Phnom Penh’s skyline is mostly a mix of the old and the new. Often left unseen are slowly decaying French colonial buildings that Khmer preservationists are rapidly working to save. The colonial neighborhoods, not Chinese-built skyscrapers, are the main drivers of tourism. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

By John Gottberg Anderson

From the steps of the Poste Cambodia building, the colonial history of French Indochina comes alive at a single glance.

Plâce de la Poste, to use the French vernacular, was a place of pride for citizens who had been transplanted from their European homeland to the hot, humid tropics in the 19th century. Dominated by the 1895 post office, it was the heart and soul of Phnom Penh’s original French Quarter, framed on the west by the hilltop pagoda of Wat Phnom and on the east by the embankment of the flood-prone Tonlé Sap river.

Long after an original garden was replaced by open parking, the surrounding collective continues to exude a sense of cohesive community. Known today as Post Office Square (despite its triangular shape), this urban hub is enclosed by a cluster of edifices from a bygone era. They are now government offices, restaurants and cigar bars in various stages of restoration. One can easily imagine stylish French women and dapper men scuttling between bistros and boulangeries, their umbrellas shading them from the sultry sun as they walk.

Around the corner of Quay de Verneville (Street 106), the stately buildings of the old financial district — the Treasury and the Securities building, as well as the modern SOSORO currency museum in the former National Bank of Cambodia — persist. Only slightly further is the grand Raffles Le Royal Hotel, now nearly a century old.

This is the Phnom Penh that most visitors don’t see. Popular tours may bring them to the trappings of royalty and to the devastation of the Khmer Rouge era. Still, it is only here, amid the structures of the mid-colonial era, that one can find the ambience and flavor of a historic city once called “the Pearl of Asia.”

Cambodia Post, built in 1895 by architect Daniel Fabré, rises above Place de la Poste at the heart of Phnom Penh’s original French Quarter. It was framed on the west by the hilltop pagoda of Wat Phnom and on the east by the embankment of the flood-prone Tonlé Sap river. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

From the beginning

Although Phnom Penh dates its origin from the 14th century, it wasn’t until 1863 that the city began to take its modern form. That was when Cambodia became a French protectorate, following King Norodom’s request for assistance in deflecting the armies of Thailand and Vietnam. In 1866, Norodom moved his capital from rural Oudong to the village of Krong Chaktomuk, at the confluence of the Mekong, Tonlé Sap and Bassac rivers. Four years later, he built a Royal Palace in the iconic style of the Khmer Empire. Its spires still soar skyward, its sacred elements reflecting Hindu and Buddhist mythology.

The Khmer population was drawn to the area near the palace and Wat Ounalom (1443), the Buddhist nation’s spiritual center. Chinese merchants and traders settled immediately north, where their multi-story riverside shophouses first appeared. French bureaucrats and residents were located north of the market district but south of land grants accorded to the Roman Catholic church.

Multi-story shophouses built by Chinese merchants and traders between the 1890s and 1960s still dominate many urban streets throughout Phnom Penh. They are among the colonial-era buildings that have been particularly targeted for demolition. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

Beginning in 1889, visionary administrator Huyn de Vernéville executed a plan to drain the marshes west of the rivers and build new roads, bridges and docks along Sisowath Quay. After a series of devastating fires, the largest in 1894, he called for brick and cement to replace wood and bamboo as building materials. Ancient Wat Phnom (1372) was refurbished as an urban landmark and surrounded with parkland. Norodom Boulevard was broadened as a link between the European and Cambodian districts, and numerous grand villas sprang up in those environs.

No structure in Phnom Penh is older than Wat Phnom, originally constructed in 1372. In the late 19th century, when it was refurbished as an urban landmark, it was surrounded by parkland, including a great clock and classical Khmer statuary. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

The post office and adjacent Central Police Commissariat (1892) are among more than 500 colonial-era structures (mostly residential buildings) that survive today. Among them are “Colonial Traditional” buildings such as the National Museum (1920) and the domed Art Deco “Central Market” (1937).

After French bureaucrats departed in the 1950s, the New Khmer architectural movement burgeoned. Led by architect Vann Molyvann, its legacy includes the Independence Monument (1958), commemorating the nation’s freedom, and the Chaktomuk Conference Hall (1961).

