Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors being performed at the Globe Therter. Photo courtesy of Farelight Productions

She was the last monarch in the Tudor dynasty. During the 44-year reign of Queen Elizabeth I, England experienced the flowering of her Renaissance and became a world power brimming with prosperity and creativity. Auburn-haired, single, clever, courageous—and Protestant—Elizabeth I ascended the throne in 1558, following her Catholic sister Mary and her much-married father, Henry VIII.

TAKE ME TO THE RIVER

During her reign, new products—from spices and rum to tobacco and sugar—poured into London from her colonies in the Americas, and manufactured British goods—textiles, ironware, weapons—were exported in turn. The Port of London became one of the busiest in the western world—thanks to piratical “Sea Dogs” like Francis Drake and John Hawkins and their daring raids on Spanish galleons. One London visitor often counted a hundred ships and barges crowding the River Thames.

Urban life centered on the Thames, with numerous private boats—including rare glimpses of the Queen in her lavishly decorated barge. Three thousand “watermen” offered taxi service to various river stops. Soon London streets, never praised for their cleanliness, had a traffic problem. The arrival of horsedrawn “hackneys” from Europe eased things somewhat — evolving into today’s iconic black London cabs. The capital’s population increased from 50,000 to 200,000 during the 16th century.

In perhaps the most famous portrayal of Elizabeth I, she is crowned, and clad in her Coronation robes, holding the symbols of monarchy. This portrait today hangs in London’s National Portrait Gallery.

DIVERSITY AND CHANGE

The city began to look different, too. As the mercantile class prospered, they built splendid riverside mansions, while French protestants (Huguenots), mostly skilled professionals, flocked to London after the 1572 St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. Rural populations fled to the city seeking work, after previously open fields were enclosed by private owners. Apprentices trained by various guilds in every imaginable trade or craft—from haberdashery to goldsmithing–earned decent incomes. Actors and playwrights became shareholders in theater companies and could make impressive salaries if their plays proved popular. William Shakespeare applied for and was granted a family crest, reflecting his leap in social status from an “upstart crow” as university playwright Robert Greene called him, to a wealthy landowner in his hometown of Stratford-upon-Avon. The Medieval Age had ended, and times were changing.

No better proof that England was on a roll came in 1588, when English naval forces defeated the powerful Spanish Armada, signifying a bright future for a people weary of wars and religious strife. It was a time of creativity, marked by a thirst for the fresh and new. Portrait painting—both life-sized and miniatures-became popular with aristocrats and landed gentry. Playwriting appealed to all Londoners, whatever their class.

As many as 15,000 theatergoers attended plays every week, when the theaters weren’t closed due to plague outbreaks or censorship. Luckily, the Queen loved theater (she also enjoyed bearbaiting, as grisly as it sounds), although she demanded that the players entertain her court at lavish White Hall Palace. Tradition has it that Elizabeth herself suggested that Will Shakespeare follow his hit, Henry IV, Part One, with another play showing John Falstaff in love. The result was The Merry Wives of Windsor, the comedy now playing to packed houses at Shakespeare’s Globe.

Queen Elizabeth I relied for her safety on the brilliant spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham, founder of the Secret Service. Her portrait and his are on display in the National Portrait Gallery’s Tudor Gallery, along with many of her courtiers, including Sir Francis Drake. Photos by Nancy Wigston

DANGEROUS DAYS

Despite the economic boom and relative stability, Elizabeth, unmarried and childless, lived in tempestuous times and could not risk attending entertainments outside her secure circle. Plots against her were rife, and her security team, headed by Sir Francis Walsingham—founder of the secret service, who ran the sovereign’s spy and double agent network—made sure the ruler of the kingdom remained safe. Heads of traitors were displayed on spikes on London Bridge, and smugglers hung from bridges for three tides until they were removed. A young Elizabeth had been kept in the Tower for eight weeks—detained when her sister Mary was on the throne—until she was released under house arrest at Hampton Court Palace. (Mary relented, making Elizabeth her heir.) In her final years, as the question of succession grew more pressing, the Queen looked the other way when her personal physician, whom she knew was innocent, was convicted of plotting to poison her. However, when her handsome young favorite, Lord Essex, returned to England after his disastrous military campaign in Ireland, he tried to mount a rebellion against her. His treason cost him his head.

