Why do we love elephants? Maybe it’s because these largest of all land mammals are both immense and endearing. The majestic, flappy-eared creatures have brains three times bigger than that of humans; they are one of the few species that can recognize themselves in a mirror. They are well known for communicating over long distances, sharing child rearing and grieving their dead. Baby elephants suck their trunks much like human infants suck their thumbs. And is there anything cuter than a small elephant, trotting along after its mother and aunts?

Elephants have been revered – the elephant god, Ganesh, is the most widely worshipped deity in the Hindu pantheon. In Buddhism, the elephant is seen as embodying the trait of luminosity, a clear state of mind.

So why has the elephant population of Africa decreased by 40% in the past ten years and 90% in the past century, according to the World Wildlife Fund? For the endangered African elephant, the answer is poaching – killing elephants for their ivory tusks. Automatic weapons make it easier than ever before. But in this time of synthetic materials, used in everything from piano keys to jewelry plus bans on ivory, why is selling illegal ivory still such a big business?

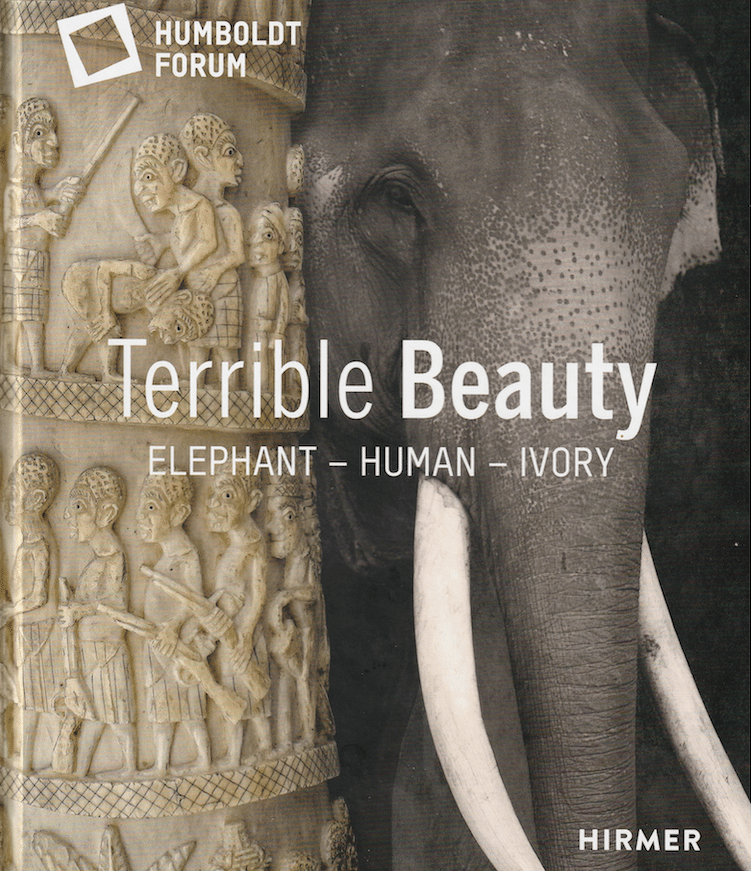

The book, Terrible Beauty: Elephant – Human – Ivory explores these questions. It describes the passion for ivory from ancient times to the present. And it looks at the elephant as an ecologically important and endangered species.

Terrible Beauty was published in July 2021 to accompany an exhibition that marked the opening of the Humboldt Forum, a new museum of non-European art on Berlin’s Museum Island, in the historical center of Berlin. The exhibit includes items from Berlin State Museums, the Natural History Museum and the National Museums of Kenya.

The coffee table book is a collection of articles from archeologists, art historians, biologists and others. It is illustrated with photos of elephants and of ivory artifacts, from weapons to musical instruments, from statues to jewelry. It explores the issues of colonialism, displays of ivory in museums and the destruction of natural habitats. The exhibit directors call these issues “the elephant in the room.”

African and Asian Elephants

Elephants live in both Asia and in Africa. Asian elephants, numbering from 45,600 to 49,000, are threatened not so much by poaching but by shrinking habitats due to deforestation and population increases. The country of Laos once called itself Lane Xang, the “Land of the Million Elephants.” Today elephants in Laos number 850, with only 400 in the wild.