Now a popular wine bar and restaurant, Le Manolis was built as a hotel in 1891. It was the home of André Malraux, a celebrated novelist and the first Minister of Culture of France, in the 1920s. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

Post Office Square

Few organized tours in contemporary Phnom Penh consider the colonial architectural heritage. This is a shame. It can easily be explored in a stroll of only about 10 minutes from Wat Phnom, the medieval pagoda that is, in its essence, the center of the city. Poste Cambodia and its prominent clock dominate the broad square where Street 19 merges with Street 102. Built by architect Daniel Fabré, it has been reconstructed several times, most recently in 2004. Roman arch windows and Corinthian columns surround the ground floor. Balconies with balustrades and sculpted pediments adorn the second story.

Across Street 100 is the elaborate but vacant Police Commissariat, its elegant façade and colonial charm reflecting the blend of European and Khmer influences. Throughout this neighborhood, one sees various European architecture styles from the end of the 19th Century, inspired by Greek, Roman and Italian Renaissance palaces.

The Banque d’Indochine now houses the Palais de la Poste French restaurant and the French Development Agency, which is responsible for Paris-backed infrastructure development in the country. Built in 1890 and now undergoing a major restoration, the building expresses its grandeur with porte-cocheres and ornate designs. Opposite, the Hotel Manolis (1891) is a popular wine bar and restaurant known as the home of André Malraux, a celebrated novelist and the first minister of culture of France, in the 1920s.

Hotel Le Royal

At the Hotel Le Royal, which opened in 1929, architect Ernest Hébrard blended French Colonial styles with local influences. During the mid-1950s, to facilitate international tourism, the hotel added rooms on the upper floors of the main building, plus 30 bungalows, an outdoor restaurant, a swimming pool and a terrace. But tourism ended abruptly with the Khmer Rouge in 1975, as the regime forced everyone affiliated with the building to leave.

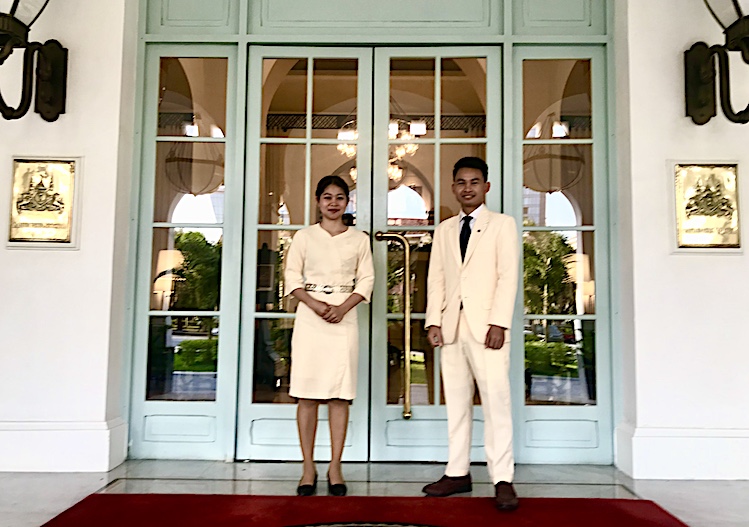

Front-door attendants greet arrivals to Raffles Hotel Le Royal, a colonial-era treasure since it opened in 1929. Today it retains architect Ernest Hebrard’s grand wooden staircase and its glazed light-well over the central entrance foyer. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

Five years later, the hotel reopened as the Hotel Samakki. In 1996, Raffles International Limited replaced the bungalows with three wings but left the original guestroom layout, the grand wooden staircase and the glazed light-well over the central entrance foyer. Today, the Raffles Hotel Le Royal features 170 rooms and suites, gracious service and impeccable attention to detail.

Nearby, the simple yet dignified National Library of Cambodia (1924) offers another salute to the past. Through the columned Grecian portico, above which the French word “Bibliothèque” is inscribed, somnolent ceiling fans ventilate a single large room with stacks of periodicals and rows of reading desks. A good portion of the reading materials is two decades out of date. UNESCO reported: “The Khmer Rouge threw out and burned most of the books and all bibliographical records; less than 20 percent of the collection survived.”

