Hvar Town’s port illuminated at nightfall with berthed yachts and the hilltop citadel in the background. Credit: Hvar Town Tourist Board Archive

Our speed boat quietly chugged into a secluded cove off the Pakleni Islands archipelago where forested bluffs adorn a rocky coastline. The gentle water – aquamarine and clear – brought to mind a Caribbean dream. But that setting of sun-drenched islands is on the other side of the Atlantic. Instead, we had zipped across a small channel of the Adriatic Sea from Hvar Town, only a 10-minute ride to find yet another slice of a seemingly tropical paradise.

The difference? In May, Croatia’s brisk morning breezes are hardly tropical. Spring is actually a great time to visit Croatia’s Dalmatian islands, before the onslaught of summer heat and waves of tourists.

Hvar and Korčula, the touristic hot spots with their historic old towns; the less populated Brač and Mljet, known for their small villages and natural wonders; and the Pelješac Peninsula, connected to the mainland by a narrow sliver of the coast and known for some of Croatia’s best wines.

Hvar or Korčula?

Which of the two most popular islands to visit? Hvar, known for its upbeat pace, nightlife and summer crowds; or quiet and laid-back Korčula with a more rustic and small town feel. Both have excellent restaurants, historic medieval sites and much to do beyond the old towns.

Tranquil waters surround much of Korčula, which juts out as a peninsula with a rounded shoreline. The Dalmatian Coast’s brilliant sunshine illuminates the bright blue hues of the Adriatic Sea. Photo courtesy of Domagoj Miletic Photography, Visit Korčula

Each has dozens of beaches – sandy, pebbly and secluded coves. Vineyards and wineries offer tastings from grape brands found only on the islands. Beekeepers produce unique honey brands rooted from heather, lavender and sage flora. Olive groves dot the hillsides, sharing mountainous terrain with dense forests. Towns and villages with their clusters of rooftops add pops of earthen red tones to the green landscape.

Once I realized only an hour ferry ride separates the two, the decision was easy. I’ll visit both and I’m glad I did.

Korčula Town’s Venetian Legacy

Pleasure boats bob gently off Korčula Town’s palm tree-lined shore, where a young girl hawks seashells spread out on a blanket. “It’s our version of a lemonade stand,” jokes island tour guide Bojana Lozica. “I used to sell them when I was a kid,” she admits. “Korčula is still a very good place for raising a family. It’s very safe.”

There’s a grand stone stairwell leading up to the Old Town’s entrance, the 14th century Land Gate, also known as the Revelin Tower, capped with crenellated parapets. Some of the 13th century town walls remain, half as high as they once were, chiseled down to improve ventilation in a cramped fortress during medieval days.“We had a wooden draw bridge here in the past over a moat filled with seawater to stop intruders,” Lozica explains.

Revelers wear colorful sea-themed costumes during Korčula Town’s Half New Year’s Eve celebration in late June, with fireworks and parades. They crowd the grand stairwell leading up to the Old Town. Photo courtesy of Domagoj Miletic Photography, Visit Korčula

Today, many of the 15th through 17th century buildings house modern apartments and upscale restaurants serving seafood and Croatian specialties. Medieval planners strategically shaped Korčula Town with narrow alleyways branching off a central street. “East side streets are curved to slow down cold winter winds, while west side streets are straight allowing no restrictions for summer winds,” says Lozica.

The ancient Greeks first colonized the island in the 6th century BC, followed by the Romans. But it was the Venetians starting around the 12th century who left the architectural legacy we see today. St. Mark’s winged lion sculptures – the symbol of the Venetian Republic – remain on the town walls and in the Old Town’s loggia, its echoing acoustic qualities ideal for local concerts. The Bell Tower of St. Mark’s Cathedral stands tall above the eponymous square. Two Tintoretto paintings sit inside the Gothic-Renaissance cathedral, one at the main altar depicting St. Mark, the patron saint of Venice.

Marco Polo Slept Here?

Under Venetian rule came significant historical developments. One of Europe’s oldest books of law, the Statute of Korčula, was first drafted in 1214. Two of the old manuscripts remain today, one in a private collection on the island and the other in Venice. “It was a very important source of information for the rule of life and society on the island,” notes Lozica. “We’ve had that information preserved. Usually, it gets lost to history.”