African elephants, the main victims of poaching, number around 420,000 today. They are found in 37 countries over a range of several million kilometers. What’s the difference? Asian elephants have a hump and are smaller than their African cousins. They also have smaller ears. Only Asian elephant males have tusks, while both male and female African elephants have them.

In a chapter called “The African Elephant, Importance and Endangerment,” German biologist, Katharina Trump, describes elephant tusks as ivory protrusions formed from two of the elephant’s upper incisors. “Elephant ivory, traded at high prices, is thus nothing other than a normal, though greatly overgrown, tooth,” she writes. It is the hunting of these “teeth”, a tiny part of a huge animal, that accounts for the 90% decrease in elephant populations in the last century. For according to World Wildlife Fund estimates, in 1930 there were some ten million elephants roaming the African continent.

Elephants in the Serengeti Photo by B Ikiwaner

Tusks grow throughout the animal’s lifetime and can be large and heavy. Once gone, they don’t grow back. Elephants use tusks in their search for food, in digging for water and in self-defense

Elephants have an immense impact on their environment. They are nature’s landscape gardeners, writes the author. “Their grazing keeps the vast grasslands of African savannahs open, preventing unhindered growth of shrubs and trees,” she explains. Elephants are also seed planters – through their digestive system they transport and excrete seeds over distances up to 65 km.

Elephants can live without tusks. But no elephant can live without its trunk, an elongation of the nose and upper lip. “With roughly 40,000 muscles, the elephant’s trunk is considerably more richly furnished than the entire human body.” writes Trump. The trunk is involved in social behavior – encircling the trunk and tusks of a fellow elephant as a greeting. Or a mother reassuring her calf by grazing its back with her trunk.

Bans

It has only been in the last 50 years that concern over disappearing elephants has led to bans. In1980 CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, issued a ban on the trade of ivory from African countries. Asian elephants have been officially protected since1975.

The international community banned the ivory trade in 1989, and for a while, it worked. But National Geographic notes that since 2007, large-scale poaching has resumed, and the elephant population has fallen as low as 419,000.”

Poaching

Bans can stop legal sales, but they don’t always impact illegal trade. Ivory poaching has become a branch of organized crime. China’s ban in 2017 did cause a drop in the sale of ivory tusks. Ivory products are still sold in some Chinese stores. And Chinese shoppers can easily find ivory products for sale in Southeast Asia – Vietnam, Laos and Thailand. They are not stopped by Chinese customs officials.

Poaching remains a big business – ivory is called “white gold”, worth billions of dollars. Yet elephants are worth 76 times more alive than dead, writes photographer and artist, Asher Jay, in a chapter called The Half Remembered Past. Referring to data from Scientific American, she explains that “Ivory from a poached elephant sells on the illegal market for about $21,0000. A living elephant, on the other hand, is worth more than $1.6 million in ecotourism opportunities.”

Elephants on Parade

I remember going on an “elephant safari” in Botswana, a sparsely populated Southern African country known for its large elephant population. At 6 am we piled in a jeep for the early morning drive. Around us was lion-colored savannah punctuated with green acacia trees.

Suddenly, an elephant nonchalantly crossed in front of our jeep. It seemed like an apparition, especially because these heavy animals walk silently, as if the sound is turned off. Then, more elephants appeared – females with their little ones. Later that day we saw males imperiously surveying the herd. (Outside of procreation, calves and bulls live separate lives). The adolescent males, our guide told us, were trying to show off and impress the big guy.

Not all countries have the infrastructure for these elephant sightings, writes Burmese veterinarian, Khyne U Mar in a chapter called “Voices of Ivory.” She established an elephant research center in Burma and is a guest lecturer at the Royal Veterinary College of London.

Many wildlife experiences are based on entertainment, she explains. “They use elephants, ride them, and make them do tricks. This is not ‘wildlife tourism’, this is an abuse of the animals.”

Towers of Ivory

For centuries, ivory has been used for everything from jewelry to piano keys, from combs to fertility objects. As early as 40,000 years ago, mammoth tusks were used to carve figurines. Indeed, ivory carving is one of the oldest arts in Asia.

In the ancient world, elephants roamed not only Africa and Asia but parts of the Middle East and the Sahara. Ivory was used for decorative objects and tools, just as in the centuries that followed. But in a striking echo of the current threat, in the 4th century BC, the North African elephant went extinct. The reasons were “overhunting and climate change,” writes Sarah M. Guerin, Assistant Professor of Medieval Art at the University of Pennsylvania, in a chapter called “Material of Might.”