FACE VALUE

As Queen, appearance played a vital PR role in maintaining Elizabeth’s popularity—“Good Queen Bess,” or “The Virgin Queen” were her nicknames, and after the Spanish defeat, “Gloriana.” Portrait after portrait shows her adorned in luxurious silks, furs, lace and pearls with precious jewels conspicuously present. One painting shows her wearing a dress embroidered with eyes and ears, in recognition of her spy network.

A serious bout of smallpox at age 29 left her face scarred. But in public appearances, the Queen always seemed flawless—her face painted with white lead-based make-up, her cheeks dotted with toxic red vermilion. As she aged, her teeth grew discolored, and her hair thinned. Known to be as vain as she was royal, some court ladies flattered her by imitating her greying teeth. Elizabeth avoided mirrors as she grew older and took to wearing wigs.

Today’s House of Windsor carries on another tradition of granting Royal Warrants to favored businesses. Queen Camilla’s longtime hairdresser and her cosmetic products receive a Royal imprimatur, as do champagne importers, UK carpet makers, and milliners. A souvenir bottle of port becomes much more impressive when it bears the Windsor equivalent of a Michelin star.

The Great Gatehouse at Hampton Court Palace under a blue sky. Visitors can be seen in the foreground. Photo courtesy of Historic Royal Palaces.

TUDOR LONDON THEN AND NOW

What remains of Tudor London today? Although two-thirds of the wooden city would succumb to flames during the Great Fire of 1666, which also cleaned out plague-carrying rats. Yet today, a number of Tudor buildings remain. They include the Clink Jail (now a museum), the Seven Stars Pub (close to Shakespeare’s original London digs), a version of the George Inn, with its balcony and coaching yard, the Royal Exchange (modeled on the Bourse in Antwerp), and castles like sumptuous Hampton Court, west along the Thames. Flames destroyed the ancient wooden spire of St Paul’s Cathedral, soon redesigned by Christopher Wren in neoclassical style. Blackfriars Bridge still connects north and south London. But structural imperfections made it impossible to save the original London Bridge, which now resides in Arizona.

Fancy a trip along the Thames? Boats (including Uber-taxis) leave a variety of docks for destinations like Hampton Court Palace. Some offer dinner service. Fish are swimming in the Thames again—and, of course, the solid stone Tower remains, a showplace for crown jewels rather than a prison. Since Henry VII’s reign, Yeoman Wardens, called “Beefeaters,” have stood guard in their vivid uniforms, protecting the monarchy. When poet, diplomat, and soldier Sir Philip Sydney famously wrote “Sweet Thames, run softly till I end my song,” he was a sonneteer second only to Shakespeare in public estimation. He might be pleased that the river today resembles his fond vision so closely.

Yeoman Warders giving a tour to members of the public at the Tower of London. Photo courtesty of Historic Royal Palaces

BANKSIDE

In Elizabeth’s day, Bankside was the heart of the entertainment quarter. South of the Thames—legally, therefore, offering pastimes outside the city’s laws–Bankside was where the action was. Though interrupted at times by plague and eventually stopped by Puritans, by 1600 new theaters—the Rose, the Curtain, the Globe, and more–had sprung up in raunchy old Southwark Borough, fertile ground for writers of the “middling” classes like Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson. Their works entertained audiences of up to 3,000 in a single afternoon with dramas featuring both foreign and domestic tales. A penny dropped into a secure box (the “box office”) bought the “groundlings” a place to stand, close to each other and the stage. A few pennies more got wealthier patrons seats in the upper tiers—the structure inspired by Roman amphitheaters. If a new play was not available, nearby venues offered crowd pleasers like bearbaiting and cockfighting.