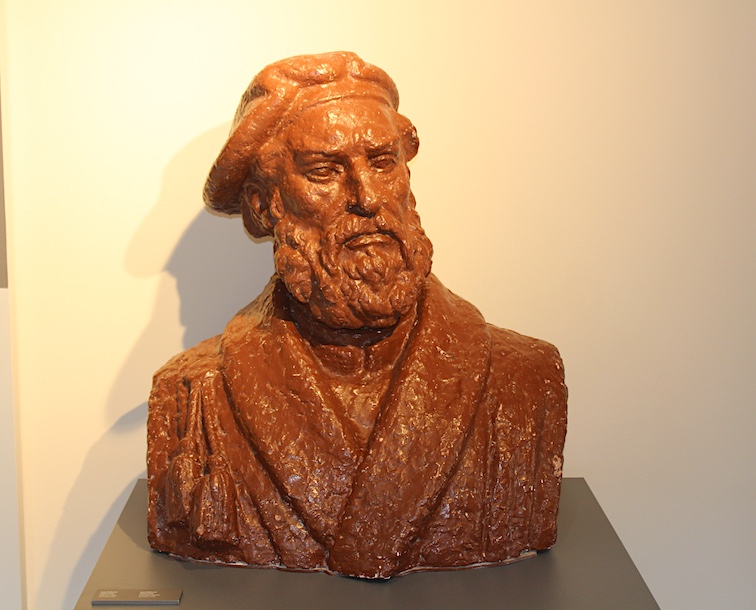

Bust of Marco Polo in the Marco Polo Museum in Korčula Town. Photo by Richard Varr

Furthermore, the locals proudly tout Old Town is the birthplace of 13th century explorer Marco Polo. “We cannot claim for sure he was born here, but we do know the house where we have the Marco Polo Museum was in ownership of the Polo family and they did spend part of their lives here,” says Lozica, explaining that back then the island was then under Venetian rule so the birthplace would be written as Venice.

“I like to call him our most famous local,” she asserts. “Venice claims Marco Polo is theirs, but we don’t give an inch.”

A Flavorful Island Tour

A drive across 29-mile-long Korčula reveals a landscape of dense oak and pine forests close to gardens growing potatoes, cabbage and peaches. Vineyards thrive in valleys and on hilltops overlooking the sea, growing indigenous grape varieties producing the island’s own popular wine brands including Pošip, Rukatac and Grk.

At the Black Island Winery in the central island village of Smokvica, a server pours 2023 Rukatac, a light dry white with a crisp finish. In contrast, tasting white Pošip from the same year reflects a more golden color with a richer flavor and lingering taste.

“Pošip is from an indigenous variety of grapes that was discovered here in Smokvica 150 years ago by accident,” says Milijana Borojević, Director of the Korčula Tourist Board. “A local farmer was working his vineyard when he spotted the grape. He tasted it and liked it, so he took it home and started growing it in his own vineyard.”

Many would argue liqueur-like Grk from the Lumbarda region, just a few miles south of Korčula Town, is the island’s most popular wine. The three-letter name’s origin relates directly to those who first settled the area, or another theory that Grk translated from Croatian means bitter or tart. “The wine has been around maybe a couple thousand years, apparently back to when the Greeks inhabited the island,” says Borojević. Grk is noted as a dry white often with fruity and pine notes, and with a mineral content from the area’s limestone soil.

Olive groves deluge the island’s west side where the town of Blato is key to Croatia’s olive oil production. But on this trip, we instead taste Lumblija, a local sweetbread made with thick red grape syrup mixed in with walnuts, cinnamon, cloves and other spices. Traditionally baked to celebrate All Saints’ Day (Blato has its 14th century Parish Church of All Saints on the main square), the dark brown, thick textured cake is now made year-round. Noted as one of Korčula’s most significant gastronomical achievements, it has earned a European Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) label ensuring the authentic sweetbread comes only from Korčula.

Outside the port town of Vela Luka on Korčula, an archeological dig continues in the Vela Spila cave first inhabited 18,000 years ago. Photo by Richard Varr

Other island highlights include that Blato has the second longest linden tree alley in Europe other than Berlin. The western port town of Vela Luka is vying for a spot in the Guinness World Records for having the longest stretch of contemporary sidewalk mosaics. Outside the town, an archeological dig continues in the Vela Spila cave first inhabited 18,000 years ago, from where a walk along a path of rosemary plants leads to a scenic viewpoint of Vela Luka and its adjacent harbor. And almost every village has a dance company to celebrate the traditional Moreska and Kumpanija sword dances stemming from a historic battle.

