Though silent for thousands of years, Petra’s stone buildings still tell their stories to around one million visitors a year. Photo by Ramaa Reddy

There are few places in the world that inspire ‘awe,’ an emotion experienced when we encounter something so vast that our sense of self recedes. Petra is such a place, a desert entrepôt dating back more than three millennia that leaves visitors filled with amazement, wonder and humility.

Petra lies in southern Jordan, in Wadi Musa, which is around a three-hour journey by car from Amman on the King’s Highway, an ancient thoroughfare that once connected Biblical kingdoms and today links Jordan’s historical sites.

The Monastery

I visited Petra recently entering through Little Petra, a gateway community of small shops and caravanserais built in the first century AD. It is widely regarded as Petra’s backdoor, but it is the most efficient way to arrive and has the benefit of being next to the Ad-Deir Monastery, an iconic structure built in the 3rd century BC. Carved directly into the rock face, the Monastery, the largest structure in Petra, is Nabataean in architecture with Hellenistic Corinthian columns and a Mesopotamian entryway. Archeologists say it was used as a church in Byzantine times.

The Monastery is one of the most imposing buildings. To get there from the valley floor you can hike up a steep path or pay $15 to ride a Bedouin’s donkey. Photo by Ramaa Reddy

The 8 km walk from Little Petra to Petra leads to Wadi Musa, which also is known as the Valley of Moses since it is here the Israelite leader supposedly struck a rock with his staff and water gushed forth. Before beginning the trek be sure to stop for refreshment at the lovely shaded tea shop close to the Monastery that offers a nice view of the whole area.

Most people, however, enter Petra through its front door in the east, which consists of a winding gorge some 1.2 km long called the Sik. Bordered by dramatic, overhanging cliffs, the fissure was formed by the grating of two tectonic plates, the Arabian and the Palestine-Sinai Sub-Plate. The inexorable pressures caused rock formations and the intermingling of brick-red, coal-black, russet and cobalt hues of the sandstone cliffs. Along the walk are reliefs, created around 100 BC of camels used by the caravans entering Petra.

Preview of coming attractions. A walk through the Sik is the perfect preparation for a day in Petra. Note the water course hewn into the rock. Nabatean society flourished because of its ability to locate and transport water. Photo by Ramaa Reddy

In the movie, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Harrison Ford in his hunt for the Holy Grail remarks that it is located at the end of a narrow gorge called the “canyon of the crescent moon.” Hollywood is not the only entity fascinated with this locale for its beauty and history; For centuries people have traversed this walk by foot on camels or carts to be rewarded by a magnificent façade of Al-Khazneh or the Treasury.

The Treasury

Carved into a red sandstone rock face, the Treasury is Petra’s most ornate and well-preserved structure. Constructed in the first century BC by Aretas III Philhellene, it is a fusion of the Hellenistic and Middle Eastern worlds and is decorated with Corinthian columns and lion friezes. Isis, the Egyptian goddess, is depicted in the center while on the ground level are sculptures of Zeus’s sons. Inside the treasury is a square chamber that is believed to be the mausoleum of Nabataean king Aretas IV. Another legend says it once contained the treasure of a Pharaoh.

The Treasury is the most iconic building in Petra. It is the first site visitors see when they emerge from the narrow Sik. Some people get out sketchbooks and begin to draw. Others simply stand in mute contemplation. Was the building 2,000 years ago a bank, mausoleum or government office? Nobody knows for sure. Photo by Ramaa Reddy

The Treasury can get very crowded during the day so try to visit either early or late. It takes at least a day to fully explore Petra so it’s good to have an agenda. About 905,000 tourists visited Petra in 2022 according to the Jordan Times; In 1985, Petra was listed a UNESCO World Heritage site and in 2007 it joined the Great Wall of China and the Taj Mahal as one of the Seven New Wonders of the World.

Ancient Yet Timeless

One 19th-century English biblical scholar called Petra a “rose-red city half as old as Time.” The description is apt since a morning stroll through the ruins will take the visitor past Roman baths, a nymphaeum grotto, several ancient temples and the remains of a Byzantine church. Look one way and there’s a 13th century Crusader fort. Turn the other direction and you’ll see a Hellenistic-styled amphitheater built in the first century AD that could accommodate 4,000 spectators after it was rebuilt by the Romans.

The Nabataeans

Being at the center of commercial trade traffic, the Nabataeans started out as caravanserais – providing food, water and fresh camels for travelers. Later, they became skillful traders dealing in frankincense and myrrh – a gum resin collected from south Arabian trees. They also got salt and bitumen from the Dead Sea that they exported to Egypt for the purpose of mummification, medicines, and insulating seafaring ships. In time, they established trade centers in Arabia, Mesopotamia, Persia and Greece, the Aegean islands, Italy and the Horn of Africa, and became an economic power. They adopted elements from all these cultures while keeping their own Arabian roots and motifs like rosettes, pinecones and pomegranates which one can see gracing many columns.

