Caskets in the shape of fish, tennis shoes and ice cream bars crafted by Accra carpenter Eric Kpakpo Adotey, who designs made-to-order fantasy coffins. Photo by Charles Cecil.

By Charles Cecil

People go to Ghana to see historic coastal slave castles. Others come to buy kente cloth for a colorful wall hanging. Reasonably priced tailors adept at creating stylish attire for special occasions attract travelers from Europe and the Americas. And then there are those to come to explore the roots of their African heritage.

All of these are excellent reasons for a trip to Ghana, but while there, try to find time to stop by a workshop or sales room offering “fantasy coffins.” Not that you actually need a casket. Consider the trip as a visit to a contemporary art gallery.

The use of fantasy coffins–called abebuu adekai, or “proverb boxes” in the Ga language–dates from the 1950s. The originator of this art form was a carpenter named Seth Kane Kwei. Kwei made a cacao-pod-shaped sedan chair for a tribal chief to use during a festival. Unfortunately, the chief died before the festival. He was buried in the cacao pod instead.

When Kwei’s grandmother passed away not long afterwards, he made an airplane-shaped coffin for her, since she had always wanted to fly but had never had the opportunity. When people saw these two coffins in their separate funeral processions, the idea caught on, and requests for others began to roll in. As requests increased, Kwei trained other artisans in the craft.

Kwei died in 1992, but his grandson, Eric Adjetey Anang, has carried on the work and has done much to promote coffin making as a folk art form that today is appreciated by collectors outside Ghana. Other Kwei apprentices have set up their own workshops. Today, there may be as many as a dozen workshops in the greater Accra area turning out fantasy coffins.

During my recent visit, I visited the workshop of Eric Kpakpo Adotey, who does business as “Erico.” Eric has been manufacturing coffins for twenty years in his workshop in Teshie, an eastern suburb of Accra.

Accra, Ghana. Erico Coffin Workshop, operated by Eric Kpakpo Adotey, Maker of Made-to-Order Fantasy Coffins. Photo by Charles Cecil

As I entered the workshop, the smell of sawdust and acrylic paint filled the air. Once fully assembled, the coffins are sanded several times to achieve a smooth surface free of any bumps or crevices before beginning the painting. I asked what the major considerations were in determining a coffin’s design and construction.

“Many Ghanaians regard death as a call to glory, a call to a higher level of service,” Eric responded. “Funerals are not so much a time for grieving as they are a time for celebration. The coffin design is seen as a vehicle both for remembering the departed and for speeding them on their way to the next level of existence. The family usually arrives with an idea of how they want their loved one to be remembered.”

“The only restrictions on design are that coffins in the shape of a lion, eagle, or elephant are reserved for the burial of chiefs,” Eric added. Such designs are only appropriate for people possessing significant power or who hold high positions of authority.

Ghana fantasy coffin maker Eric Kpakpo Adotey prefers to provide caskets shaped like lions only to burials for important chiefs. Photo by Charles Cecil

“The choice of wood is important,” explained Adotey. “When coffins are made for export (usually for display rather than actual interment), mahogany is used. It’s a harder wood, takes longer to carve, costs more, but is safer for shipping. Coffins made for actual interment in Ghana are usually made of African whitewood, which we call wawa. This is a softer wood and will decay in 8-10 years. Wawa has a fine texture and is a low-density wood that is easy to work with.”

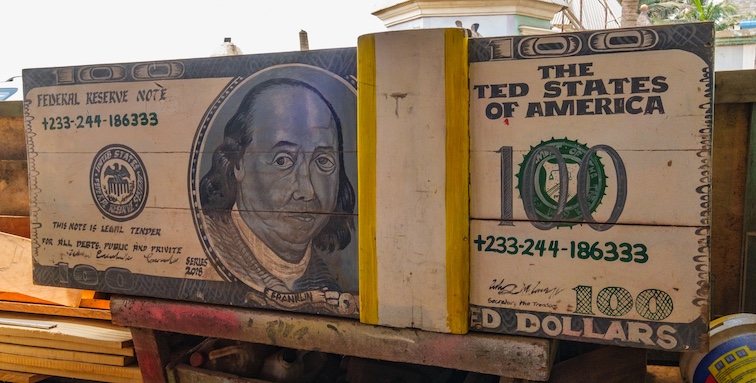

When the World Bank asked Adotey to make a box for display in the form of a U.S. hundred dollar bill, mahogany was used. Coffins made for local use can be purchased for the equivalent of as little as $600. Those for export will cost around $3,000, plus shipping.

Accra, Ghana coffin in the shape of a hundred-dollar bill produced by the Erico Coffin Workshop. Photo by Charles Cecil

Depending on the intricacy of the design, a coffin can be completed in 2-4 weeks. In Ghanaian culture, this is not an unusual time to wait before interment. If coffins are ordered in advance of a death, the buyer should have a sheltered storage space, since the coffin shouldn’t be exposed to the elements before its time to be used.