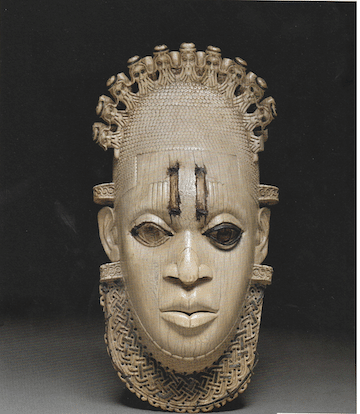

In the book’s opening chapter, “Ivory and Its Elephants,” art historian and Humboldt Forum General Director, Hartmut Dorgeroh, and Laura Goldenbaum, an academic consultant at the Humboldt Forum, write that in no other material is the “grandeur and power of a living creature reflected in the lifeless object…” No other material, they add, has stimulated such artistic virtuosity.

Why? Awe and fear of these strange, powerful creatures make ivory stand for “concentrated energy”. At the same time, its milky color and subtle markings make it ideal for depicting the human body.

Sixteenth Century ivory carving of a Benin woman, carved in Edo (modern day Japan) now located in the British Museum, London.

Ivory and the Human Body

In a chapter called “Encounters with Ivory, Body Image, Body Contact, Body Replacement”, art historian Alberto Saviello, part of the curatorial team that put together the Berlin exhibit, notes that poets of various epochs have compared the body of the beloved or specific parts to ivory. In the Old Testament Song of Songs, the woman’s neck is likened to a tower of ivory. There are many other examples of parts of the body – cheeks, forehead, breasts – likened to ivory in both Persian, Arabic and European Baroque poetry, explains Saviello. It’s not surprising, he notes, that “In almost all epochs and regions of the world…ivory has been a favored material in which to create figures with a distinctly erotic or sexual expressiveness.”

In the story of Pygmalion, in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the King of Cyprus, afraid of real women, carved his ideal woman from ivory, only to fall in love with it.

Ivory was used to make artificial teeth in antiquity. It was even used as a bone replacement. From 1890 on, Saviello notes, surgeons used ivory as joint implants. If conditions were sterile, the implants were successful. In the 1960’s a Burmese surgeon replaced hip joints with ivory prostheses.

The Elephant in the Museum

Western museums of full of ivory works of art, “exported” from Africa, particularly during times of colonization. It is estimated that over 30,000 tons of ivory were shipped to the UK alone from Africa in the 18th and 19th centuries. This translates to at least half a million elephants.

In a chapter called “Living Material: Human Supremacy in Ivory Exhibitions,” Stephanie Marek Muller points to the exploitation of both humans and animals in the colonial domination of African countries. Should museums not display ivory? According to Burmese veterinarian Khyne U Mar, museums should show works made of ivory. However, they should make it clear that the works in question “are ancient and that the ivory came from elephant populations that at the time thrived and were not endangered.”

African museums are coming up with their own innovative ways of displaying their artifacts and educating their viewers. In the chapter, “Facing the Challenge of Ivory in Museums, The National Museums of Kenya,” author Lydia Ktungulu, Senior Exhibitions Designer at the National Museums of Kenya, writes about how the museum uses ivory to educate viewers about the country’s huge ivory collection, dating back from prehistoric fossilized ivory.

At the same time, the museum educates viewers on the current threat to elephants. She notes that the illegal ivory traders, faced with a dwindling supply of elephants, are now robbing museum collections. As a result, a major attraction, a model elephant named Ahmed, complete with tusks, is given 24-hour security.

Two elephants near water in Chobe National Park, Botswana. Water used for drinking and bathing draws elephants. Photo by Jacqueline Swartz

Elephants at the Movies

Other chapters in the book touch on some unexpected topics. One, called The Elephant as Film Star,” describes elephants in films such as the 1951 The African Queen, with Humphrey Bogart and Katherine Hepburn, and the 1962 Hatari.

Another chapter shows short answers to questions posed by children in a school near the Berlin Humboldt museum. Hopefully, they will grow up with an appreciation of elephants and the urgent need to protect them from extinction. For as more than one author notes, poaching will stop only when there’s no demand for ivory. Either that or when there are no more elephants..![]()

East-West News Service contributor Jacqueline Swartz lives in Toronto. She has profiled Athens, Montreal and Baden Baden.