They defended their land against the Seleucid Empire, the Egyptians and Greeks until they finally were annexed by the Romans in 106 AD. Under Nabataean rule, Petra became the hub for a spice trade that extended far into India and China. The population soared to 25,000. But in 551 AD the city was damaged by an earthquake and almost all the people moved away.

For millennia, Petra was hidden from the world and inhabited only by the Bedouins who kept its whereabouts a secret until 1812 when John Lewis Burckhardt, a Swiss explorer, rediscovered the hollow tombs cut into Petra’s red rock cliffs.

How could a pluralistic society that withstood the onslaught on empires and established trade routes across the Mediterranean, throughout the Middle East and into Asia suddenly disappear? These questions wash over visitors as they stand transfixed in front of the Treasury’s muted grandeur.

Skilled Hydraulic Engineers

Nabataeans chose Petra as the location for their capital as it was ideally protected by hills and mountains and endowed with a vital commodity – water. They learned from settled communities in the area how to capture water and divert it into cisterns. By the 2nd century AD, they became skilled hydraulic engineers who controlled flooding and used angled clay pipes and gravity to send water from springs at elevations as high as 4,350 ft to irrigate terraced agriculture.

Archaeologists have recorded 200 water storage installations at Petra creating a total capacity of 40 million liters – enough to quench the thirst of 100,000 inhabitants! During the Roman period, the wealthy had their own private bath heating system which was sometimes used to heat chambers in the winter.

The Royal Tombs, built around 70 AD, are adjacent to the theater and have magnificent facades. Sculpted into the cliffs, most tombs in Petra served as burial chambers. The Silk tomb has swirls of colored sandstone and a dramatic colorful ceiling while the Urn tomb derived its name from the jar that crowns the pediment is built high on the mountainside and requires a climb. The tomb is headed by a deep courtyard with colonnades on two sides and high up in the façade are niches that open into small burial chambers. In 446 AD the tomb was adapted to serve as a Byzantine church. The Corinthian Tomb, like the Treasury, contains both Nabataean and classical architecture styles.

In one Petra burial chamber, dating to 1,500 BC in Rumi-al-Mataha, archaeologists found the skeleton of a male hunter, probably in his 40’s, buried face down with arms and legs tied. In his forehead was an oval hole. He was buried with his belongings to show Nabateans believed in an afterlife. In the Palace Tomb, dated to the 2nd century AD, remnants of a water reservoir are visible. It has a grandiose five-story façade and was probably used as a banquet hall or funerary.

Bedouins today use some of these tombs to serve tea and mingle with tourists.

Historically, Bedouins are nomadic herdsmen. But today they identify more as Jordanian citizens. Many Bedouins living around Wadi Musa and Wadi Rum speak English and are generous with their hospitality. Photo by Ramaa Reddy

After those tombs, the next stop is yet another tomb, the Ad-Deir or the Monastery. The walk involves climbing around 800 steep steps and I would recommend hiring a donkey from the Bedouins for around $15 one-way. The walk is spectacular, with unusual sandstone formations interspersed with Juniper, acacia, evergreen oak trees and sundry shrubs, which are often used by the Bedouins for fuel, wood, fodder, and tent construction.

The Bedouin Tribe

Throughout Petra’s 12 miles of trails there are many Bedouin kiosks selling trinkets, scarves, and small carpets. Those who are less entrepreneurial remain desert herders who take animals into desert areas like Wadi Rum in winter and return in March to the grassy plateau.

The Jordanian government provides permanent housing for Bedouins outside Petra, but many remain endogamous and live in large male-dominated tribes. In Bedouin culture, if a person kills or harms another clansman, his related family will have to pay blood money to the injured clan.

Bedouins generally spend the day caring for livestock while the women cook and produce milk products like butter and yogurt. The women also weave rugs and make tents from goat hair and wool.

Dapper Bedouin men take pride in their appearance. Many line their eyes with Kohl, a cosmetic made from coal, olive oil and herbs. Solo female tourists have been known to have dalliances with Bedouin men. After marrying a Bedouin, one New Zealand nurse named Marguerite van Geldermalsen recounted the experience in her book, ‘Married to a Bedouin’.

Young Bedouin men relax and refresh by drinking hot tea at a cafe near Little Petra. Photo by Ramaa Reddy

The Bedouin Way of Life

While in Jordan, one has to experience a night gathered around a campfire under the stars. A good place to do this is at the Little Petra Bedouin Camp which is close to Little Petra and just a 12-minute drive to the Petra Visitors Center and Museum. Owned by a Bedouin family, the camp consists of an array of tents each fully stocked with modern amenities. The restaurant serves a daily lunch and dinner buffet where local Bedouin women make Za’atar Man’ouche, a flatbread filled with thyme and olive oil. The lounge area, which opens after dinner, offers entertainment and endless cups of mint tea you can enjoy while listening to Bedouin musicians play the oud, a traditional stringed instrument that resembles a pregnant guitar.