Bartenders at the Raffles Le Royal put on a show in the hotel’s famous Elephant Bar, renowned for one of Asia’s largest selections of gin. American First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, in 1967, was said to have introduced a cocktail called the Femme Fatale, made with champagne and cognac, and still on the menu. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

The Royal Railway Station is a memorable Art Deco building with two tall, square towers, built in 1932. Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot once used the station as his meeting hall. Reopened in 2010 after a long closure, it now accommodates limited service between Phnom Penh and Sihanoukville to the south and Poipet to the northwest.

It’s a short walk from Le Royal and its neighbors to the Central Market, “Phsar Thmei” in Khmer. The city’s biggest bazaar sits beneath one of Asia’s largest domes, 148 feet in diameter and 85 feet high. Architecturally, it doesn’t fit with the rest of central Phnom Penh: Its huge yellow dome and four spiderlike “legs” could have been downloaded from Transformers. But inside, Phsar Thmei is cool, spacious and filled with natural light, its stalls selling everything from gold jewelry to souvenir T-shirts, phone chargers to Buddha images, fresh produce to colorful flowers. Built upon drained swampland in 1937, it was renovated in 2011 by the French Development Agency.

The National Library of Cambodia, built in 1924, is a simple one-story building framed by a Grecian portico. It was ransacked in the late 1970s by the Khmer Rouge, who destroyed 80 percent of the collection, according to UNESCO records. Photo by Jogn Gottberg Anderson

The Palace neighborhood

Norodom’s Royal Palace of Cambodia (1870) remains the standard for classical Khmer architecture. Still the official royal residence, it encompasses 43 acres and includes the Throne Hall, Moonlight Pavilion, Khemarin Palace (home of King Sihamoni) and Silver Pagoda. The Napoleon Pavilion, a cast-iron prefab presented as a gift by Napoleon III in 1875, is architecturally out of place but nevertheless an intriguing addition.

The Napoleon III pavilion is architecturally out of place on the Royal Palace grounds, but remains an intriguing addition. It was a cast-iron prefab gift from French emperor Napoleon III in 1875. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

Adjacent to the palace, facing the rarely visited Royal Palace Park, is the National Museum of Cambodia. Its collection of Khmer art, over 14,000 artifacts from prehistoric to post-Angkorian, is the largest in the world, although only a small part may be exhibited at any one time. Architect George Groslier designed the building in 1920 in the tradition of Angkor. Three tall spires rise above the long roof and a central courtyard.

The Royal University of Fine Arts was the first university in Cambodia, founded by the French in 1917 as École des Arts Cambodians. The earliest students learned traditional drawing, sculptural modelling, bronze casting, silversmithing, furniture making and weaving.

The colorful UNESCO building was built prior to World War I as the French Baroque-style home of a wealthy Cambodian merchant. It has been home to the international organization’s Phnom Penh headquarters since 1991. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

Built prior to World War I as the French Baroque-style home of a wealthy Cambodian merchant, the colorful UNESCO building has been the organization’s Phnom Penh headquarters since 1991. Located catty-corner from the Moonlight Pavilion, the lavish structure previously (after the fall of the Khmer Rouge) had housed the Department of Conservation.

Devastation and reconstruction

Phnom Penh was carving an identity as a metropolis with a promising future until Pol Pot ushered in the age of Khmer Rouge terrorism in 1975. During fewer than four years ending in January 1979, the city (indeed, all of Cambodia) suffered irreversible damage. But with a more stable government since the 1990s, and with investment from wealthier Asian and European nations, urban development is again booming.

Wat Ounalom, considered the spiritual center of Theravada Buddhism in Cambodia, has been a fixture in Phnom Penh since 1443. Three of its heritage buildings from the 1930s were razed in 2022, sounding an alert for historic preservationists in the nation’s capital. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

Unfortunately, this has caused an inclination to replace older buildings with newer structures. Chinese shophouses are particularly targeted for demolition, but some dilapidated colonial-era buildings are also on the danger list. An alarm was sounded in 2022 when three 1930s heritage buildings at Wat Ounalom were torn down. In January 2023, Cambodia’s Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts announced a National Heritage database of buildings over 50 years old. In the ensuing two years, increasing attention has been directed to preserving and restoring historical sites, including the most famous “Killing Fields” locations, Choeung Ek and Tuol Sleng.