Bankside was chaotic, cluttered with houses of ill repute (“stews”) that jostled next to taverns where wine was served, gambling dens, and ale houses (“pubs”). Street sellers hawked fresh oysters, while the less fortunate begged for coins or resorted to picking pockets—these were the so-called “cutpurses.” Playwright Ben Jonson disparaged Bankside as full of bawds and low-lifes—this from a man who killed an actor in a duel, then escaped hanging because he could read the Bible in Latin. The medieval law called Benefit of Clergy got him released, but only after having his thumb branded.

Nobles might brave the filthy streets on horseback while avoiding the horse-drawn carts bringing food to Borough Market (a tourist attraction today). Playwrights, musicians and circus performers entertained the Queen at stunning White Hall Palace (destroyed by fire in 1669).

SURVIVORS

Ye Olde Mitre Pub’s warm interior is as popular today as it was more than 400 years ago. Slow down or you’ll miss its narrow entrance! Photo courtesy of Ye Olde Mitre Pub

The Seven Stars pub (1602) faces the Royal Courts of Justice in Westminster. It’s a survivor of the Elizabethan era that offers “well-kept beer,” home cooking, and “olde worlde” charm that isn’t, as the Brits say, “twee,” or unbearably cute. Ye Old Mitre Pub (1546) in Ely Court can be found, with some effort, down a narrow passage that links Ely Place and Hatton Garden, London’s diamond trading center. It’s documented that Queen Elizabeth danced around the pub’s cherry tree with Sir Christoper Hatton, her close advisor. In thanks for his service, Hatton was given a house in nearby Holborn. English fare like toasted cheese sandwiches, pork pies, and scotch eggs are served along with Fuller’s draft beer.

A DARING AGE

Elizabeth’s London was marked by the public’s perception of the Queen’s own sense of independence and daring. An intriguing story told in James Shapiro’s A Year in the Life of Shakespeare, concerns a company of actor-shareholders called The Lord Chamberlain’s Men. On Dec. 26th, 1598, they performed for the Queen at White Hall, and had a date booked there on New Year’s Day. But they lacked a permanent home. This problem was solved during their short break between royal performances when the company, including Shakespeare, his fellow actors and a master builder, went to a disused building called, appropriately, The Theatre.

Bankside’s Globe Theater Photo by David Jensen

In the dead of a snowy night, the group took The Theatre apart, log by log. In spring, they moved the then dried-out timber to Southwark, having located vacant land in Bankside. Their structure emerged as The Globe. Ironically, the man who owned the land—but not the Theatre building—happened to be at his country estate that December night. Although he subsequently sued, he lost his case, since the building had been left to original owner James Burbage’s sons, both actor-members of The Lord Chamberlain’s Men. Also, not incidentally, Elizabethan actors carried real weapons for their stage fights, and many were skilled swordsmen who deterred the growing crowd of spectators drawn to the illicit activity. It was like a scene out of a play; definitely Shakespearean.

A Jester for the Ages. An actor recreates the energy and humor that drew thousands to the playhouses of Bankside in Elizabethan times. Photo courtesy of London Walks

Today, a stroll around Bankside offers visitors discoveries that include the reincarnated Globe Theater, which 400 years ago was home to The Lord Chamberlain’s Men. Next door, you’ll find the Tate Modern Art Gallery—a former power station—and the Oxo Tower. Splendid views across the Thames are highlighted by St Paul’s Cathedral, with its landmark 17th-century dome.

Heading into The Globe, we could almost be in Elizabethan times. The white plaster octagonal building with its thatched roof is a new, 1994 version of the original, the dream of American actor-director Sam Wanamaker. However, audiences still pay to stand among hundreds in the mosh pit (“like being at a rock festival,”) where they are close to the action on stage. In its heyday, Shakespeare’s company put on as many as thirty plays per season, and long runs were unheard of.

