanied by SEF volunteers Kris from Australia and Diana from Colombia, I made the long drive into the Doi Inthanon hill country, traveled down a precipitous gravel road, disembarked from a sturdy van, and crossed a shaky footbridge over a slow-flowing stream to a pond of blossoming lotus flowers. At the top of a small hill, an equally small sign announced the Karen Elephant Home. An expanse of terraced rice paddies extended well to the south. A village — a couple of dozen homes and a Buddhist temple — decorated a hillside to the east. But my attention was drawn by a discreet movement to a slope on the west. I spied elephants.

Kham Meun, Dodo and Mae KaPha share an elaborate meal of fruits and vegetables at Karen Elephant Home. Most of the crops come from Krieng Krai’s own garden or are purchased from neighbors. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

The brothers, with one tusk and two, were halfway up the hill, foraging amid tall grass about 30 yards apart. The matron was near the bottom of the hill in a thicket of broadleaf shrubbery.

Dogs and elephants seem to get along well, so it came as no surprise that as we took in the view from the paddies, we were joined by Krieng Krai’s dog. Soon, he led us to the craft shop, where Krieng Krai had found a side hustle turning dried elephant dung, molded and baked, into sculpted souvenirs. Even with only three elephants, there was plenty of dung to go around.

After a lunch of noodles and vegetables, it was time to watch the elephants enjoy a feast. In a grassy expanse near the stream, Krieng Krai and the three mahouts (one per elephant) had laid out a smorgasbord that included watermelons, sweet potatoes, cucumbers, carrots, pumpkins, corn cobs and husks, and of course bananas. Then the honored guests were ushered in, beginning with Mae KaPha, the elder female. Kham Meun followed, then Dodo. The boys at first seemed a little timid, not wanting to encroach too far into Mae KaPha’s dining sphere, but soon were happily indulging their appetites each beside the others.

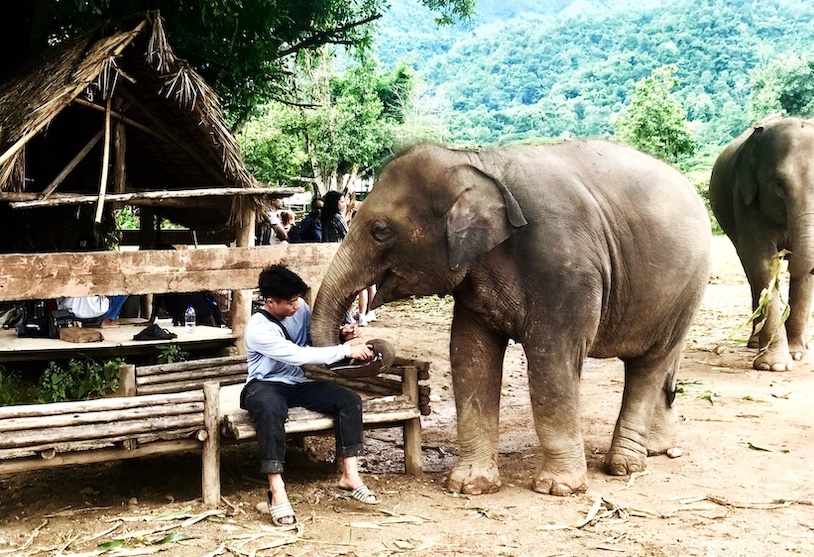

As the elaborate spread disappeared, my companions and I climbed a hillside to an observation platform. Having now finished their main course, the two young bulls took notice. We had more bananas. Almost before we knew it, their periscope-like trunks were extended in the hope of more treats. We could hardly say no.![]()

John Gottberg Anderson has covered Southeast Asia for the East-West News Service since 2019. He is a widely published American travel journalist and educator, a former Los Angeles Times news editor and the author of 24 books. His previous stories included Cambodia’s southern coast and Vietnamese religion. He presently lives in Chiang Mai, Thailand.