To meet the needs of some buyers, whose homes may not have a lot of extra space, Eric has designed a vertical-standing model of a popular Ghanaian beer. The cover opens easily, revealing shelves inside which can serve as storage space for toiletries, cooking ingredients, or other items that need to be kept nearby when not in use.

Accra Coffin maker Erick Kpakpo Adotey with a casket in the shape of a Beer Bottle. Shelves inside can be used for the storage of household items until the need for burial arises. Photo by Charles Cecil.

A number of finished examples of best-selling designs are on display in Eric’s workshop. Fish-shaped caskets are common since many Ghanaians earn their living as fishermen. You can be sure to see several examples if you stop for a visit.

The Ghanaian practice of being buried in a coffin representing the deceased’s profession, or hobby, or special interest transforms the somber act of burial into a celebration of life, using custom-made coffins that reflect the personality, status, career, or unfulfilled aspirations of the deceased. Posters announcing the passing of someone are often posted on walls for public display, announcing wakes or funeral timing and information.

Posters in memory of the recently deceased on display in Elmina, Ghana. Photo by Charles Cecil

In the last 10-15 years, Ghanaian coffin making has become internationally recognized as an African folk art form. One of the more successful practitioners of this art is Eric Adjetey Anang, Kane Kwei’s grandson. When Anang decided to promote his creations as works of art rather than fanciful but utilitarian burial boxes, he initially had difficulty finding appropriate facilities for display in central Accra. Eventually, Alliance Francaise and the Goethe Institute (institutions supported by the French and German governments to promote their national cultures) offered their facilities. This helped establish his reputation as an artist.

Anang made his first visit to the United States in 2011, where he was warmly welcomed by Ghanaian residents. “Nobody calls me a coffin maker or a carpenter,” he smiles. “They call me an artist. But I’m used to all those names.”

Anang has been chosen for residencies in Europe, Asia, Africa, and North America. Iowa State University hosted him for a five-day workshop in 2014 during which he built a coffin in the shape of an ear of corn. In 2019, he was chosen by the Madison, Wisconsin Arts Commission for a year’s residency. Madison provided him with access to a free private art studio, as well as a stipend and community programming opportunities.

The following year, he held a solo exhibition at the University of Arkansas’ Windgate Center for Art + Design in Little Rock. The exhibition’s title: Celebrating Death: Fantasy Coffins of Ghana.

His art is now displayed in museums and galleries throughout the world, including the Stanley Museum at the University of Iowa, the Chazen Museum of Art in Madison, Wisconsin, and the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada.

Fantasy coffin in the shape of a crab. Fishermen in Ghana like their caskets shaped like fish, except if their careers were spent catching squid or eels. Photo by Charles Cecil

Another well-known artist is Paa Joe (more formally, Joseph Tetteh Ashong), a nephew of Kane Kwei. After working for his uncle for twelve years, Joe established his own workshop, where he is assisted by his son Jacob. Joe’s work has received international attention, being included in exhibitions in Europe, Japan, and the USA. His fantasy coffins are in the collections and on permanent display in many art museums worldwide, including the British Museum in London, the Brooklyn Museum in New York, the Royal Ontario Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka.

Ashong’s workshop in Accra has been visited by former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan and former president Jimmy Carter. President Bill Clinton stopped by during an official visit in 1998. Recently, The Superhouse Gallery in New York City hosted an exhibit of Paa Joe’s work.

Adding such an unusual subject to your itinerary may seem counterintuitive, but it’s a particularly Ghanaian art form that you won’t find being created elsewhere, and it will definitely give you something to talk about when you return home. Any local travel and cultural analysis agent can arrange a visit to any of these gallery workshops. But as the above museum list indicates, you don’t have to go to Ghana to see fantasy coffins. The largest collection outside of Ghana is actually in Houston, Texas at the National Museum of Funeral History. “A Life Well Lived: Fantasy Coffins from Ghana” displays twelve carefully crafted coffins. Beginning in July 26, 2026, the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico, will host an eight-month exhibit of Ghanaian coffins featuring the work of five well-known coffin artists.

What began in Kane Kwei’s mind in the 1950s, an idea seeking a re-purposed use for a sedan chair built for a chief who died prematurely, is now well-established both as a cultural practice among the Ga people of southern Ghana and as an internationally recognized folk art form. It’s a great example of the lasting influence of one person’s imagination and creative skills!![]()

Charles Cecil is a U.S. ambassador turned photographer who spent much of his career in Africa. His most recent stories for EWNS have described the Wadis of Oman and Spain’s Camino de Santiago.