Actors participating in the popular Korčula tradition of sword dancing. The Kupanija dance is based on a time when local island men would form a village guard militia to defend against invaders. Photo courtesy of Domagoj Miletic Photography, Visit Korčula

Back in Korčula Town, a string of casual and upscale eateries line the eastern waterfront along a leafy promenade with views of the mountainous Pelješac Peninsula. In the town center, Adio Mare, noted as one of Korčula’s best restaurants for seafood, is housed in a former shipbuilding workshop and has rooftop seating. Dishes include charcoal-grilled white fish and squid, washed down with Grk and Pošip wines.

Hvar Town – Meet Me in the Square

After stepping off the ferry from Korčula, it’s only a short walk to Hvar Town’s St. Stephen’s Square. The square is a meeting point where new arrivals decide their course of action while summer day trippers who have moored their luxury yachts along the harbor select a local excursion boat for the day.

“Let’s meet in the main square” is often overheard as tourists and locals alike gather to visit restaurants and shops in the heart of Hvar’s St. Stephen’s Square. Photo courtesy of Hvar Town Tourist Board Archive

“We say our main square is our dining room,” says Hvar tour guide Loridana Knežević. “Especially on Sundays after church, as everyone goes for coffee here. This is where our children play. They ride bicycles and even play football here.” Edged with mostly shops and restaurants, the square’s focal point is the Renaissance-era Cathedral with its 17th century bell tower and a Venetian School artist’s painting of St. Stephen, the island’s patron saint, behind the high altar.

Knežević explains how the Ottomans destroyed the town in 1571. “The church you see today was rebuilt later. They were attacking us constantly and every time they touched ground here, they took women as slaves and grain for food,” she says. “Try to imagine the atmosphere. Turkish raids, a plague and an explosion of gunpowder within ten years,” she continues, the latter referring to the 16th century Citadel on a hill above the square with its sweeping views of the harbor and Pakleni Islands.

The Arsenal on the square’s waterfront, once a former dry dock for Venetian war ships, is now an event venue. It includes Hvar Town’s historic theater, opened in 1612 to quell a disagreement between noblemen and fishermen. “In those centuries we lived on the export of salted fish,” explains Knežević. “Thus, the fishermen wanted to take part in all decisions made in Hvar.” Venice sent a new governor to solve the problem, proposing to bring both groups into the same room.

A waterside view of Hvar Town with the Citadel fortress perched above. Photo by Richard Varr

At the Franciscan Monastery just south of the port, sweet-sounding harmonies echo through a small chapel not far from the dining hall with a wall-wide painting of the Last Supper. While the artist is not known for sure, legend has it that a sailor sickened with plague jumped off his ship and swam to shore. “No one wanted a sick foreigner, but the Franciscans opened their doors and gave him shelter,” says Knežević. “He survived and to show his gratitude, he painted the Last Supper.”

Hvar’s UNESCO Recognized Agave Lace

From the square, pedestrian streets ascend the steep hillside and include restaurants and apartments, although to get there one must often traverse many steps and arduous inclines. One street leads to the Benedictine Convent founded in 1664, where a handful of nuns continue their tradition of lace-making through the centuries, weaving circular and geometric-like designs with threads pulled from agave leaves. The lace is a UNESCO recognized cultural heritage produced only in a few Croatian locations.

The convent’s lace-making origins using agave are unknown. “They probably just used what they had,” says Knežević. “I would say it was a combination of an aha moment and creativity.” Their thin-crafted lacework – every piece different – hangs in the convent’s museum. The nuns offer others for sale, many costing hundreds of Euros.

Restaurants, many of them ascending the hillside that leads up to the Citadel, line the narrow streets of Hvar Town. Photo courtesy of the Hvar Town Tourist Board

Come dinnertime, it can be overwhelming to choose from Hvar Town’s wide-ranging restaurants, some side-by-side in the main square. A few blocks up the hillside is Grande Luna, its upper floor dining room with an open rooftop. Instead of the grilled Adriatic squid or spiny lobster on the menu, I opted for traditional Gregada, a whitefish stew.

“If you want to try something domestic, this is it, a very old recipe in Hvar Town,” explains hostess Katijana Bilandžić whose father is the chef of this family-owned restaurant. “Back in the day when fishermen were catching fish regularly, the wives were cooking this very simple tasty dish, boiling the fish with potatoes, olive oil and onions. And if you have a domestic olive oil, it’s even better.” Other traditional dishes on the menu include pastičada which is slow-cooked beef with vegetables and red wine served with gnocchi or potatoes, and salty black risotto with cuttlefish.