“We must continue to focus on protecting heritage buildings,” said Prime Minister Hun Sen.. Although he stepped down as prime minister in August 2023 after 38 years (to be succeeded by his son, Hun Manet), he remains president of the Cambodian senate.

Today’s modern skyscrapers showcase the creativity of young builders, including Cambodians trained overseas (especially in France and Singapore) and deep-pocket investors from China. One of the first big contemporary projects was the 617-foot Vattanac Capital Tower (2014), which includes offices and, on its upper floors, the luxurious Rosewood Phnom Penh Hotel, which includes the city’s best-known sky bar for sunset viewing.

Into the future

But even that has been eclipsed. Currently under construction are side-by-side high-rises soaring 133 floors to 1,968 feet. The old Hotel Cambodiana, with a history as turbulent as its political times, is proposed to be replaced by a 1,837-foot Skyscraper City complex. And more are in the works, including a lofty new Chinese-owned business park on Koh Pich (Diamond Island) at the confluence of the Mekong and Bassac rivers, just south of the urban center.

When it was announced in 2014, the Sleuk Rith Institute of Genocidal Studies was unveiled as a creative masterpiece. Iraqi-born architect Zaha Hadid’s splendid showcase will be an interlocked, five-building masterwork in the heart of the city. Unfortunately, it lacks international funding and has moved forward slowly.

For now, though, the city lacks an architectural philosophy in its urban zoning. It has a plan — but, as the World Bank notes, “The city’s ambitious Master Plan 2035 lays out a strategic vision for growth, but lacks a corresponding detailed land use plan and accompanying regulatory framework to support implementation. At the same time, an influx of foreign investment has contributed to fragmented urban growth, which puts additional strain on the city’s infrastructure.”

According to Chum Vuthy, director of the Phnom Penh Department of Culture and Fine Arts, a lack of budget and legal documentation makes the preservation of French-era heritage buildings difficult. Indeed, despite its rapid growth, Phnom Penh has no master plan to regulate land use and control development. The future of the city is in the hands of the private sector, which is growing according to immediate profits instead of future considerations.

Historic hotels

Ho Vandy, an adviser to the Cambodia Association of Travel Agents, is a champion of historic preservation. He argues that French colonial-era buildings play an important role in attracting those “cultural tourists” who prefer lodging in hostelries with a particular ambience, where they learn about the art, architecture, cultural traditions and lifestyles of the Cambodian people.

Besides the Raffles Le Royal, Phnom Penh certainly has no shortage of hotels that meet this criterion. Several of them occupy restored villas along Norodom Boulevard north of the Independence Monument. The Pavilion Hotel, for instance, was once the private residence of Queen Consort Sisowath Kossamak, mother of the late King Norodom Sihanouk. Built beside Wat Botun in the 1920s, surrounded by a spectacular walled garden, it reopened in 2006 after a long renovation, and now has 36 units in four period French Khmer-style buildings.

The White Mansion is one of several French colonial-era boutique hotels that serve visitors to Cambodia’s capital. During the 1990s, it served as the United States Embassy in Phnom Penh. Photo by John Gottberg Anderson

There are more of the boutique variety. The White Mansion once served as home to the US Embassy. The Governor’s House, on Mao Zedong Boulevard, also has seen its share of dignitaries. The Plantation Urban Resort was a former Bank d’Indochine building.

Then there’s the Renaksé Hotel, wedged between the Royal Palace and the Tonlé Sap. Shuttered since 2009, it has recently been showing new life, with construction crews performing a major renovation inside its high walls. Built in the 1890s, later home to the colonial Council of Ministers and to independent Cambodia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, it had fallen into disrepair by the late 1980s when it was taken from foreign Cambodian owners and left to deteriorate. Though battered and bruised, like the nation itself, it’s getting a new chance to survive thanks to preservation efforts.![]()

John Gottberg Anderson has covered Southeast Asia for the East-West News Service since 2019. He is a widely published American travel journalist and educator, a former Los Angeles Times news editor and the author of 24 books. His previous stories included Cambodia’s southern coast and Vietnamese Buddhism. He presently lives in Chiang Mai, Thailand.