Wadi Rum

From Petra I traveled to Wadi Rum, a magical ochre desert landscape known for its towering buttes and sandstone arches. The desert here is enticing not just for its unique iron oxide concentration but for its pivotal history. It is here that British officer T. E. Lawrence and Prince Faisal bin Al-Hussain, led the Arab revolt (1916-1918) against the Ottoman Turks.

After the First World War, Britain’s Arab allies hoped to achieve independence. In his book Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Lawrence wrote that he fought on the side of Arabs who ‘grew accustomed to believing me and to think my government” like myself, sincere,” but he says “it was evident from the beginning if we won the war these promises would be dead paper.”

Bedouin excursions between Petra and Wadi Rum usually are taken atop a camel. Some of the trips include an overnight stay in the desert and a Zarb dinner.. Photo by Ramaa Reddy.

Lawrence spent time in the desert and described it as “vast, echoing and God-like.” Upon entering Wadi Run, one faces a large striking rock formation named the Seven Pillars of Wisdom after Lawrence’s book. There is also a Lawrence Spring.

Nabataean Inscriptions

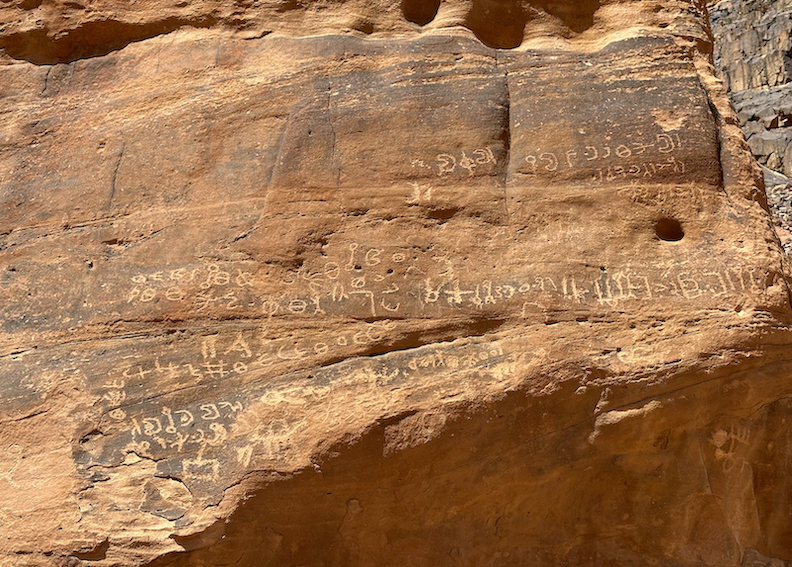

Around Wadi Rum are dunes with petroglyphs and inscriptions that date back more than 4,000 years. There are drawings of camels and Ibex as well as human figures. Some of the inscriptions are in Nabatean script, which was written from left to right. Around 6,000 of these chiseled in stone inscriptions have been located around Jordan and Saudi Arabia. Most were simple greetings, not literary or philosophical epigrams. After the conquest of Alexander the Great in the late 4th century BC, Greek became the official language in Petra which was later replaced by Arabic in AD 700.

The camel-mounted warriors of Nabataea were so skilled that they brutally slayed nearly 4,600 Greek soldiers during a single battle in 312 B.C. Nabataean merchants held a monopoly on Silk Road trade at the crossroads of Africa, Europe and Asia for hundreds of years. And Nabataean porters had secret reservoirs of water and supplies that only they could find. Then, in A.D. 106, Petra was folded into the Roman Empire and the great civilization of Nabataea came to an end. Many of its buildings remain. So, too, does Nabatean graffiti like these lines scrawled on the cliffs near Wadi Rum. Preserved by the dry desert environment, the writing survives but nobody knows what it says. Photo by Ramaa Reddy.

At an elevation of 6,083-ft., Jebel Um Ad Dami is the highest bluff in Wadi Rum. Many travelers opt to climb it; others take long walks to soak in the desert’s vast expanse. If staying overnight in a Bedouin camp, be sure to try the local specialty called Zarb. It’s a Bedouin dish cooked underground with rice, chicken and vegetables.

Petra’s fascination today lies not in its association with Indiana Jones but with lingering echoes of the Nabatean civilization that softly murmur at the end of the day when shadows envelop the terraced caves wealthy merchants once called home.![]()

Ramaa Reddy is a Columbia School of Journalism graduate whose work has appeared in the Miami Herald and the BBC. Her food and travel articles can be found in the digital magazine, venturetraveller.com.