The Globe’s open roof means afternoon performances only. So, on a Saturday in Bankside you’ll find the place bursting with energy. High tea is served at The Swann, next to the theater, with choices of Vegetarian, Traditional and Romeo and Juliet–themed delicacies. On our tour we saw actors onstage busily rehearsing and were told to keep quiet and take no photos. The play must go on, even 400 years after it was scratched out with a quill pen. Among the gift shop’s items are cloth shopping bags (“Shakespeare’s My Bag”) and blood-spattered tea towels that read, Lady Macbeth style, “Out damned spot!” Others feature lines from A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Twelfth Night (“I was adored once too”). Tragedy, romance and comedy, all on a Bankside afternoon.

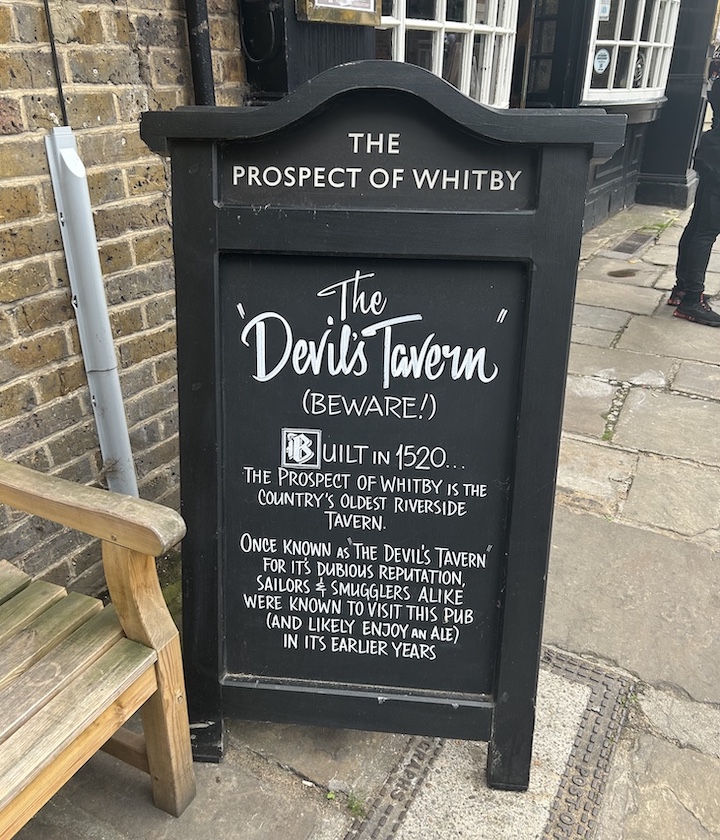

The sign outside The Prospect of Whitby, London’s oldest riverside pub, encapsulates its long and storied history. Inside the Ladies washroom, another sign cautions women whose internet dates have gone sour, to ask at the bar for “Angela” and help will arrive–signalling the continuity among the Devil’s Times and our own. Photo by Nancy Wigston

Far off the tourist trail in Wapping, you’ll find a 1520 riverside pub-restaurant called The Prospect of Whitby. A captain used to anchor his vessel of the same name in this spot, so the pub became known by the boat’s name. It’s very quiet on a summer Sunday, with families and dating couples enjoying drinks, Thames views, and generous plates of fish ‘n chips. The flagstone floor is original. On the sandy shores below, children play ball or give fishing a try. Hard to believe that Captain Kidd and other piratical types hatched their schemes here, or that writers like Samuel Pepys and Charles Dickens enjoyed respite from the city in this same spot. But things change. Today, Wapping is in the heart of the chic Docklands quarter, where flats sell for a million pounds. But this is London, where old and new coexist quite comfortably, like the enduring image of a famously independent queen, and neither monarchy nor beloved public houses are much inclined to change.![]()

Nancy Wigston has connections to England that stretch back to her grandfather, who left Cumbria for North Bay in Canada’s “Near North.” He lost neither his roots–wearing a bowler hat even when fishing–nor his accent. A year in Cambridge proved too damp and chilly for his granddaughter, who returned to Montreal and then moved to tropical Asia. Her daughter reversed the trend and is a professor at the University of York in Yorkshire, where Wigston is rediscovering England’s cultural and historical riches. Please see Wigston’s recent articles on York’s Roman and Viking history and the history of London’s World War II spies.