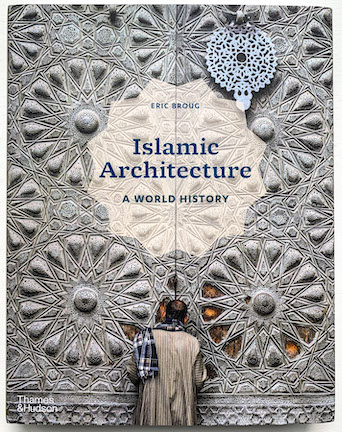

Islamic Architecture: A World History, Eric Broug

Publisher Thames & Hudson | Reviewed by Charles Cecil

Islamic Architecture: A World History by Eric Broug

It will be a long time before another publication equals the beauty and quality of this one. Eric Broug is previously known for his publications teaching the art of Islamic geometric design. With an MA in the history of Islamic art and architecture from the School of African and Oriental Studies in London, he has now turned his attention to surveying the worldwide, tangible heritage left to us, and continuing to grow, by artists, architects, and engineers inspired by the Islamic tradition.

In addition to covering fourteen centuries of Islamic architecture, this book also inspires travel, stimulating our desire to actually see these many structures, each situated in its own environment.

The quality of the photographs in this work is the first thing that strikes the eye. Broug claims to have viewed more than half a million photos while selecting the 300 or so included in this volume. Many of the greatest works of the Islamic world are already well known. Broug casts his net more widely, drawing our attention to many lesser-known architectural marvels. He draws our eye to examine the intricate details and delicacy that characterize many Islamic structures. “I have let the images in the book do most of the talking,” he says.

The six main chapters of the book are devoted to different geographic regions of the world. Each begins with Broug’s commentary, noting the historic highlights of the region plus the more recent contemporary trends. These introductions are written in a relaxed, colloquial style, neither heavy nor academic, but leaving no doubt as to his mastery of his subject. A short paragraph captions each photo, giving us the essential information (name, date of construction, and historical significance). The print for these captions might have been just a bit darker for readers whose eyes need a little help.

This is a book of “firsts”, “mosts” and “onlies.”

- Islam’s earliest surviving monument, the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. This structure is not a mosque. It covers the exposed bedrock from which Muhammad is believed to have ascended to Heaven. This same rock, called the Foundation Stone by the Jews, is also believed to be the place where Abraham was prepared to sacrifice his son Isaac.

- Islam’s first mihrab, the Mihrab of Suleiman in Jerusalem, in the B’ir al-Arwah, under the Dome of the Rock. This small cave, the “Well of Souls”, lies under the Dome of the Rock and is a place of prayer. A mihrab is an indentation, normally in the wall of a mosque, indicating the direction of Mecca, toward which Muslims are supposed to turn when in prayer. The mihrab of Suleiman dates from the seventh or eighth century.

- The only mosque without a qibla (indicating the direction of prayer towards the Kaaba), Al-Masjid al-Haram, in Mecca.

- The oldest minaret in Islam, in the Mosque of Kairouan, Tunisia

- The most controversial construction: the building of a Roman Catholic cathedral in the middle of the Great Mosque of Cordoba, Spain in the 16th century, after the Muslims were expelled from Spain.

- The oldest mosque in Thailand, built in 1634 entirely of wood, without nails.

- The first mosque in Denmark, built in Copenhagen in 1967, with no minaret.

- Also included is Syria’s most beautiful minaret, the 11th-century Seljuk (Turkish-Persian) addition to the Great Mosque of Aleppo, destroyed in Syria’s civil war in 2013. Broug also shows us the Uyghur mosque in Xinjiang, China, built in 1540 and purposely destroyed by the Chinese government in 2019.

The book goes beyond the usual concentration on the architecture of buildings serving Islamic religious functions—mosques, madrasas (religious schools), mausolea—to show also how Islamic features have inspired structures serving non-Islamic functions, such as Italy’s Amalfi Cathedral, the Doge’s Palace and the Basilica of Saint Mark in Venice or the Serrablo churches of northern Spain dating from the tenth century.

Not all “Islamic architecture,” Broug points out, is designed by Muslims. The Museum of Islamic Art in Doha, Qatar, was designed by I.M. Pei. Frank Lloyd Wright designed California’s Marin County Civic Center. The Shriners’ Medinah Temple of Chicago, which later served as a Bloomingdale’s Department Store, was designed by Chicago architects Huehl and Schmid. Hundreds of synagogues around the world employ a style known as “Moorish Revival.”

Doha, Qatar. Museum of Islamic Art, designed by architect I.M. Pei. Photo by Charles Cecil

In many ways, this book serves as an inspiring guide for future travels. Broug notes that in recent decades the rulers of the Arabian (Persian) Gulf emirates have displayed a “boldness of vision” in commissioning new constructions, hiring the best international builders and architects to achieve these ends. Anyone traveling to the Gulf region should seek out these mosques and other structures. Viewing them can add immeasurably to the enjoyment of a trip. One could plan a tour of architectural highlights starting at the top of the Gulf, in Kuwait, at the Sheikh Jaber al-Ahmad Cultural Center, going next to the Beit al-Quran Museum in Manama, Bahrain, then to Doha’s Museum of Islamic Art and the College of Islamic Studies at the Hamad bin Khalifa University. In Abu Dhabi the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque is incredibly beautiful and offers daily tours for all visitors. And who could resist visiting the Louvre of Abu Dhabi, knowing also that virtually unlimited funds will always ensure the presence of world-class works of art? Dubai (both for Islamic and other ultra-modern constructions) is a convenient stopping point en route to Sharjah’s “Flying Saucer” cultural center and the Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque in Muscat, Oman.

Broug apologizes for the brevity of the Asia Pacific chapter, noting that little has been written to document the rich architectural heritage so often influenced by indigenous design traditions that depart from what is usually considered “Islamic architecture.”

His photos show us the strength of these local influences in both historic and contemporary structures. This work also illustrates a number of lesser-known adobe mosques from the African Sahel region. “Women in Islamic Architecture” contains short commentaries noting the role played by 16 notable women who sponsored or oversaw the construction of mosques, madrasas, or other construction projects.

A concluding chapter on the Islamic practice of establishing a charitable religious endowment (waqf) uses the 15th-century waqf of the Timurid poet, statesman, and scholar Mir Ali Shir Nava’i who lived in Herat in what is now western Afghanistan. His 1481 text, Waqfiya, lays out the instructions for the use of the revenues accruing from his many properties. Broug concludes with a short glossary, a list of Islamic dynasties, and an extensive bibliography.

Unfortunately, the Picture Credits section is almost useless as a reference tool, with entries arranged in an indecipherable order, no sequential listing by page number, making it impossible to determine the source if one wants to know who provided an image found on some page in the book. A good editor should have corrected this.

Anyone with more than a passing interest in the subject will want to add this work to their library. There have been other books about Islamic architecture. It will be hard to find one with a better collection of beautiful photos and a well-written introduction to the subject. You’ll want to include visits to these constructions in your travels. ![]()

Islamic Architecture: A World History

Eric Broug, Thames & Hudson

336 pages, 327 illustrations, $75.00

ISBN 978-0-500-34378-4

Ambassador Charles O. Cecil’s 36-year diplomatic career included assignments in ten Muslim countries. He now devotes himself to international travel writing and photography. View his images at www.cecilimages.com