Hvar Island Tour: Lavender and Croatia’s Oldest Town

Purple fields of lavender flowers dot the hillsides and valleys of this 42-mile-long island from June through early August. “From 1900 to the 1950s, we were producing about 10 percent of the world’s lavender,” explains Hvar tour guide and driver Aleksandar Balažinec. That’s no longer the case as tourism has taken over much of the island’s economy, with lavender today sold mostly as scented samples of flower petals and little bottles of lavender oil.

A tasting table with samples of olive oil and honey at Mikletovi in the Hvar village of Brusje. Photo by Richard Varr

“These days, it’s all about wine and olives,” continues Balažinec, much of it grown on the island’s abundant terraced fields. A technique used since the early Greek settlements, the walls help retain soil and minimize erosion, particularly along slanting terrain.

The hilltop village of Brusje is known for its beehive tradition, something a bit different from the numerous wine and olive oil outlets. At the small family-owned business Mikletovi, we sample honey from strawberry trees, rosemary bushes and heather plants, typical from the area flora, with textures varying from thick solid to viscous, all with subtle differences in sweetness. Also unique to this tasting experience, local brandies made with herbal, blueberry and honey flavors.

It’s only a 20 minute drive from Hvar Town to reach the oldest Croatian town and one of the oldest in Europe, waterside Stari Grad (translated means old town), a UNESCO World Heritage Site. First settled around 3500 BC, Greeks arriving in 384 BC named it Pharos and took advantage of the fertile plain east of town known as Hora or Ager, cultivating wine grapes, olives and other crops.

Stari Grad on the island of Hvar is the oldest town in Croatia and one of the oldest in Europe. As a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site, chances are good the community will be preserved. Photo by Richard Varr

Today, restaurants and shops line the tranquil waterfront harbor where small pleasure craft moor. “In the high season, it’s totally opposite from Hvar Town which is often filled with young kids,” says Balažinec. “I tell guests it will be like you’re in another country.”

A key historic highlight is the home and grounds of 16th century poet and nobleman Petar Hektorović who wrote about the lives of local fishermen. “As a poet, he was one of the fathers of Croatian literature and wrote one of the first poems in our language,” says palace guide Niko Politeo. “It’s not easy to read the Croatian language from 500 years ago, but it’s still a must read.”

Trogir: A Medieval Island Town

The palm tree-lined promenade along Trogir’s harbor allows visitors to stroll between the Kamerlengo Castle at the island’s edge and the 17th-century St. Lawrence Cathedral. Photo by Richard Varr

This tiny island packs a lot of history. “Trogir has been continuously inhabited for 4,000 years,” says town guide Antea Kovačević. Separated by a 100-foot pedestrian bridge from the mainland, the UNESCO World Heritage Site and hot spot for day trippers is a half hour drive from Split.

When the Greeks first founded the ancient colony then called Tragurium, it was actually part of the mainland. With Roman rule during the 1st century BC, it’s believed their engineers dug the narrow canal creating the island. While only remnants of the Roman period remain including repurposed columns and mosaics, much of the architecture we see today – palaces, churches and a castle fortress – came with Venetian influence starting in the 13th century.

One of Trogir’s most striking highlights is the Romanesque sculptures adorning the portal of the Cathedral of St. Lawrence, finished in 1240 by Master Radovan and his pupils. The multi-tiered artwork features lion figures supporting Adam and Eve statues, and small carvings of biblical scenes of the life of Christ including the Nativity, Three Kings and Adoration of the Shepherds.

Trogir’s three-story Town Hall, decorated with coats of arms, is located on the main square opposite the 14th-century loggia and adjacent clock tower. Photo by Richard Varr

The three-story Town Hall decorated with coats of arms fronts the main square opposite the 14th century loggia and adjacent clock tower. The Museum of Sacred Art has 14th and 15th Venetian artist masterpieces by Gentile Bellini and Paulo Veneziano. The small Romanesque 13th century Church of St. John the Baptist is a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Most day trippers visiting Trogir enjoy crowding the restaurants and gift shops along narrow medieval streets. They stroll the waterside promenade with visiting yachts that leads to the fortress-like Kamerlengo Castle now used as a theater and concert venue. “Trogir is only one kilometer all around when walking – so simple because everything is in one place,” says Kovačević.![]()

Richard Varr is a former newspaper and television reporter who lives in Houston, Texas. His previous stories for EWNS examined coffee brewing in Bogota and Spain’s old Roman town of Mérida.